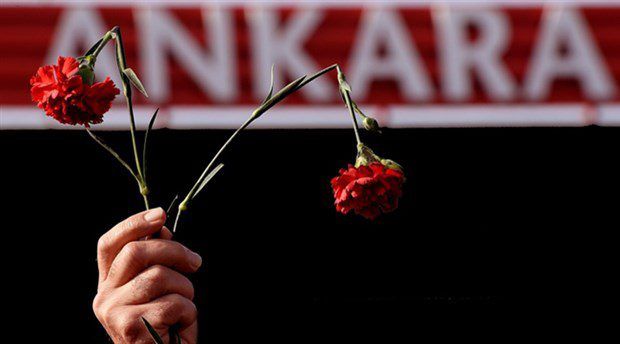

It was meant to be a massive show of support for peace and democracy. It is remembered as the deadliest terror attack in Turkey’s history. It was our darkest hour and, three years later, we are still waiting for dawn.

I had intended to be one of the thousands of people attending the rally in the centre of Ankara on October 10, 2015. I was working at the time with the media monitoring team of the electoral observation mission ahead of the snap general elections called for November 1, 2015. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) had failed to obtain a working majority at the general election the previous June and rather than entering into a coalition had decided to go back to the voters. I spent an entire week convincing my OSCE colleagues that we had to observe the rally to assess fully whether the electoral process was fair and free. I now confess my ulterior motive was to join in the march rather than spend time with a stopwatch in front of the TV to monitor how much broadcast time would be allocated to opposition parties.

Participants started arriving at the capital’s main train station, joining friends and comrades before peeling off to make their way to the site by midday, when we were also planning to join them. The mood was joyful, and as is the custom, many were holding hands, dancing a folk “halay” in a semi-circle. It was a few minutes past ten o’clock when the first bomb exploded. It was followed moments later by a second suicide bomb explosion. I remember seeing “the breaking news” report on a website, which initially indicated that it was just a nuisance blast designed to cause noise and confusion. Then the images started coming through, and I screamed in panic at the sight of bodies lying on the ground.

After the initial shock and disbelief, my first feeling was horror. It was quickly followed by rage and dismay – how could such an attack happen in the centre of the capital city, a city swarming with police, military and intelligence officers? Then came guilt. “Why wasn’t I there?” The sense of helplessness was overwhelming, and I was drunk with remorse. The rush of feelings and thoughts eventually reduced to only one: pain. The grief was so intense it resonated in every cell of my body.

Terror attacks are certainly not specific to Turkey. However, the fact that what was targeted was a peace rally shattered more than merely people’s illusion of security. Our entire youth we are told that good people always win. Though innocent people die, justice would still be served, sooner or later. The massacre claimed 103 lives – men, women and young people and even children. I had wanted to march with them, and to share the same dream. They were cheerful, hopeful, caring. Some were attending the first rally of their lives, and others had devoted their lives to social movements. There was nine-year-old Veysel Atılgan holding his father’s hand and 70-year-old Meryem Bulut, one of the “Saturday Mothers” whose son was forcedly disappeared in the 1990s. They were there quite simply because they believed the future could be better than the past.

The explosion rocked this belief. The pill had to be swallowed: while the ones who yearned for a better future were slaughtered; those whose neglect was responsible continued to rule with impunity even stoking a toxic political climate.

Truth and memory at stake

Turkey recently marked the third anniversary of the “Ankara Train Station Massacre.” It did so quietly. Justice has still to be fully rendered, and public memory remains undisturbed except with a few acts of solidarity– none of them official.

In August this year, nine people believed to be connected to ISIS were each sentenced to 101 life imprisonments, no state official has been called to account. Seventeen of the suspects are still fugitive, and the investigation has left many questions unanswered.

The friends and families of those who died have been denied a public enquiry but also public recognition for what they have been through. There has been no official commemoration ceremony for the last three anniversaries of the attack, nor was there any significant public statement made by any government official. Commemoration events attended by the families of the victims were even dispersed by the police with tear gas.

This reluctance reveals a certain insolence towards the fate of the victims, not just for what they suffered but who they were. Why were the victims denied official commemoration just because they were protesting the government’s policy? That policy was to turn more vicious after military operations were launched in the mostly Kurdish southeast of the country a few months later. Does staging an anti-governmental rally or not being an AKP voter make people less of a citizen?

Two disturbing questions, in particular, have remained in many people’s mind: How can a state be expected to effectively ensure the security of people whom it considers as dissenters, and whom it then deems unworthy even of being commemorated as a victim? Can a state which doesn’t feel responsible for ensuring that the memory of the deadliest terror attack in the country’s history is not forgotten feel responsible for unveiling the truth behind the attack?

“In a place where people who call for freedom and bread are in prison, and the ones who call for peace pay the price with their lives, we are aching,” said Mehtap Sakinci Coşgun at this year’s commemorative event in front of the Ankara Train Station. He was speaking on behalf of the families of victims and people who were injured during the attack. “But this pain gives us a dignified responsibility. We will fight for justice. We will make our voices heard,” she said. Coşgun lost her husband Uygar, a lawyer, during the attack.

A more intimate event was the first screening of the documentary Elif for Elif Kanlıoğlu, another victim of the attack, at the Istanbul Literature House. Elif was only 20-years-old when she was killed. Her memory is a balm for those who share her hope for peace. Telling her story meant telling the stories everyone who lost their lives that day, anyone who attended the rally, anyone who wanted to attend and couldn’t and even every single person aspiring for peace, said Elif Ergezen, the director of the documentary. In a sense, continuing the fighting for peace is the best tribute.

Turkey has experienced much violence over the last few years. Some, like the military operations in the southeast, was sponsored by the state. But the day when 103 people who gathered to call for peace died in two successive suicide bombings, the day when peace became a deadly word, is a tragic turning point. It is a moment when the state failed to show respect for its citizens killed in broad daylight.

Truth and keeping their memory alive are not a partisan act but essential for society to heal. No one calling for peace, freedom and dignity should ever meet such a fate. That responsibility falls upon every one of us.