The impact of the gold rush in Zimbabwe and Somaliland

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, the work of artisanal miners and small-scale gold prospectors is the world’s largest source of mercury pollution. Gold prospectors from the Odzi River near the town of Mutare in Zimbabwe – unregistered artisanal miners – sift rocks from the river bed and colour the sediment with drops of mercury that sticks to the gold. Then, they use fire to separate the two metals. There are around 500,000 such unlicensed miners in Zimbabwe, supplying more than 60% of the gold mined in the country. It is Zimbabwe’s number one export commodity of critical importance to the crisis-ridden economy – in 2020, profits from the sale of this metal bullion amounted to US$2.14 billion.

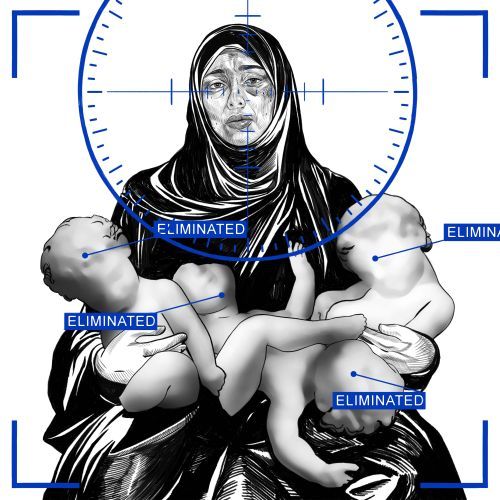

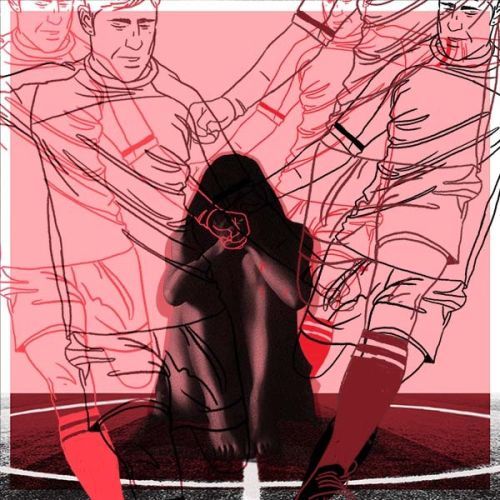

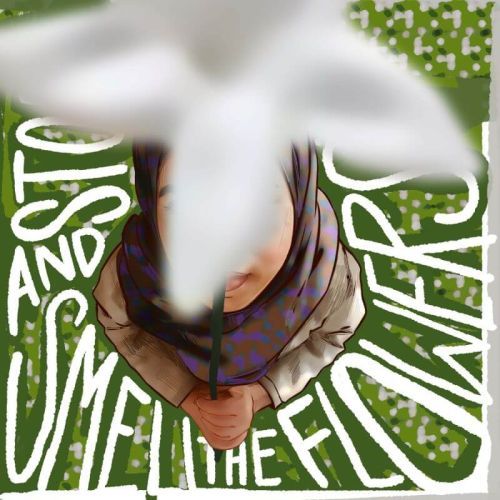

The gold rush in Somaliland – an Islamic republic not recognised by the international community – threatens the frankincense and myrrh perfume trade, which has existed since ancient times, and the supply of frankincense to temples worldwide. The people of this region have been exporting gold, frankincense and myrrh for thousands of years. In recent years, however, prospectors for the precious metal have been destroying the vegetation by clearing areas for mining and digging deep into the ground. In this way, the perennial trees of frankincense (whose resin, called olibanum, is used to make frankincense) and Commiphora (whose resin is myrrh) are dying. Gold mining also means other problems: drug addiction among the miners, the presence of the Islamist terrorist groups Ash-Shabab and Somali IS, feuds between family clans, or school closures due to the involvement of teachers and students in the local gold rush.