Friendship and longevity and dying species

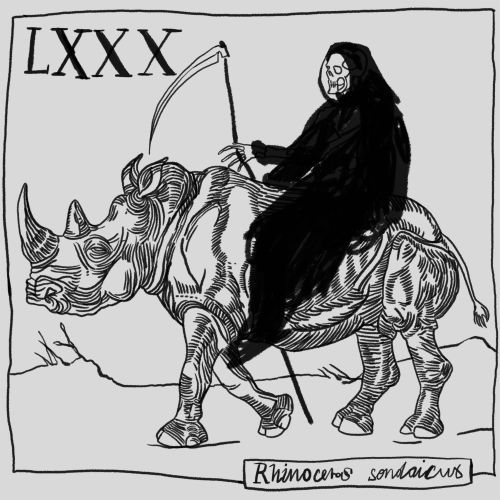

Adders in the United Kingdom could become extinct within 12 years. That may be the impact of around 57 million pheasants and partridges that are released each year across Britain as game birds. Before becoming prey for hunters, many of the birds disperse within the country, including in protected areas. They kill reptiles, including adders. A recent survey suggested that the only venomous snake in the country may die off by 2032.

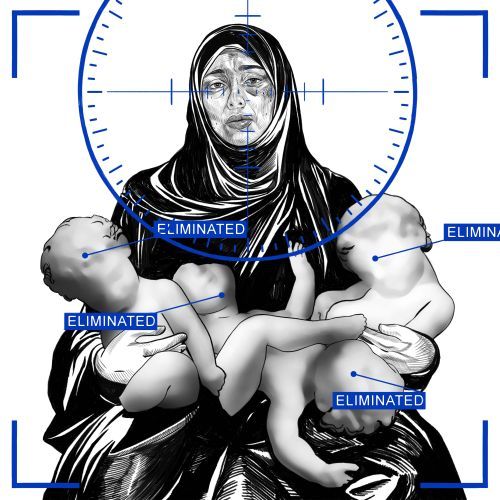

Between 1970 and 2016, we lost 68% of the monitored population of wild mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish, according to a report by the World Wild Fund. The decline was the highest in tropical subregions (around 94%) and the lowest in Europe and some parts of Asia (around 24%). We could slow down the loss of biodiversity – as the authors of the report write – by more conservation efforts, integrated with changes in food production and consumption patterns.

Many species, humans included, live longer if they have friends. So do baboons. Data from the continuous observation of baboons in Kenya since 1971 helped scientists in research which showed a longer lifespan in both males and females who had friendship-like relationships. Male baboons benefited from having more female friends – even if they didn’t mate with them. Meanwhile, the more dominant, “alpha” males lived shorter.