Black bags full of different rubbish that is difficult to recycle. Polish waste management system is built in a way we do not have to see the waste. To change the system, we have to find a municipality that will dare to look into the garbage we produce.

Recycling half of the produced garbage is the goal that all EU member states are to achieve in 2020. Theoretically. According to recent Eurostat data, only 34% of collected waste is recycled in Poland. We are far behind Germany (68%), Slovenia (58%) and Lithuania (48%). And yet Polish activists point out that the government figures sent to the European Union are higher than the real ones.

– Statistics Poland (GUS) gives numbers plucked out of thin air. I have analyzed the municipalities’ reports, and I assume that only 17.5% of waste in Poland is recycled and we produce approx. 12.5 million tonnes of waste annually – says Paweł Głuszyński, a waste expert who works for the Society for Earth (TNZ).

We have a lot to do. And recycling is just another stage of waste management, the third one to be precise. So it is a rather remote stage. Since 2015 EU objectives have brought us closer to the gradual building of a circular economy. Prevention is at the very top of the waste management hierarchy, i.e. striving to keep it as low as possible. Then there is reuse, recycling and other methods of waste recovery. Throwing out the garbage is at the very end.

There is a certain municipality in Europe that manages to stick to this hierarchy in a pretty incredible way.

A miracle diet for garbage

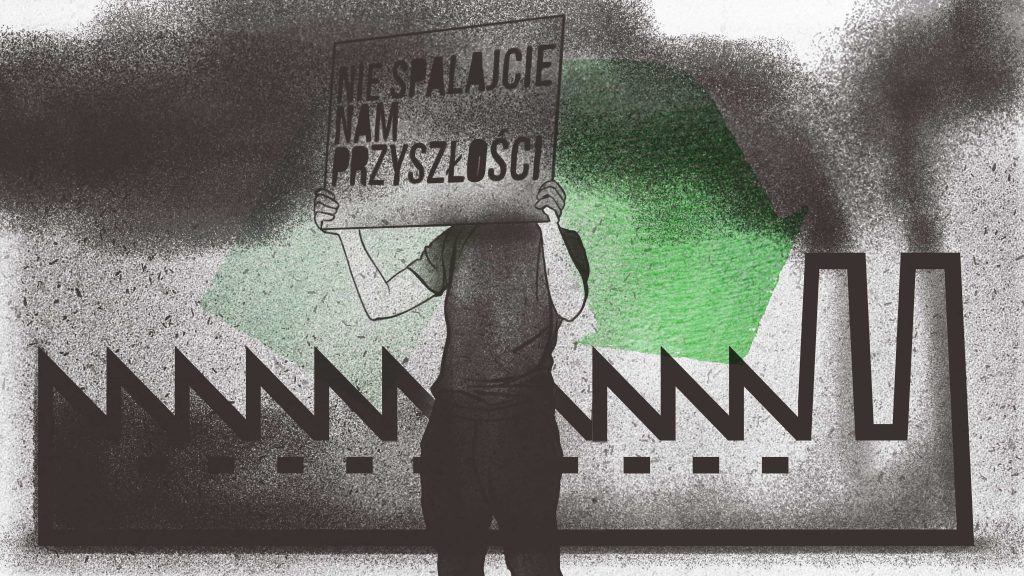

It all started with an incineration plant that has never been built. Why? Because Rossano Ercolini did not agree. He is a teacher in a primary school in Capannori, a municipality in the north of Italy, where 46 thousand people live. He protested on the streets of Capannori waving the “Don’t burn our future” banner. He mobilised thousands of inhabitants. Dr Paul Connett, a chemistry professor and an expert on incineration and zero waste, supported the social action with some more arguments. It was in 1997. More and more residents became aware of the dangers connected with building the incinerator plant.

On the other hand, they also realized the need to deal with garbage. Ercolini claimed it is all about reducing the amount of garbage. He prepared a pilot program of selective waste collection at source (“door to door”), launched an educational campaign, he actively supported other towns and cities in protests against building the incinerator plants. In 2007, he managed to convince councillors to sign the Zero Waste Strategy. Capannori was also a pioneer in establishing the first in Europe Zero Waste Research Center in 2010. Today, the municipality has one of the highest waste segregation rates in Europe – only 18% of waste becomes mixed waste. The goal is 0%.

What has really happened in that small municipality?

When asked about the reasons for the municipality’s success, Capannori politicians tell about two things: door-to-door waste collection and active consultations with residents. People were involved in brainstorming to think about how to work together towards zero waste. They received leaflets on separating rubbish, a set of trash cans, composters and the instructions on how to use them. There was also individual training on how to correctly separate waste. The so-called waste ambassadors also did great in Great Britain (Voice of Irish Concern for the Environment and Keep Britain Tidy campaign) and several regions of France (volunteers were part of an information campaign in 40 associated municipalities belonging to SCOM est Vendeen).

The door-to-door waste collection system began to be introduced in small towns, where it is easier to control it. In 2010 it was functioning in the entire municipality. Capannori informed the residents about the effects of their activities. It increased their contentment and satisfaction. Nowadays 99% of people separate waste in Capannori municipality. There are shops where products are sold by weight: pasta, oil, vegetables, local beverages, and the city offers a tax discount for reusable and non-packaging solutions. There are milk vending machines where you can use your bottles. Local farmers fill them with milk, what benefits everyone: producers, residents and the environment because there is no place for a long distribution chain and transport from large dairies anymore. A sensational result was already achieved in 2010 – 82% of waste was sorted.

The garbage bag

The traditional waste management systems are designed to protect us from looking at the garbage. According to Professor Paul Connett, a zero-waste expert, “landfills are burying the evidence, incinerators plants burn it and emit toxic smoke and particulates, and then we breathe harmful nanoparticles that can cause cancer.” To make a change, you must make the garbage visible for the people.

The first Europe Research Center Zero Waste was created in Capannori in 2010. Although it operates in one small room, the effects of its activities are impressive. The Center cooperates with a team of specialists, including waste management specialists, university professors and industrial designers. Together they deal with the garbage step by step.

First, they analysed a typical garbage bag, the black box of our homes, full of mixed waste that we do not know what to do with. That is what generates the highest costs for the environment – the mixed waste. They took samples from various municipality’s households (and the garbage bags in Capannori were already pretty light back then). It turned out that the average bag was filled with: leather and fabrics (16%), diapers (13%), organic waste (approx. 11%), and various types of plastic (28% in total). Most things did not have to be thrown away at all, so they began to think about what to do with them.

The Reusable Center was established a year later, and damaged goods can be repaired and left for anyone else’s further use. Over 93 tonnes of items found its place there, including furniture, shoes and toys. There are also training sessions in carpentry, upholstery or sewing that support the idea of reuse. Ercolini calls that place the “green island”.

– The Center record data show that our habits are changing, partly thanks to the city’s policy. Back in the days, people threw everything away; now they realise that taking care of objects is not only good for the environment, but also for those who can buy them at a more affordable price.

The municipality supports the use of reusable diapers – it gives them to parents of newborns and subsidises the purchase of new ones. The diapers are available at local pharmacies.

Vast amounts of coffee capsules were also found in Italians’ garbage bags. So the industrial designers met with the producers – Illy and Nespresso – to develop biodegradable or reusable capsules.

Capannori is a true leader when it comes to making garbage bags lighter. Between 2004–2013 the average garbage bag lost almost 39% of its weight. The municipality inspired Europe. Four hundred local governments in Europe have taken a similar path. Unfortunately, nobody in Poland. Even though in 2018, five environmental organisations offered help to local governments in creating a more sustainable system of waste management.

System Solutions

– I guess we should not only count on residents or local governments to take the initiative, should we? – I ask Piotr Barczak, a waste management specialist at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), which represents over 150 environmental NGOs.

– We shouldn’t, of course. However, we need a pioneer – Barczak believes. – A municipality in Poland which will show that a change is possible. I am convinced that it will cause an avalanche. Capannori is an inspiration; many applications can be implemented immediately, others, such as the Pay As You Throw system (you pay as much as you throw away), require some earlier education. In those Italian regions where it was introduced, microchips are placed on garbage bags, so it is easy to identify their owners. If the residents fill more than eight garbage bags a year, the municipality calls them to pay. People sort as high as 90% of waste in these places.

Portal Samorządowy (the local governments’ web portal) published an article two years ago in which the municipalities were urged to join the zero-waste program. Experts explained that despite the fears of municipalities, the green policy pays off. Paweł Głuszyński from the Society for Earth, a waste management expert, admits that although there must be some investment costs at the beginning and the costs of waste collection may increase, the costs of waste management drop sharply. If the municipality collects pure raw material, then it can go straight to the recycler, and the material is also more attractive for recycling.

The Capannori example confirms that. In 2009, the city council saved around 2 million euros on waste recycling. The money was spent on a 20% reduction in waste tax per capita and building a composting plan. Fifty new workplaces were also created in the region. Everybody benefits from as little waste as possible – the cheapest waste for the buyers, for the municipalities and the environment is the one that has never been created.

I ask Piotr Barczak what lacks the most in Poland, apart from a role-model municipality, to move towards a circular economy.

– We need system solutions implemented at the national level that enforce pro-ecological actions on manufacturers. Following the EU Waste Framework Directive, which speaks of extended producer responsibility, he must bear the costs of collection and recycling or storage or waste incineration. It means that the more difficult and more expensive the product’s recycling is, the more the manufacturer should pay within his duties of the extended responsibility. Obviously, the manufacturer’s costs will be passed on to the customer. However, not every resident is a customer. Today, the one who does not drink fizzy drinks pays for the used bottles. This system is unfair, both ecologically and socially.

There are system solutions that work anytime, anywhere. One of them is the deposit and return system.

Back to the past

All EU countries that have introduced the deposit and return system have significantly higher rates of selectively collected waste, and thus – the recycling waste. For example, Germany or Lithuania collect up to 90% of beverage packaging. Poland collects no more than 40% of beverage packaging. Moreover, every year we produce 4.6 billion PET bottles just for mineral water.

– The deposit and return system is one of the most effective instruments against plastic contamination of the environment. According to our research, 88% of Poles support its implementation – says Joanna Kądziołka, a member of the Polish Zero Waste Association and the coordinator of the initiative “Wrzucam nie wyrzucam (I throw in, I don’t throw away)”.

How does it work? Consumers pay not only for a drink but also an additional amount (in Germany it is 10-25 euro cents, in the Baltic States it is 10 euro cents). They get the money back when they bring the packaging to the store. Usually, there are special vending machines in the stores that read product codes, and the money can be picked up at the checkout or spent in the store. Thanks to the system, the collected packaging is clean, and hence – attractive for recycling companies.

Some readers probably remember a time when milk and cream were bought in reusable bottles. I ask Barczak about who decided that we do not use that system anymore.

– The manufacturers – because reusable products were less convenient for them. I mean they were less massive and more local, more retail. You have to clean the packaging, which means the internal costs increase. At the same time, they came up with the idea of disposable packaging. Mainly thanks to the plastic, the manufacturers expanded the markets, and they did not have to worry about picking up empty packaging. Nobody required that, so they gave up the selective collection and instead they started paying for cheaper disposal. Nowadays it costs pennies, but most of the packaging goes for storage or incineration. It means the producers do not bear the full external costs associated with the life cycle of their products.

The initiative ” Wrzucam, nie wyrzucam (I throw in, I don’t throw away)” deals with the myths that have arisen around the deposit and return system. Which is the most important one? That the system is expensive. The truth is, that it is financed by the manufacturers as well as from the sale of collected waste and the packaging the clients do not pay the deposit for (about 10% of all packaging). Another false argument against the deposit and return system is the lengthy implementation of it. In practice, the creation of the entire system, including talks with manufacturers, takes an average of four years. After passing the law, the implementation does not take more than two years.

Reusable packaging can be used up to 50 times, and the unique feature of glass means that it does not lose any of its properties during processing. Glass packaging is heavier when it comes to transport. Still, thanks to that, it does not travel long distances.

– Reusable packaging supports the local economy and shortens the circulation, which is another advantage – says Barczak. – The disposability is the worst thing in consumerism because there are no completely ecological materials. Only the systems are ecological.

It is difficult to find the disadvantages of the deposit and return system. Some underline the fact that usually, the poorest and homeless people collect abandoned packaging, and that is why they remain in the circle of exclusion. However, the experience of 10 European countries shows that people act very willingly. One hundred thirty-three million Europeans bring used packaging to stores.

The deposit and refund system is a big step on the way to a circular economy, but it cannot be the only one. This is where we can get the inspiration for a change – some countries are bravely stepping towards the zero-waste policy. In 2019 Bali banned the use of single-use plastic items. Single-use plastic shopping bags are banned in New Zealand from 2019. At the end of 2019, the ban was expanded on polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is difficult to recycle (it is used for meat packaging, cups or takeaway packaging). In 2020, Italy ordered the manufacturers to pay 50 euro cents for every kilogram of plastic placed on the market.

– We need a proper system that combines various elements: eco-design, shopping with our packaging, deposit and return system, appropriate composting, selective collection. The same method as in Capannori, but on a bigger scale. The system must be intelligent and flexible so that we do not get stuck in the investment trap and we should be able to adapt the system to the changing circumstances – adjust the size of the bins, the garbage trucks’ routes etc. – explains Barczak. – For example, Denmark and Sweden haven’t been able to overcome a certain threshold for waste collection for years because the systems blocked them. Incineration plants are connected to the urban heating system, so they must be continuously fueled by caloric waste such as plastics or paper.

Indeed, the change is not easy, and it requires some effort because residents need to be mobilized. But there is no other way. According to Julián Ercolini, the winner of the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize:

– Our history of zero waste gives hope that has spread all over Europe. If the community organizes itself, it can create sustainable solutions that can transform the whole society.

Scientific consultation:

Paweł Głuszyński (The Society for Earth)

Źródła:

- Raport European Environment Agency: Waste recycling,

- Reusable solutions: how governments can help stop single-use plastic pollution

- Raport Ellen Macarthur Foundation: Reuse, rethinking packaging

- Dyrektywa Parlamentu Europejskiego I RADY UE 2018/851 z 30 maja 2018 w sprawie odpadów

- Raport Zero Waste Europe, Przypadek #1 Historia Capannori, Aimee Van Cilet, Sierpień 2013, PDF, pobrany ze strony:

- Strona internetowa akcji „Wrzucam, nie wyrzucam”

- Artykuł nawawiający polskie gminy do udziału w Zero Waste

- Artykuł o wręczeniu Nagrody Goldmanów Rossano Ercoliniemu

- Surowiec, przewodnik po polskich praktykach bezodpadowych

- Opis projektu wspólnego zarządzania odpadami 40 stowarzyszonych francuskich gmin

- Opis programu Waste Ambassadors w Wielkiej Brytanii

—

Artykuł został przygotowany w ramach konkursu „#MamyWspólneCele edycja 2019 r.” Partnerem konkursu był Santander Bank Polska S.A.