It takes a brave bureaucrat to contradict Bertolt Brecht but Turkey’s top broadcasting watchdog did just that when it issued a million Turkish lira fine (€200k) for a simple kiss.

The victim of their costly disapproval was none other than the country’s new television hit Çukur, (aka the Pit). The fine was for the “screening of alcohol consumption, intense kissing, and lovemaking.” This was an over-generous and overbearing judgement, evoking a Lars von Trier-meets-Walerian Borowczyk moment. But who is to say how intense, “intense” really is. The offending scene included nothing more than an affectionate couple embraced in a gentle caress, and a soft kiss. And they were married.

The Pit, kind of a tacit Turkish homage to the Godfather, tells the story of a crime-ridden neighborhood run by a notorious kingpin, İdris Koçava, and his family. To the Koçava, all is fair game in the neighborhood, but dealing drugs. Yet, along comes a larger than life sort of an upstart, with the core ambition to shake things up. Just when Koçava’s about to throw in the towel, in a true Corleonesque twist, the youngest of Koçavas, Yamaç, , with looks to die for and his head in the clouds, enters the stage. Together with his significant other, he is about to reshuffle the deck.

“The human race tends to remember the abuses to which it has been subjected rather than the endearments,” remarks Bertolt Brecht, “What’s left of kisses? Wounds, however, leave scars.” The great master never watched Turkish TV.

The series has a fine caricature of a villain called Vartolu Saadettin (Saadettin of Varto). Yet this too caused offence, particularly in the small town of that name whose population is no more than 13k. The controversy simmers on as Vartovian after Vartovian filed a complaint with RTÜK – the acronym for the penalty slap-happy board that polices Turkish broadcasting.

Not long after this, a renowned government crony disguised as a sometime journalist claimed to have seen both the small screen and the big picture: Through its name, its logo, and its storyline, Çukur was not an ordinary TV show but “a secret code of an operation against Turkey architected by some certain people.” The revelation continued: “If it’s Turkey that’s at stake, no conspiracy theory is a conspiracy theory.” Indeed.

Then came the kiss. But this was just the beginning. The very same RTÜK hit the show with yet another fine of a million Turkish liras, this time for profanity, alleging that the already bleeped out broadcast enabled the audience to read lips and make out swear words.

Whether it was an imposition by the network itself, or by the easily offended watchdog is a mystery, but soon the show was seen to bleep out the word “wine” as well, let alone the consumption of it. Mind you, it was not a proclamation of sorts on the perils of wine drinking, but simply a popular song, with lyrics derived from a quatrain of the great poet of the East, Omar Khayyam no less: “The clouds spread over the face of the heaven, and rain patters on the sword. How could it be possible to live for a single second without crimson BLEEP.”

Never mind the fact that there is a centuries old well-established precedent that claims Omar Khayyam’s “wine” was his way of describing the Deity. He was, if nothing else a free, farcical, and often defiant spirit, befitting a Sufi poet. There’s truth in wine (if I may be allowed my own mystic moment), and a single bleep is worth a thousand words, painting the country’s free-wheeling descent into its current, as it seems to many, deplorable state.

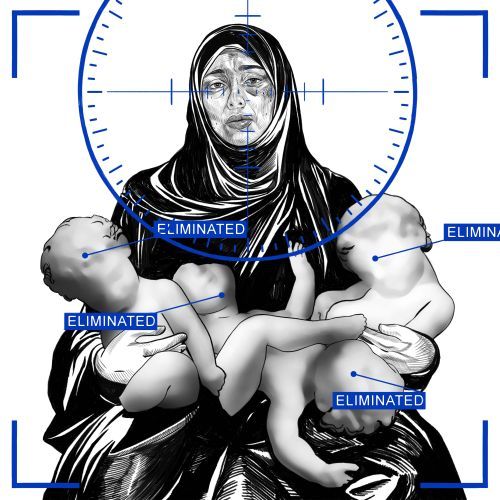

“Make war not love”

The ruling AK Parti, the Justice and Development Party, was established in 2001, and came to power in 2002. After 16 years in office, the higher echelons of this self-proclaimed non-confessional party, in their attempts to raise a “religious generation,” still confess, and complain about their failure to stamp their mark in the fields of culture and arts. As for television… well, that’s another story.

Tomris Giritlioğlu, a giant of a producer and an acclaimed director with more than a dozen mega hits under her belt, does not pull her punches: “Television is going through its worst period for as long as I have been around to bear witness.” Giritlioğlu has been around for the better part of the history of Turkish televisions. Her first production was in 1991, one year before the founding of the first private network.

A slide towards more conservative media ownership in the past decade has been accompanied by a deviation in the target audience, according to Giritlioğlu. The market does not favour projects that prompt the audience “to confront themselves, or historical facts.” Yet this is the raison d’être of TV, to her mind. The whole society has “changed its shell,” and became “devoutly religious,” in Giritlioğlu’s words, “and that change is perfectly visible on screens.”

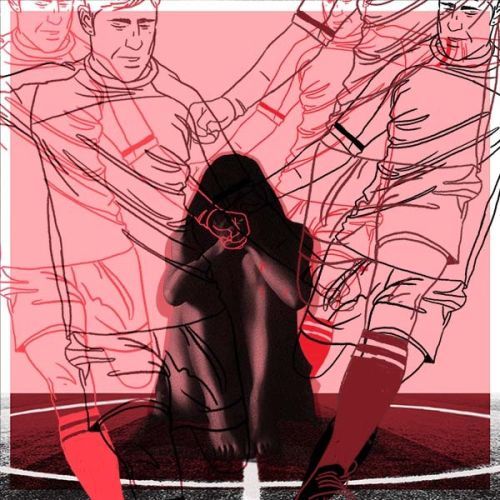

What’s left to show on TV? Apparently, a staunch Spartan life. Prof. Tayfun Atay, Director of Intercultural Dialogue and Studies Center at Okan University and an eminent critic on all things related to popular culture, emphasizes that as recently as five years ago, “the socio-cultural climate aggravated by none other than the sanctimonious ruling party” favoured affection on TVs, and inflicted penalties on violent content, only to reverse the trend later on. With the rising populism and ultra-nationalism, “the new normal on TVs is incitement to violence,” and, make war not love, is now the dominant trend.

“The very political culture that canonizes violence, that fethishizes warmaking, that ideolizes armament is now decisive and controlling over popular culture itself,” Atay writes, adding that “even though the ruling party could not come to power in culture and arts, as they so profess, this is their way of ‘holding dominion’ over popular culture.

There are repercussions. Turkey’s TV sector, exports dramatic series valued at $350 million per year, according to the government reports, with various shows becoming blockbusters in Latin America, Asia, and South Africa. The shared objective for the sector is to cross a $1 billion threshold in the five years to come. The Pit itself has already been sold in Georgia, Russia, and Chile, “with a lot of interest from the Middle Eastern countries,” according to Can Okan, CEO of Inter Medya that distributes the show globally. But first, the sector has to jump through hoops set by RTÜK.

This year’s global showcase at Cannes revealed a staggering zero interest in newly-produced Turkish shows. That, in itself, is an indicator of RTÜK’s overwhelming and detrimental control over the sector, as a legitimate censorship mechanism, according to Prof. Tayfun Atay. Adding insult to injury, the government recently passed a law expanding the authority of RTÜK, giving it powers to regulate and monitor every kind of online sound and visual broadcasting.

When all is said and done, the Pit accomplished one thing. Shortly after the “kiss” incident, the drama showed the endearing couple, Yamaç and Sena endeavoring to keep their hands off each other. Yamaç, with his devilish charm, leans in to kiss Sena passionately, when at the last moment he pulls back, and says: “I would kiss you now, but I can’t.” To which, Sena, taking her cue from Brecht breaks the fourth wall. Gesturing to the audience she responds: “They would punish us.”

When the facts are stacked against us it might be fiction that comes to the rescue.