Rehab in

Yerevan

By Lola García-Ajofrín

November 2022 marks two years of the ceasefire of the 44-days war between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

In Armenia, a country of just 3 million people, where military conscription is imposed on all young men, two recent bloody conflicts have given an exorbitant percentage of war veterans among its new generation of men.

Some 1,000 Armenian soldiers have been classified into various categories of disability. The invisible wound, the trauma, affects thousands of young men, no one knows exactly how many.

How is Armenia healing its new generation of men?

Visible

Wounds

Yerevan, ARMENIA - Hayk Khachatryan, a coach in a blue uniform, carefully pushes the wheelchair of a twenty-something young man in a green T-shirt towards an exercise bench in a bright gym room.

After the morning rain in Yerevan, the sun's rays filter through the window.

The convalescent in a wheelchair is holding a rubber medicine ball in both hands. Khachatryan, the coach, puts his hands on his shoulders, and the young man makes an effort to lift the ball right above his head. He lifts the ball and lowers it several times. The coach encourages him to do it one more time. The patient finally achieves it.

Khachatryan is an Armenian kinesiologist working at the Zinvori Tun (“Soldier's Home” in the Armenian language), a rehabilitation centre in Yerevan, established between an NGO, the Yerevan State Medical University and Armenia’s Ministry of Defence to treat soldiers.

The young man trying to raise and lower the ball is one of 300 veterans of the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war who are receiving treatment at this centre in Yerevan.

Armenia and Azerbaijan, two former Soviet republics, have been engaged in a dispute over Nagorno Karabakh since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Nagorno Karabakh is a mountainous enclave in the South Caucasus, populated by ethnically Armenian and geographically located within Azerbaijan. During the Soviet era, it had an autonomous status within Azerbaijan.

The long-running conflict has seen two major outbreaks of war.

Since then, both countries have accused each other of frequent violations of the ceasefire.

There was also a four days outbreak in April 2016 in which 350 people were killed.

While we were working on this article, a new round of violence spread on the night of September 12th to 13th 2022, as Azerbaijan carried out a wide-scale attack against Armenia, targeting some towns, including houses in Sotk, Goris and Jermuk. It continued until September 14th. As a result, more than 2,500 civilians were temporarily displaced and over 200 soldiers from both sides were killed in the worst fighting since the 2020 war.

Those who fought the first war are now young men between thirty-something and forty years old; those who fought the second war are barely 20 years old.

“My biggest challenge probably has been treating the boys from the last war,” Khachatryan explains with a sigh. He started to work at this centre in 2019, “firstly as a volunteer, after graduating from the Institute of Sport”, and soon, “all these kids from the war began to arrive”, he adds. They were young people between 18 and 20 years old, who were doing their compulsory military service when the conflict broke out.

Khachatryan says that after the war, “most issues were related to orthopaedic stuff. And also, spinal injuries were very common too.” “We have been trying to achieve maximum success in a very short time. And trust me – it worked. We did what seemed impossible,” he adds.

However, the patient who has marked him the most “probably has been my very first patient, who was able to start walking again in two or three months," he says. “He had botulism.”

Currently, at the Soldier House there is a staff of 30 workers, “and here, people don’t work only for money,” Khachatryan concludes.

One of the young men who were doing compulsory military service when the war broke out in 2020 is Alek Simonyan, 20, who sports a thick dark beard and a shy look today. He is currently receiving treatment at the Zinvori Tun centre in Yerevan.

Alek was just 19 years old at the time the conflict broke out. Armenia imposes mandatory military conscription for two years for all male citizens aged 18 to 27.

“It was Sunday and we were sleeping when the war started”, Alek recalls. "An explosion of a projectile woke us up, and we had a roll-call and went to the border."Before the war, he had studied at a vocational training institute for a few months, ”then I went to serve in the army.”

Now, it is time to start over again. Alek doesn't know yet if he will continue his education. “First of all I want to heal. Then I will start thinking about these things.”

1,000 young men suffered disabilities during the fights

Alek is one of some 1,000 Armenian soldiers classified into various categories of disability after the 44 days of the war in 2020. Among them, nearly 500 young men received serious injuries and about 120 are in need of prosthetics, according to the Armenian government.

In addition, about 7,000 soldiers were killed or missing in six weeks of war (3,900 Armenian and 2,900 Azerbaijani), according to the Council of Europe. It means nearly three times more than all the US soldiers killed in Afghanistan over 20 years.

“My parents didn’t know that we were going there,” says Ishaan Aslanyan, 33, a war veteran and Barcelona football club supporter, who walks with a crutch after several surgeries. He also receives treatment at the Zinvori Tun (Soldier's Home) in Yerevan. “Doctors saved my leg”, he clarifies. “They, let’s say, put everything together again,” he explains.

Aslanyan, who started to serve in the army when he was 20 years old and had served for 12 years when the war broke out, remembers that he was at home when “ they urgently called us”. He did not say anything to his family “because they were preparing the house to host people on those days.” “So I lied to my family and I said that we were going to military training for some time. Then I left, and later they found out that the war had started,” Aslanyan says.

In addition to leg injuries that the war caused him, Aslanyan also suffered serious organ injuries, “in lungs, liver…” he lists. However, if there is an opportunity, when he recovers, he would like to continue serving as a soldier. “I won’t think about it for a second because I love it a lot. I really liked to serve in the army – I was wearing the uniform with love,” he adds.

Invisible

Wounds

The 44 days when Armenian teenagers have become adults

In an alley in Yerevan, Armenia’s capital, next to a row of parked cars, which leads to the central Sayat Nova street, there is a mural of a beardless young man with brown eyes in a military uniform and helmet.

Next to it, another portrait, of a boy with a cap on the flag of Armenia, reads 2001-2020. He died at the age of 19.

Walls across Armenia are painted with colorful murals with faces of young men in military uniform. They remember the deceased soldiers in the 2020 war.

For a small country like Armenia, with just 3 million people , “it is a demographic catastrophe”, says Dr Irène Nigolian, a psychiatrist and specialist in the transmission of trauma, who explains “very quickly, in 44 days of the war, Armenia lost a third of the new generation of men,” she estimates.

The invisible wound, trauma, affects thousands of boys more.

One in five people (22%) who have experienced war or another conflict in the previous ten years "will have depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia," according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), which has analysed the prevalence of mental disorders in conflict-affected settings..

The support of Armenian psychiatrists in the diaspora

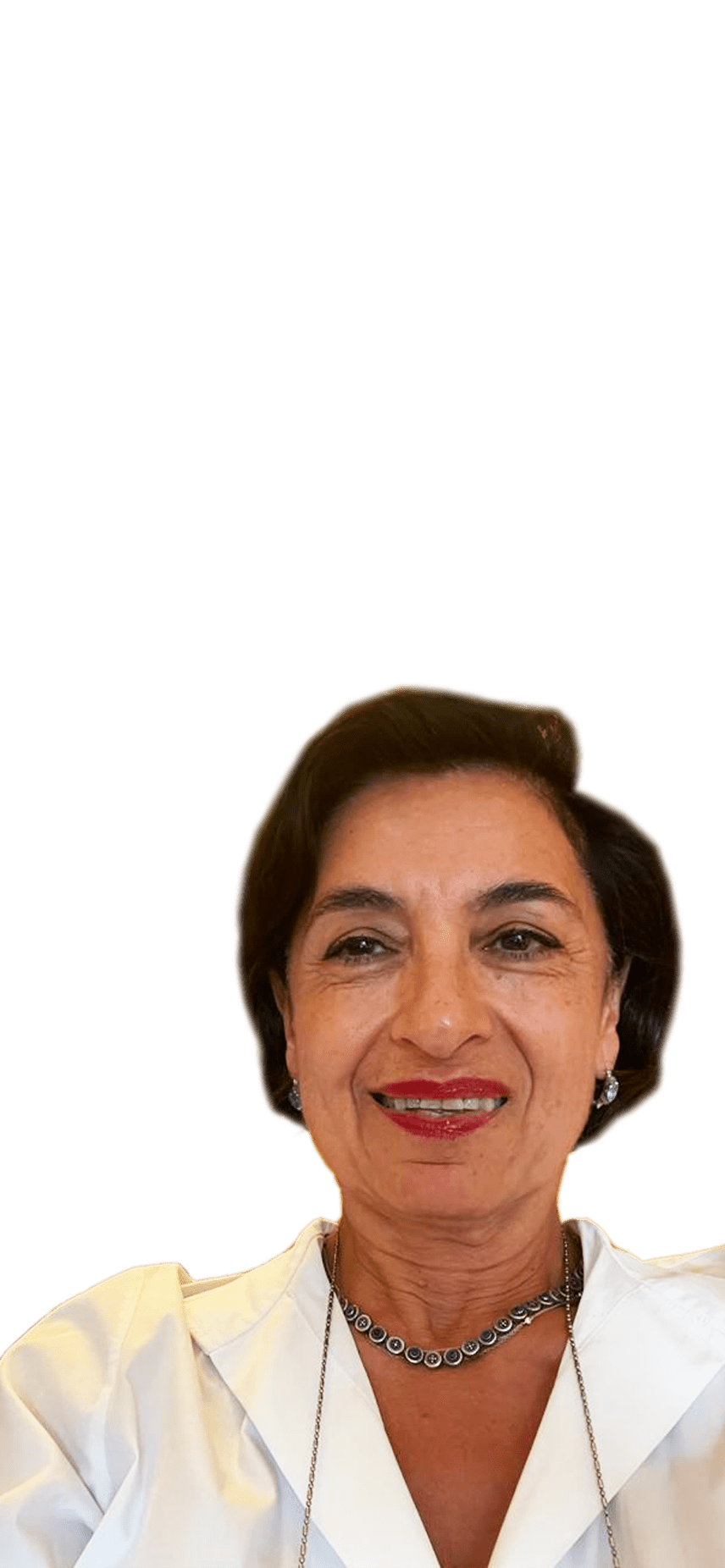

Dr Nigolian is part of the team of Santé Armenie, a collective of French-Armenian psychiatrists in the diaspora who came together at the outbreak of the war in 2020 to support the development of psychiatry in Armenia and the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders.

An estimated 7 million Armenians live abroad. It means there are more than twice as many Armenians outside as inside the country. When the war broke out, Armenians in the diaspora wanted to do something.

“The doctors of the Armenian diaspora felt that they could not sit idly by,” says Dr Irène Nigolian sitting in a café in the central Cascade Square in Yerevan. She says that the idea of Santé Armenie came from Arsène Mekinian, a professor of internal medicine at the Sorbonne in Paris, who, as the war broke out in September 2020, started contacting Armenian doctors in France and a group of French-Armenian doctors was organised.

This is how Santé Armenie was created. Currently it is made up of 300 French doctors of Armenian origin.

“I joined them very quickly,” continues Dr Nigolian, who lives and works in Switzerland, and soon, after the war, in December 2020, travelled to Armenia.

The first step was to organize groups of different specialties: surgeons, rehabilitation, psychiatrists, etc., to respond to the different needs, and then, they came to Armenia. “It was very spontaneous,” she adds.

Then, they began online training with doctors based in Armenia on how to treat acute stress situations. But when they arrived in Armenia, Dr Nigolian remembers that they found something they did not expect: “We realised that the first thing we had to treat was our colleagues who had received a huge quantity of soldiers.”

“And when we say soldier, perhaps we think of someone very strong, but it was a group of adolescents between 18 and 21 years old, who were doing their military service and were not prepared to be on the first front of a war,” Dr Nigolian continues.

These young men “found themselves in a horror film with all that 21st technology, seeing their friends dying in explosions, losing their legs, arms,” she adds.

Mental health in a drone war era

“A new weapon complicates an old war,” entitled Los Angeles Times. Some analysts have branded the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War as "the first postmodern conflict" in that it was the first in which unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) overwhelmed a conventional ground force.

Thanks to the benefits of oil and gas, Azerbaijan has modernised its arsenal in the last two decades, including “an impressive drone arsenal”, as the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) described. Israel and Turkey are the main suppliers of drones to Azerbaijan, among them is the Turkish drone Bayraktar TB2, which has been later used in Ukraine.

The Armenian arsenal consisted of weapons mostly made in Russia, including several ballistic missiles inherited from the Soviet Union following its collapse. According to the CSIS, they also used Russian Iskander missiles, a Chinese WM-80 multiple-launch rocket system and a smaller indigenous system of drones.

“The brutality of the fighting was due in part to the large-scale use of armed drones”, wrote Benjamin Brimelow at the Business Insider.

Thus, the Santé Armenie collective created what they call "a Psycho Trauma Task Force" to treat doctors and soldiers who had witnessed the horror of war. They visited hospitals and met professionals who had received soldiers just after the war "because local specialists were trying to do the first necessary things that are the physical injuries, but the mental health service of the country was not ready for this," Dr Nigolian says.

Among the wounded young men Dr Nigolian visited, she found two types of situations: “On one hand, those who had seen such horrible stories and they were not able to relate with their families in the same way because they had a kind of secret about this horror.” She says they were “young men who in 40 days became very old.” But on the other hand, she also found some 18 or 19 years old young men “who were very thankful to be alive” and “suddenly paid attention to nature, to the sun or the trees, like it was a miracle”.

There are two stages of treating trauma, according to Santé Armenie. First, the immediate psychological help that soldiers and civilians affected by the war require and second, treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which manifests itself with various symptoms such as nightmares, mood swings, anguish triggered by a sound and physical manifestations such as sweating or nausea.

Santé Armenie aims to create “a constant and lasting relation” to help develop psychiatry in Armenia “so that next time they will be ready for this kind of situation,” Dr Nigolian concludes.

The invisible wounds of those who have not said goodbye yet

The war has impacted not only the young people who fought but also the families of those who were taken away by the war.

The street Yerevan's military cemetery (Yerablur) is located in is called “Alley of Glory”. Since the late 1980s, the bodies of Armenian soldiers who perished in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict have been buried on a hilltop on the outskirts of the Armenian capital.

Parents, siblings and widows walk up the steep slope with bouquets of flowers on days of anniversaries. Naira Melikyan, the mother of Hayk Melikyan, one of the young soldiers who died in the 2020 war, says that it took her months to recover the body of his 19-years-old child, Hayk, "well, a piece of him," she points out. She, along with other parents of the deceased youth, celebrate all their children's birthdays together.

However, many families from both sides of the conflict, Armenians and Azerbaijanis, are still waiting to say goodbye to their loved ones.

“More than 4,500 people have been reported missing until today, and this figure has been extended to another more than 300 people after the 2020 war,” explains Zara Amatuni, spokesperson of the Armenia delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Mrs Amatuni explains that living without knowing the whereabouts of a child is a feeling similar to the desperation that some parents can suffer for a few minutes when they don't know where their baby is, “the same, but a permanent anxiety,”

ICRC has worked over the years with the families of the missing persons, that is, people who went missing in war or whose families do not know what has happened to them, causing anguish and uncertainty.

They have provided several programs for the families of the missing, helping them to understand their rights and working on several needs, including mental health, legal support or microeconomic initiatives, since, in many cases, the missing person is also the breadwinner.

The invisible wounds of internally displaced persons

“Mental health problems can also affect those forced to leave their habitat,” Zara Amatuni continues.

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) of the UN was one of the organisations that supported the displaced people following the 44 days of the war. Among the initiatives, they launched a mobile clinic across the most affected areas that reached 15 communities and screened 750 persons, according to IOM data.

IOM also supported the rehousing of some people with mental problems.

One of them was Yasha.

The journey from Stepanakert seemed to Yasha to take forever. His legs ached after hours of sitting in the car in the traffic jam of cars and buses of people leaving their homes in Nagorno-Karabakh. The almost 90-year-old man was evacuated as the war broke out in Nagorno Karabakh and resettled in Dzorak, a centre for people with mental disorders on the outskirts of Yerevan.

At the entrance to Dzorak centre, an old building whose bathrooms have been renovated thanks to a grant from the Japanese government, a woman is sitting on the steps with a smile on her face and waving. One inmate plays an old piano. Another wears an outdated military outfit and patrols the halls as if he were on duty.

The impact of displaced persons with disabilities was even greater.

“170 people were brought to the Dzorak centre at the very beginning because they needed to be allocated”, Mamikon Tosunyan, Director of Dzorak centre. “It was very hard to allocate them because most of them were not mentally ill. They were elderly mostly,” he adds.

“And very emotional”, a smiling Ruzanna Mkrtchyan, a general nurse at the Dzorak centre, says, posing hands on her white gown. They explain that, at first, the problem was that most of the people had fled with no documents, so they started to search who was who, which diseases they had, and if they had relatives.

“A new thing”

“This war was a new thing for Armenia”, concludes Rima Kabrilyants, Armenia’s National Coordinator of Emergencies and Operations at the IOM. “All these handicap boys and young men with mental problems, we did not have something like this before”. “It is our new reality, and these young men are going to be our future generation, so the country has to adapt for that”, she concludes.

Disturbing memories

Not far from there, in Proshyan, 15 km outside Yerevan, a modern building with a garden, recently inaugurated under the name of “Rehabilitation Centre of Heroes”, aims to offer psychological and social rehabilitation for soldiers.

It was built thanks to crowdfunding launched by Suren Areents, a former Armenian journalist.

Showing a room with a comfortable armchair and various technological gadgets, Mr Areents explains the press that they expect to treat soldiers using Virtual Reality Exposure (VRE) therapy. In this image, Anatolii, the translator of these interviews for Outriders, is testing the VR headset. "Breathe in, breathe out," a computer voice says.

The center was not yet fully operational when Outriders visited in March 2022.

Using virtual reality in exposure therapies to treat any psychiatric or psychological disorder is not common in Armenia. Still, in some countries, it has been tested in multiple randomised clinical trials since the 1980s.

The first study about this kind of exposure therapy was published in 1995. In a pilot study, it was first used to reduce fear of heights using virtual environments, including footbridges and balconies. Since then, virtual reality exposure therapy has been increasingly used for treating several anxiety- and trauma-related disorders, including phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The image of this hospital room is an example of Virtual Reality (VR) used by UCF RESTORES, a nonprofit clinical research center at the University of Central Florida, dedicated to changing the way PTSD is understood, diagnosed and treated.

“The technology is not the treatment, but it will make the treatment better,” recalls Dr. Deborah C. Beidel, executive director at UCF RESTORES.

Dr Beidel explains that “trauma changes someone forever, but with the right treatment, they can overcome the trauma and reclaim their lives.”. “They will be different, but that does not mean they cannot take control and move forward,” she adds.

For instance, at the UCF RESTORES, people with PTSD reported that specific characteristics of the traumatic event, such as sights, sounds and smells, continue to create distress every time that they encounter that sight, sound or smell in their daily life.

“If you think about a first responder who had to rescue a child who drowned in a swimming pool, every time they see a child who looks like that deceased child, they may become very anxious, have an anxiety attack, begin to have nightmares and perhaps decide that they cannot go places where they might see a lot of children,” Dr. Deborah Beidel says.

But how do traumatic events affect a person's mind and how it is treated?

We have chatted with Andrew M. Sherrill, an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry specialised in Virtual Reality at the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, in the United States. His research interest is understanding how minds process a traumatic event and subsequently retrieve encoded information.

A lack of professionals to treat so many new patients in Armenia

Sleep troubles, feeling upset, disturbing dreams and memories, being super alert, negative feelings, avoiding memories and loss of interest were the main symptoms that some of the patients of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war presented, according to a study conducted by clinical psychologist Liana Terzyan and colleagues. For her, the first challenge that Armenia must address to treat all these new patients is the lack of professionals.

In 2017, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health, Dainius Pûras, found that despite "commendable reforms", people who want to treat their physical or mental health in Armenia, "still face serious barriers linked to an outdated approach to healthcare and persistent inequalities”.

Pûras also described mental health policies in Armenia as “outdated” and identified “signs of this vicious cycle in the Armenian mental health system, when people with mental health conditions are too easily and too often hospitalised in psychiatric hospitals, tend to be overmedicated, and then confined for long periods in large institutions, labelled as chronic patients.”

The road is long. While Hayk, Ishaan and Alek are treating the visible wounds, for many others across Armenia, the nightmares return daily when the light goes out, and the invisible wound remains untreated.

A country can take 50 years to get over the trauma, according to Santé Armenie.

STORY CREDITS

Story, photos and videos by Lola García-Ajofrín

Web development by Piotr Kliks

Design by Tina Xu

Translated by Grzegorz Kurek and Anatolii Tokmantcev

Produced by Outriders

UA-Music is a project showcasing young Ukrainian artists creating music despite the war, both in Ukraine and Poland. For them, music is a form of resistance, survival, and community-building. The project promotes Ukrainian culture, proving that in times of crisis, concrete actions can change reality.

In Arizona, between Nogales and Sasabe migrants can find shelters once they cross into United States. Those places are run by various groups and non profits providing support to migrants in the state. Here is one of those camps these days called "old camp" as it was one of the first ones.

What happens when someone you love goes missing on a European border? There is still no European law that requires governments to identify the dead and notify their families. Over half the graves we found in our investigation were buried without a name. We present the stories of Europe’s border graves in three collections of 360 degree videos, taking us to border cemeteries in Spain, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, and Poland.

The European Union, associated with the policy of open borders, is currently surrounded by over 2,000 kilometers of border fences.

Get up close to what one of the most man-made rivers in Europe looks like.

An estimated 1,400 girls are not born every year in Armenia due to a rooted preference for male children. The son-bias combined with a lower birth rate, has led to an alarming number of sex-selective abortions. Community activities, various laws and television shows are addressing the issue - with positive results. But is the actual problem being tackled?

29.37 kilometers – at the time of writing this report, separating Kramatorsk, the temporary capital of the Donetsk Oblast, from the front line. One third of the 220,000 inhabitants remained. In the deserted city you can see mostly soldiers. They head to the front or return from it to rest for a while. The fate of Kramatorsk and eastern Ukraine depends on the outcome of fierce fighting. Military trucks and heavy equipment rush to nearby Bakhmut every day.

Over 3.5 million people were evacuated by train in Ukraine in the first 50 days of the war. 94 Ukrainian railway workers were killed, and 99 staff were injured during the evacuations. How have Ukrainian Railways helped to save thousands of lives amid war?