Unless you were abducted by aliens, and just returned to Earth after being their lab rat human for several months, you’d know that Turkey is going through a major economic crisis. The lira dollar exchange rate, which was 4 at the end of April, has “stabilised” around 6 after hitting 7 earlier last week. The stock market index, in dollar terms, and benchmark bond interest rates are at levels unseen since the 2008 global crisis.

So what exactly happened? Who is to blame? What are the consequences of the asset meltdown? How is the government responding to the situation? Is there a way out for Turkey? Can the Turkish crisis spread to other emerging markets (EMs)? Luckily, your friendly neighbourhood economist has donned his swim cap and goggles (sorry, I couldn’t afford a superhero costume from Amazon at the current exchange rate) to entangle this Shakespearian economic tragedy for you – with a little help from the Bard.

Something is rotten in the state of Denmark Turkey (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 1)

Something (actually many things) has been rotten in the state of Turkey for a while. On the face of it, this is an economy that has been maintained solely by external financing for quite a while. Obtaining this financing was not an issue at all – not only before the global crisis, when liquidity was plenty but afterwards as well, as central banks flushed the world with cheap money, some of which, in search for higher yield, found its way to EMs like Turkey. Unfortunately, most of this cash was not channelled into productive activities that would increase the country’s exports, but to consumption and construction. In other words, Turks were living beyond their means.

The Federal Reserve (Fed), the Central Bank of the United States (U.S.), recently started unwinding its balance sheet, i.e. pulling back this money. As a result, many EMs have been experiencing capital outflows, and the dollar has been gaining against all significant EM currencies. The countries most dependent on external financing, and those with the most exposed economic positions have been hit the worst. Turkey has stood among the EM pack as one of the most vulnerable. For example, its external financing requirement is over $200 billion, and its credit boom was second only to China’s. So even without all the “negative newsflow”, I explain below, Turkey would still have been one of the most affected countries from the Fed’s balance sheet normalisation, if not the most.

Now is the winter of our discontent, made glorious summer by this sun of York Kasimpasa. (Richard III Act 1, Scene 1)

Bearing that in mind, certain events over the last three months first triggered, and then deepened the Turkish crisis, thanks to Supreme Leader Admiral General President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who was born and raised in the working class Kasimpasa neighbourhood of Istanbul. Lira’s (and more generally Turkish assets’) troubles started back in May, when, during a visit to London, Erdogan irked investors with his unconventional views on the relationship between interest rates and inflation and central bank independence. Then, he sowed the second wave of suspicion when he put his son-in-law Berat Albayrak in charge of the economy. Finally, the U.S. sanctions that followed when he refused to release evangelical preacher Andrew Brunson, who is being tried for (unfounded) charges that he took part in the 2016 putsch, put the nail on the coffin.

Erdogan’s response to the crisis has been less than ideal, to say the least. Not only did he escalate the row with the U.S. with daily aggressive language towards that country, but he also has prevented the Central Bank of Turkey hike rates significantly until now – more on that below. He wasn’t accurate in his remarks, either: For example, he stated that if the U.S. had dollars, Turkey had God – but dollar bills have the inscription “In God we trust” on them, so Americans have both dollars and God, it seems…

Neither a borrower nor a lender be; for loan oft loses both itself and friend (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 3)

So what are the consequences of the meltdown in Turkish assets?

For one thing, inflation has skyrocketed. Annual inflation was 15.9 per cent in July, before the lira’s collapse began, and it could hit 20 per cent in the next couple of months, once the depreciation takes its full toll on prices.

However, the real elephant in the room is Turkish companies’ huge foreign currency (FX) debt, mainly to Turkish banks. Even before the lira’s freefall, a few large conglomerates had already asked (and secured) to restructure their debts. Of the companies with FX debt, the ones with revenues in liras will have a tough time making their payments even if they do not default. Even businesses without FX debt would suffer: It is impossible to secure any loans below interest rates of 30 percent or so at the moment, so firms need to forget about new investment or working capital per cent..

To make matters worse, the excessive volatility of the lira, which has accompanied the currency’s depreciation, has brought economic activity to a sharp slowdown. Anyone who has anything to do with the exchange rate is opting to “wait and see” rather than lose money because of the wild exchange rate swings. The high interest rates are taking their toll on the economy as well, and Turkey is headed straight into a recession.

With economic activity in such dire straits, it is not difficult to predict that many people will find themselves without jobs in the next few months. Real wages will suffer as well, and given the country’s import dependence, even for many domestically-produced goods that use imported intermediate goods, Turks’ buying power will diminish significantly. In fact, Erdogan did not need to call for a boycott of iPhones: Even before the crisis, Turkey had one of the highest iPhone prices, thanks to excessive tariffs, but now, most Turks will not be able to afford one at all.

A horse rate hike, a horse rate hike, my kingdom for a horse rate hike (Richard III Act 5, Scene 4)

The government and Erdogan’s initial response to the crisis was completely off the track. Rather than tackle the crisis with economic measures, they got engaged with a tit-for-tat fight with the U.S. and President Donald Trump. While it could be understandable, with the looming local elections, for Erdogan to shift the blame to the U.S., the inaction only exacerbated the problem – and his sharp daily rhetoric towards the U.S. irked investors further.

Their response was remarkably better over the last week. First of all, while the Central Bank tightened liquidity through some backdoor steps, the banking regulator made it remarkably more difficult to short the lira. At a conference call with investors on August 16, Berat Albayrak generally said the right things. As a result, the dollar-lira exchange rate fell somewhat, and was about to end the week at 5.6-5.8, before Trump’s latest threats of sanctions (again, over Twitter), raised it to above 6 again.

However, the government and Erdogan have failed to take any “real and direct steps” that would permanently calm markets. For one thing, Turkey needs to free Brunson; it is as simple as that. On the economic side, tight monetary (higher interest rates) and fiscal (spending cuts) policies should be accompanied by a well-designed mechanism to deal with bankrupt firms. Unless these steps are taken, any respite in Turkish assets will only be temporary. During his conference call, Albayrak underlined fiscal restraint, but stopped short of promising rate hikes – he would have to face his father-in-law’s wrath if he did so. And he claimed that banks were sound, ignoring the imminent sharp rise in non-performing loans, and was numb about corporates.

In fact, rating agency Fitch said on August 16 that “incomplete policy response” to the recent fall in the lira was unlikely on its own to stabilise the currency and economy for a significant period, and that a greater effort needed to be made. Both Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s downgraded Turkey’s sovereign ratings on August 17, citing similar concerns. Echoing parallel thoughts, economist and investment guru Mohamed El-Erian emphasised on the same day that Turkey would not be able to rewrite crisis management rules.

Hell itself breathes out contagion to this world (Hamlet Act 3, Scene 2)

It is one thing if Turkey sinks on its own, but it’d be an entirely different matter if it dragged several emerging markets, and even some developed ones, down under as well. The consensus sees this risk of contagion to be very low: Turkey makes up a tinyl part of world GDP; it is not the primary trading parent of any country, save a couple of Balkan states no one can show on the map anyway, and only a couple of Club Med (Spanish and Italian) banks are exposed to the Turkish financial system.

This argument, however, ignores two crucial points. For one thing, as El-Erian notes in the article I mentioned above as well, EMs have resolved similar crises in the past by applying traditional tools”: “Opting for interest-rate hikes and an external funding anchor to support domestic policy adjustments.” Both are out of the table at the moment because of Erdogan’s distaste for both. In fact, Albayrak clearly ruled out seeking help from the International Monetary Fund during his conference call, and Qatar’s $15 billion would not act as an anchor at all. I would love to be proven wrong, but Erdogan would not resort to either higher rates or the Fund unless he is convinced there is absolutely no other way – and by then, it would probably already be too late.

Moreover, the U.S., through its Treasury, has helped countries in crises in the past. However, this time around, they are actually exacerbating the crisis, let alone help Turkey out. For example, only hours after Albayrak told over 6,000 investors that he did not expect a fine to state bank Halkbank for busting Iranian sanctions, the U.S. Treasury Secretary with the unspellable and unpronounceable name announced that more sanctions were ready.

To sum up, in normal times, the Turkish crisis would have been self-contained – and resolved pretty rapidly. However, thanks to Erdogan and Trump, we are not living in normal times, and there is a good chance that the Turkish currency crisis will drag on for a while before turning into a full-blown economic collapse and spill onto at least the weakest and most vulnerable of the EM pack.

It is time we close the curtains on our Shakespearian economic tragedy. I’ll leave it to the Bard:

For never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet Turkey and her Romeo Erdogan. (Romeo and Juliet Act 5, Scene 3)

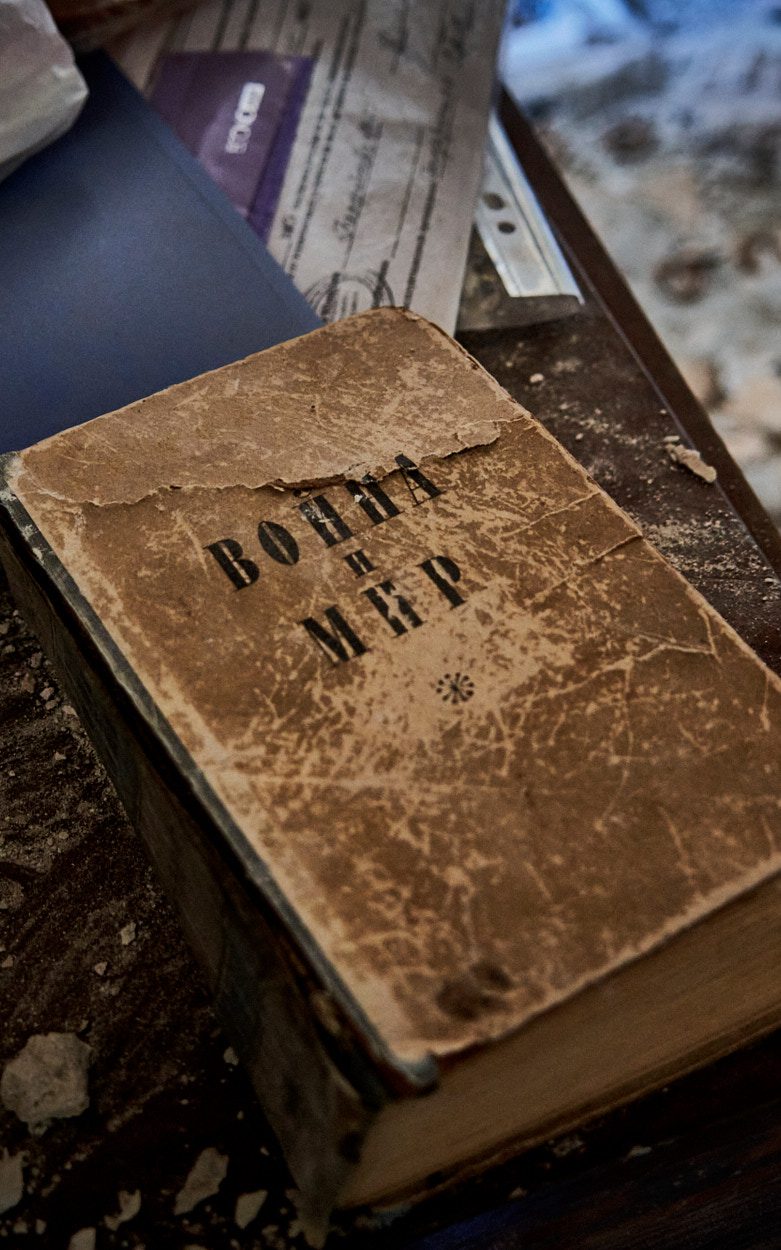

Photo Caption: President Erdogan said if the U.S. has dollars, Turkey has God. Dollar bills prove him mistaken.