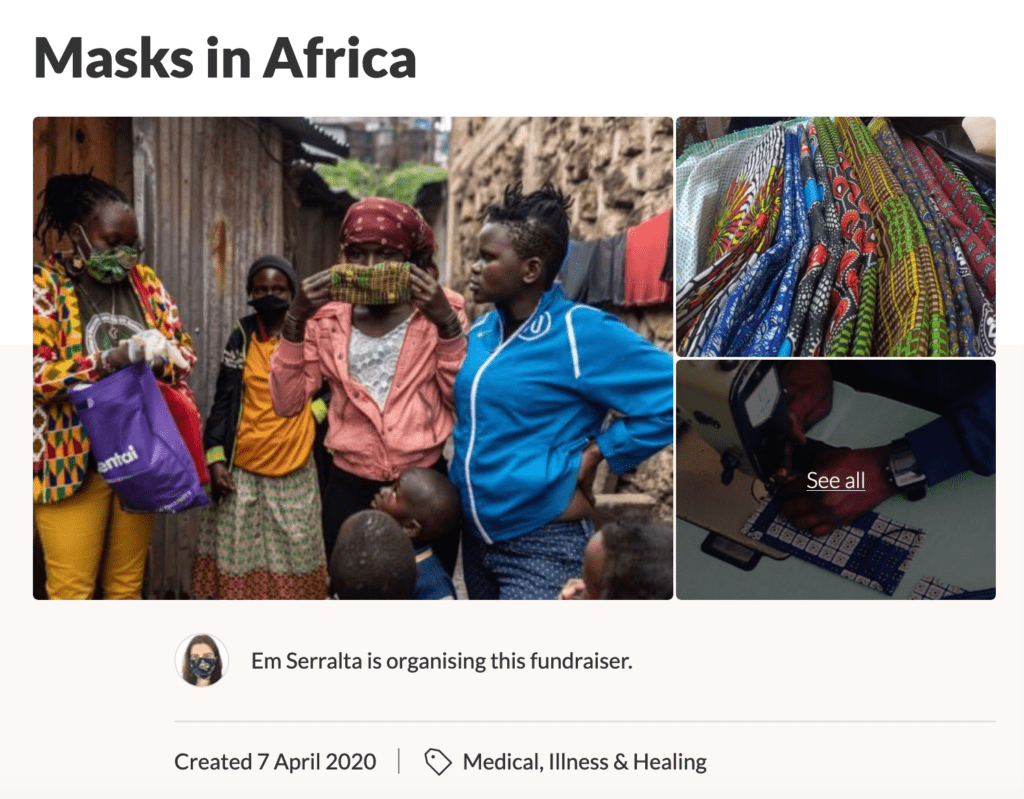

Non-profit delivers masks for the vulnerable in Africa and gives jobs to local tailors

A non-profit organisation African Masks distributes cloth masks in several countries across Africa. While some governments introduced compulsory mask-wearing, many impoverished communities cannot afford a mask. Teams of African Masks volunteers distribute masks to the most vulnerable and populated communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Senegal, Kenya, Benin and Nigeria.

In the first month, local tailors, who are mostly women, were able to sew nearly 8,500 masks. It also became a much-needed job opportunity for them. This venture is supported by crowdfunding and almost reached its initial goal to collect €4,500.

Emilie Serralta, a humanitarian worker who founded African Masks, tells Outriders how her initiative brings employment to local tailors and how they allocated masks fairly and safely.

You are based in Europe. Why did you start a campaign to help sew and distribute masks in Africa?

Since I lived in several African countries and worked with them for the past 20 years, I started discussing the issue of mask-wearing with my colleagues in Nigeria, Benin and Kenya. I knew that social distancing would be a challenge in public transport or informal settlements in large cities. Masks seemed to be a cheap and useful tool against contagion in locations where social distancing and sanitation is a challenge.

Also, some governments have made it compulsory to wear masks, without making masks available and affordable to all. However, by doing so, they made people even more vulnerable. If you cannot afford to buy a mask, you certainly cannot afford a $200 fine for not wearing a mask. I also hoped that masks could become an alternative to complete lockdown, which is unsustainable in developing countries.

How do you make sure you allocate masks fairly? Do you have contacts on the ground in those countries so that you understand who is in urgent need?

There is an important community mobilisation in Africa; it is endogenous, it started there. Many grassroots groups have done tremendous work and started working early on prevention, sanitation as well as food distribution. African Masks is coming in to support an already existing process.

As we are working with grassroots organisations, we coordinate efforts to target most vulnerable groups, mostly in urban centres. These are people whose job forces them to contact with others (market traders; public minibus drivers; taximoto), people who live in places where cases of Covid-19 were confirmed; people living in informal settlements (i.e. slums), where social distancing and sanitation is a challenge; or people who are vulnerable (for instance, Goma Actif distributed 300 masks to older adults in homes in Goma, Democratic Republic Congo).

That’s a long list of people, and we can’t give masks to everyone, but having criteria helps. For instance, in Nairobi, we targeted one specific local market where one of the traders had fallen ill, and we gave masks to all the other market traders.

Tell us how the African Masks initiative managed to provide jobs for tailors in Africa.

There is a tailoring tradition and beautiful fabric in Africa. People still buy clothes that were made at tailor shops. In some places, tailors are local businesses, and they charge us the market price for masks. In Kenya, we work with the fashion house Tenge Vuli (www.tengevuli.com). It is a social enterprise, and they produce the mask at its cost, so they don’t make a profit out of it.

In Benin, we work with a group of women leaders who collected fabric, cut it and gave it to a tailor for sewing. It saved a lot of money, so they alone could produce 1,5000 masks. In total, at least 30 people were involved in the masks-making to date. All of them were paid, except the women volunteers in Benin. All the money that we collect is spent on masks, except for some obvious fees, such as for bank transfers or by the crowdfunding platform.

I am coordinating mask production, doing promotion, managing fundraising, while being in Europe. Our partners on the ground do the distribution and awareness-raising job. And nobody is paid, apart from the tailors.

How do you make sure that you, your volunteers and those who they are helping are safe when you deliver masks? Do you have any safety protocols?

Those who distribute masks are wearing it themselves. For example, in Kenya, our partner CGHRD had been doing food distribution before we started working with them, but they wore no masks, so we offered those. Some groups were already aware of mask-wearing, such as Goma Actif.

Then we had discussions about how to carry out distribution safely, how to explain mask-wearing to people, how to clean masks. People leading the distributions trained other members of their group. We have a WhatsApp group for all our partners in the different countries where we can exchange tips on distribution and safety.

It might be challenging, but they are also changing their strategies on mask-delivering to avoid chaotic situations because many people are now in urgent need.

Did you analyse where most of your donations come from?

These are my own money, donations of my friends, family, friends of friends, and lately, from other people who read articles and saw our activities on social media platforms. It comes mainly from Europe, but also from Africa.

What is the future of this initiative?

Until masks are produced on a massive scale and given out to everyone, there is a need. The main challenge is how to continue financing the production of the masks, and we are thinking about alternatives to crowdfunding.

Here is the list of African Masks’ partners in Africa:

In Kenya: Coalition for Grassroots Human Rights Defenders (CGHRD) and Kitisuru Citizen Forum. You can find them on Facebook here and here. And on Twitter: @cghrdkenya or @rachaelmwiks.

In Nigeria: Women Africa. On Twitter: @WomenAfrica35.

In Benin: Fondation Reine Hangbé. On Twitter: @inforeinehangbe.

In DRCongo: Goma Actif. On Twitter: @Gomactif and on Instagram: @Gomactif.

In Senegal, Amnesty International Senegal and Y en A Marre, a pro-democracy movement.

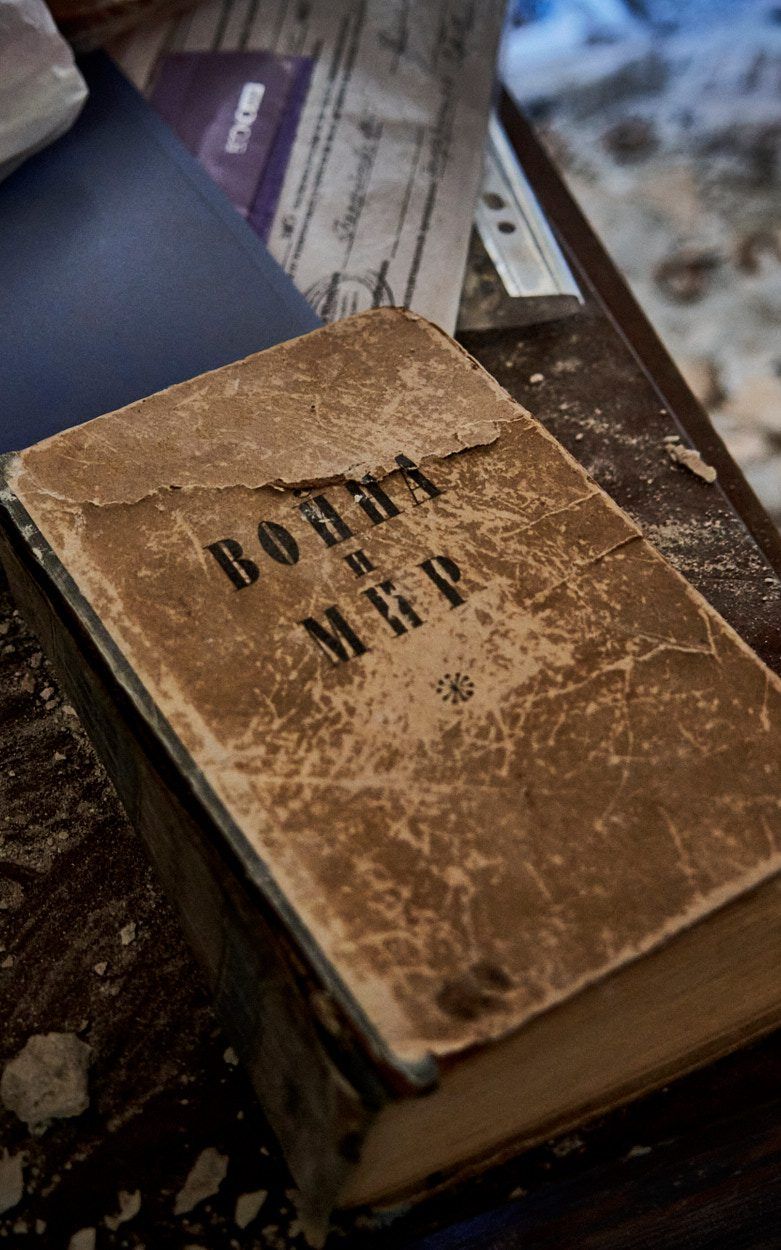

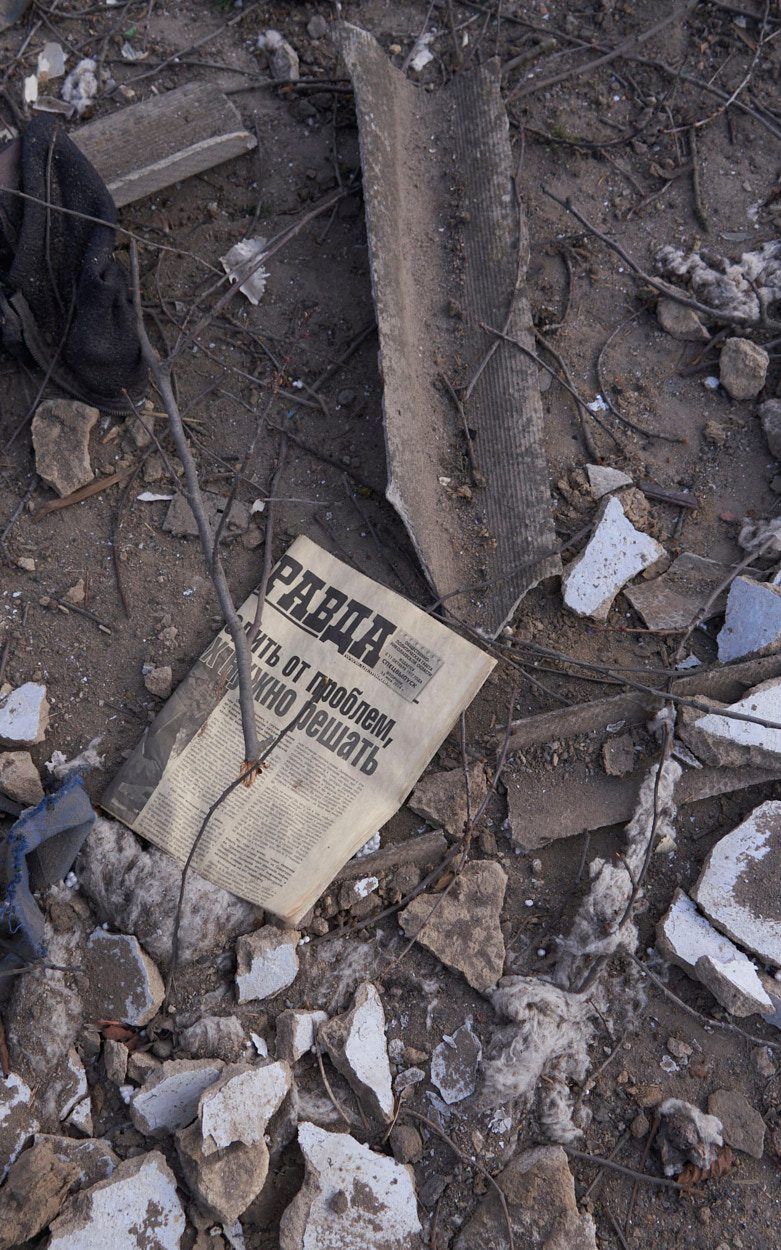

Photographs courtesy of Michael Kalamo.

The screenshot with the mask distribution as of May 19 was shared by Emilie Serralta.