It was meant to be a show of might, a showcase of Turkey’s economic status under the rule of the Justice and Development Party (AKP). The size and capacity of Istanbul’s new airport were designed to make Heathrow look small, Charles de Gaulle blush with embarrassment and O’Hare turn green with envy. From groundbreaking ceremony to the first take-off in a record-breaking four years, it was supposed to be a bravura display of Turkey’s construction prowess.

A display it has been, but not of a flattering kind. The mega project, expected to become the world’s largest airport by physical size when all phases are completed, was controversially built in one of Istanbul’s most important green belts. More than 2 million trees were cut down in defiance of environmental concern. Moreover,

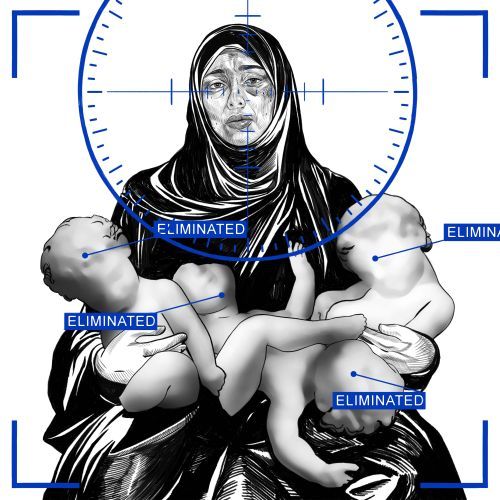

it was less a display of Turkey sophisticated construction sector than how that industry disregards workers’ safety. The unofficial tally is 400 work fatalities – making it less a construction site than, what some have dubbed, “the world’s largest concentration camp.”

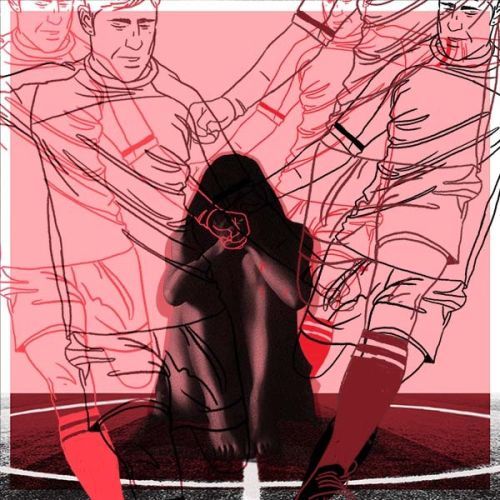

Workers have endured these harsh conditions in silence – until now. On September 14 and with less than two months before the planned grand opening, a group of workers launched a strike to protest safety conditions after a shuttle bus accident injured 17 people. For some workers, the demands were no more complicated than the “reimbursement of six months unpaid salaries.” They also insisted on “regular cleaning of sleeping quarters and toilets,” “an end to bed bugs,” “better food” or “distribution of work uniforms.” The strikers chanted, “we are not slaves”, called for dignity and an end to ruthless exploitation. The most pertinent demand was “doing something about workplace fatalities.”

Officials responded the same way as they have been responding to peaceful demonstrations for years: Using tear gas and arresting a massive number of people. More than 400 workers were taken under custody overnight on September 15, according to the Istanbul governor. A demonstration in Kadıköy, the Asian hub on the opposite end of the city, calling for the release of the airport workers, saw protesters themselves detained.

The head of Dev Yapı-İs Union, Özgür Karabulut, said the airport operator IGA gave verbal assurances of better conditions but, as if to contradict, added: “most had to go to return to work under pressure and under threat.” Contractors are responding to pressure to complete work before Turkey’s National Day on October 29. It has been celebrated in recent years with President Tayyip Erdoğan cutting the ribbon on the country’s latest big construction project. This ritual has become sacrosanct – and take precedence over engineering requirements, safety regulations or, as may turn out to be the case, the ability of passengers to make it to the check-in-counter on time. The underground metro along the shores of the Black Sea, connecting the airport to the city’s transport grid, will not be completed for another year.

Workers accused of “treason”

Opening a new airport by October 29 is no small feat. It involves shutting down the existing Atatürk airport since the two cannot operate simultaneously without creating a safety hazard over shared airspace. Two months is a very short time to put a myriad of final details in place—let alone test them. According to Karabulut, it would take at least to more months to complete the works. The clock is ticking.

The tension among officials is palpable. Recrimination and allocating blame have already begun. Istanbul Governor Vasıp Şahin said the workers who were detained were guilty of “provoking others.” Some pro-government pundits even went as far as suggesting that students had mixed in the crowd of workers and the protest was akin to “treason”. Fatih Altaylı, a senior columnist, questioned why workers who never complained for four years have started protesting “five weeks before the opening.”

If this sounds like a conspiracy theory, it is not the first to involve the new airport. In 2013, an economic advisor to Erdoğan, Yiğit Bulut, said that the massive Gezi protests were a plot engineered by the German airline, Lufthansa, to prevent millions of passengers deserting Frankfurt.

From the outset, it was clear government was determined to use the new airport as a positive PR tool; anything unfavourable was not going to be tolerated. Expert reports that the airport’s location would interfere with the path of migratory birds were binned. Concern for the impact of so massive felling of trees on Istanbul’s climate was brushed off. Daily reports of workplace deaths were denied.

The airport is built by a consortium of five Turkish construction companies, including firms always favoured in government tenders such as Cengiz, Kalyon and Limak, with a 25-year rent agreement for more than one billion euros annually. The rent agreement brings its pressures: The early the airport starts operating, the sooner they can generate profit. Much of the construction work, as is often the case in Turkey, has been subcontracted. Subcontractors acting on low margins try to slash labour costs in turn.

Those who hope Istanbul’s new airport will demonstrate Turkey’s strength are showcasing precisely the weaknesses they are trying to hide. The mega project clearly shows the authorities’ disregard for norms and regulations, for the environment, for safety, for labour rights, for freedom of information and for dialogue with citizens. In a sense, the airport is an excellent reflection of Turkey under Erdoğan era. Only a few countries would have been able to build such an airport in such a record time and by allowing such little debate. Turkey is in that top flight.

Photo: Workers have protested the labour conditions at the new airport, due to open on October 29.