Until a few years ago the question of whether Belarusian brands might take advantage of political events in their advertising would be considered hypothetical, or even awkward. But 2020 came and quickly changed everything. First of all, the demonstrations in Belarus grew to a mass scale compared to previous protests. Second, those same protests emerged not only as political and social phenomena but also influenced the fields of marketing and advertising.

The country remains stretched between two parallel realities: On the one hand, the punitive administration keeps running, everything that is supposed to be allowed is still forbidden. But the situation is reflected in the creative arts. People do not want to yield to the conditions in which they are forced to exist, and the political situation is not just impelling them to be more united but also influencing the way they buy products and services.

The market situation itself has changed with the help of smartphones, social media, viral videos, and memes. Alternative sources of information such as Telegram have emerged. As in Hong Kong, the protests in Belarus became a strong promotional incentive for this messaging app. Pavel Durov, the founder of Telegram, supports the protesters – the application was quickly translated into Belarusian, and the official national flag was replaced with the white-red-white flag – and this encouraged people of different ages, social classes, and education to use the app, which in time also attracted pro-government trolls, propagandists, and bots. Moreover, Belarusians learned to use proxy servers and anonymizers more than ever before.

Anyone can become a blogger, videographer, author of sensational content. Anyone can create a visual or text-based punchline. Piracy became widely accepted. Photographers don’t worry if their photographs are reposted numerous times, graffiti is turned into stencils that gain lives of their own even if public servants quickly paint it over.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

When a revolution is happening, there’s not always the space to explain the details of intellectual property. Paintings, stencils, stickers are widely available, photographs and recordings are used to make posters and video clips. The famous mural of the “Change DJs” (two DJs who turned an official celebration into a rally for opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya when they queued the song by the Soviet pop star Viktor Choi that became an unofficial protest anthem) was painted on “Change Square” byRaman Bondarenka before his death, but the author of the original artwork is Dzmitry Dzmitryjeu.

Most importantly, the way people think has changed. Big and small brands began to demonstrate political awareness and solidarity and understood that this influences their sales numbers. The software engineering company EPAM publicly supported its arrested employeesand their families. Many small companies did not mark down the names of arrested workers as absent without permission.

Memes – From Graffiti to Advertising

Three percent – according to one unofficial poll, this was the actual level of support for Alyaksandr Lukashenka in the disputed August presidential election.Pushback spread to all levels of society just like the pandemic, regardless of age or social status. Even the self-proclaimed president publicly commented on the nickname bestowed on him by the people: “three percenter.”

“3%” graffiti can be seen on the Tabakerka tobacco and ticket kiosks, a chain supposedly owned by a member of Lukashenka’s family or one of his associates.

The symbolic “3%” also pushed its way into commercial advertising; it became the most popular discount, a call sign for the growing number of protest supporters. More than just a promise of value, it’s a new kind of club card.

Another image meme is that of a woman in a painting. The authorities confiscated Chaim Soutine’s Eva, owned by Belgazprombank, as part of an investigation into the bank headed by Viktar Babaryka, former presidential candidate and currently a political prisoner. This inspired the coinage “Evalution” (Eva + Revolution), which soon landed not only on t-shirts, sweatshirts, and stickers but also in ads for the broadly respected Center for Reproductive Health.

Even a brand connected to the current government – the market-leading lingerie and clothing manufacturer Mark Formelle – went so far as to run an ad playing on a strange film with Lukashenka, where the politician asks a reporter, “Can you see the virus? I can’t.” The leading role in the ad is played by Dzmitry Kakhno, a popular wedding and party emcee who was sentenced to 10 days in jail but held two days longer.

Another interesting aspect of the peculiar autonomy in advertising is that after restaurants, pubs, bakeries, clubs, went on strike on 26 October, in answer to Tsikhanouskaya’s call, posters with disgraced heroes such as Kakhno, the Thai boxing world champion Vital Hurkou, and the famous gymnast Melitina Staniouta (who addressed some harsh words to the authorities regarding the situation in the country), were still up in shopping malls and in the metro.

The government’s actions influenced shopping behavior in Belarus in ways they could not have expected. It all started with the Symbal.by store. It was the first store to sell t-shirts that displayed the traditional Belarusian red-and-white embroidery on a t-shirt as a simple and cheap way (real embroidery is quite expensive) to make a political statement.

As time passed the store broadened its offer to all sorts of “ethnic” and white-red-white products and flags. When the sanitary authority and the rescue services decided the store should be closed for health reasons, customers lined up and bought up all its merchandise.

People Became Icons

And not just politicians, but ordinary people. A taxi driver who picked up a young guy who was being chased by the OMON riot police became the best ad for Yandex-Taxi in the history of the brand in Belarus; other people who gained significant popularity included one who ran along with a crowd of police waving a white-red-white flag, and of course, Nina Bahinskaya, an ardent fighter, who spent her life opposing the system with her iconic “I’m just out for a walk.”

And then there is Siarhei “Troublesome Business” Mironau, who enchanted everyone with his ability to subtly troll the national television channel (journalists who could not grasp all his loaded statements and subtexts gave him airtime) and familiarized people with many memes that soon became popular.

The young factory worker was arrested during one of the protests announced by Tsikhanouskaya for 26 October. Journalists from the national television recorded an interview with him at a police station. By the way, this is a popular technique used by the pro-Lukashenka media: here’s a protester, let’s ask him some weird questions. But Mironau would not be provoked. Even as he sat in jail, his words appeared in the language of the streets and on stickers, t-shirts, and all sorts of surfaces. “Troublesome business”, his euphemism for the strike, became particularly popular. A cafe in Minsk started brewing coffee under this name. On his Instagram page, former Belarusian national football team player Vitaliy Kutuzov said he expected Siarhei to gift him a pair of limited-edition famous-brand sneakers (in his interview Siarhei said he intended to take up serious running, interpreted as a reference to the marches and escaping the police).

The Comeback of the White-Red-White Flag

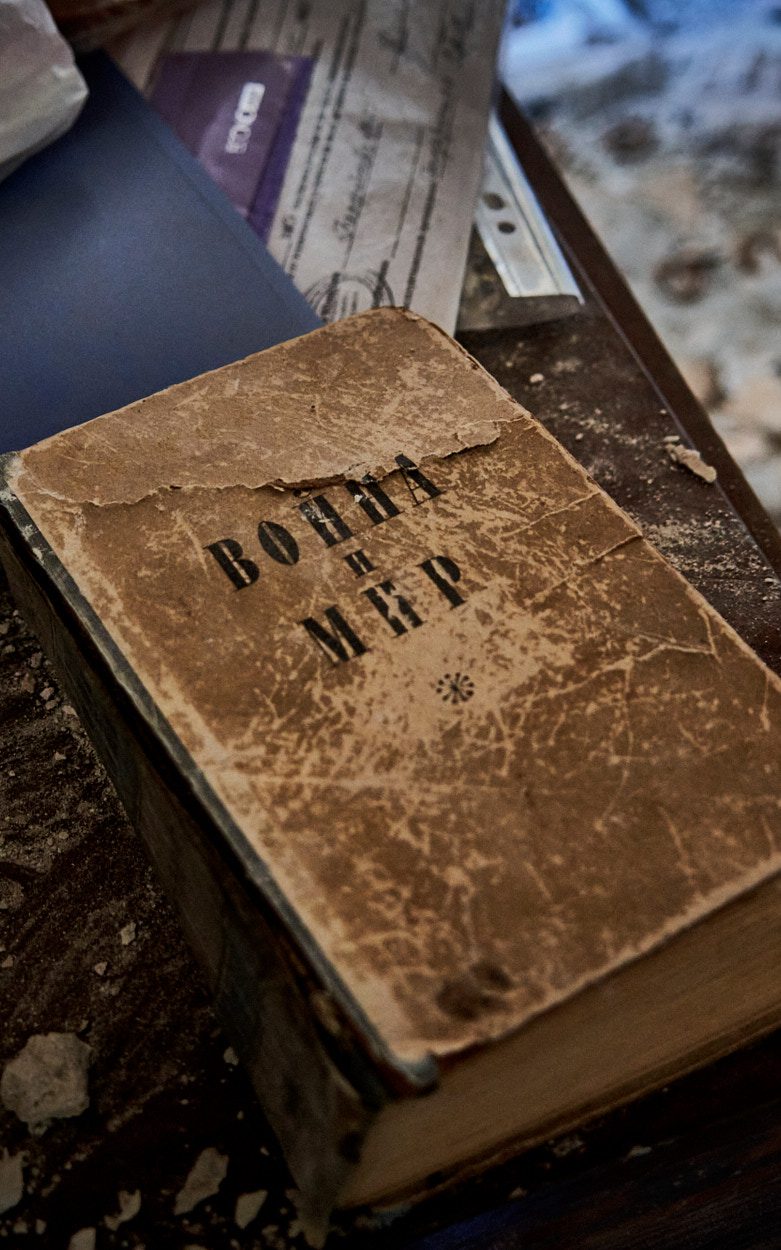

It is hard to say how much sales rose of the red lipstick that is the invariant attribute of opposition leader Maria Kalesnikava or how many women had their hair restyled or bought white suits after Tsikhanouskaya changed her image. Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses flew out of bookstores after Babaryka recommended it in an interview; white-and-red fabric was sold to the last meter; red-and-white pastila became a hit; Koton, a Turkish store in one of the biggest shopping malls in the city center, presented a collection of all red-and-white garments; and AliExpress started selling white-red-white products sporting the Pahonia – the coat of arms of the Belarusian People’s Republic of 1918, later the national symbol from 1991 to 1995, and still a symbol of the opposition.

The incredible popularity of white-red-white symbols is more astounding when you consider the results of a public opinion survey conducted just before the disputed August presidential election as part of the “Let’s be Belarusian” campaign to popularize Belarusian culture and language.

The researchers concluded there was slight chance of white-red-white emblems becoming the national symbol. They surmised the most likely choice was the European bison, the animal which proudly looks down from roadside monuments as a symbol of masculine power.

In the first days of the protests, I spoke to a few friends from the marketing profession. They pooh-poohed my conviction that the white-red-white flag would become the symbol of the protests: “No way, the workers will never walk bearing this flag.” Not a month later, MAZ autoworkers took to the streets carrying the white-red-white flag.

In this way, Belarus, like Hong Kong earlier, where protesters created large collections of photographs for journalists worldwide, cognizant of how important it is to present a beautiful, attractive, charismatic image of protests, confirmed the rule of aesthetics. The white-red-white flag triumphs not only because of its history, but also thanks to its beauty, aesthetic qualities, and the possibility to place it on nearly any given object, from clothes, walls, and candy, to flags of different districts (another interesting feature of the Belarusian protests: neighbors get to know one another and districts unite).

The New Belarusian Brand

A series of photographs from the women’s protests (when I was detained), in glossy magazine style, spread around the world.

The explosive mixture of soul-stirring documentation of people getting beaten, expressed in the aesthetic of professional photography, where angle, lighting, and symbolism play significant roles, and images which relate to global culture, Christian traditions, nearly dance-like gestures expressive of beauty, suffering, and strength – all this created the most incredible marketing product to emerge from the protests: a new image of the Belarusian people, which shocked not only their near but also their further neighbors, as much as it did Belarusians themselves.

The widely shared photo of shoeless protesters standing on a bench became the best social advertising, because it proved that it was the police, not the protesters, who broke windows and destroyed private property. Belarusians started calling themselves “amazing” (a term made popular by Maria Kalesnikava). The faces of revolution and its symbols changed like a kaleidoscope: from Tsikhanouski to Tsikhanouskaya, to Babaryka, Kalesnikava, and Pavel Latushka, to the Change DJs, to Raman Bondarenka, and Belarusians are surprised and encouraged by this image they have created themselves. They don’t want it destroyed.

The world considered them “moderate” for long enough, and now Belarusians are showing their “decisive” and “rebellious” faces. The attention attracted by the protests proved that people have some healthy vanity, they like being amazing, exceptional, and surprising.

The words written over a hundred years ago by the classical Belarusian author Yanka Kupala, whom we all have known since youth, have only now become a great advertising slogan for this country: “To be called human.”