More than 650,000 of Venezuela’s 31 million citizens left their country last year because of the deteriorating economic situation. Most of them emigrated to Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, the United States, Panama, Mexico, Spain, Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica. It is expected that this year the number will rise even further – research done in the country says that four out of ten people consider going abroad.

Only a few of them have visas.

It is estimated that more than two million Venezuelans live abroad (including half a million in neighboring Colombia, 80% of whom do not have visas). For some of them, Colombia is the final destination, others are looking for ways to relocate to other countries.

The increase in the number of emigrants is impacted by the deteriorating economic and political situation in Venezuela. The country is struggling with a recession, unemployment and growing inflation. Thanks to its oil resources, Venezuela used to be one of the richest countries in Latin America. After the death of the socialist President Hugo Chavez, Nicolás Maduro took over the power and continued the policy of his predecessor. At the beginning of April 2017, mass protests took place against the president and Venezuela’s sinking economy. Dozens of people were killed as a result.

The price of oil dropped significantly and so have Venezuela’s proceeds from its export. The stores began to run out of basic food products and the currency kept losing value. Because of the above, last year a total of 1.3 million citizens of Venezuela crossed the border with Colombia. Some wanted to stock up on food, clothes and medicines. Others tried to smuggle petrol and drugs. The border guards observed that many Venezuelans stated that they were coming to Colombia as tourists while in fact their actual goal was to take up illegal work. To avoid deportation, they came back within three months. After a while, they returned to work in Colombia again. “It is the biggest wave of immigrants that has ever come to our country. Up until recently, we officially had 110,000 emigrants”, says Christian Krüger, the director of the immigration office in Colombia.

Without a plan for life

Luis Madrid, a psychiatrist and coordinator of a Committee for Affective Disorders in Venezuela admits that he is approached by more and more people who are scared by the prospect of emigration.

“The real exodus started around four years ago. People who emigrate today do it in a chaotic way; without a plan and that increases the chances that the migration will not be successful”, he says.

He admits that this reality is new for the Venezuelans who, a few years ago, didn’t have to think about finding jobs abroad. This is why only a few of them have plans for what’s going to happen after they leave Venezuela. Despite that, even the ones who are prepared are full of doubts. “They have to leave even though don’t want to. Their fear manifests as anxiety and panic attacks. Some of them have children or families abroad who are asking them to come and promise to take care of them. There are also those who go without a plan, saying, “I’ll see what I’ll be doing”. It is common. Others have small children and want to provide better education for them. I also have patients who have sold all their belongings here, left the country and now are back.

They sleep and wash themselves on the street

The influx of such a number of Venezuelan emigrants is a new phenomenon for the Colombian government as the flow of migration for years used to go the other way. It is estimated that until the crisis, over one and a half million Colombians lived in Venezuela. Now the government of Juan Manuel Santos hopes that in the near future most of them will return with their families to the former homeland. However, the Venezuelans are not treated as foreigners. It’s mostly illegal immigrants who pose a challenge for the authorities.

“Some Venezuelan people are not here legally but you can’t forget that the Colombians travelled there and worked in various sectors so now we can’t turn our back on our neighbours”, says Krüger. “We should behave humanely towards the people who are in need of our support but we also have to follow the rules”, he added.

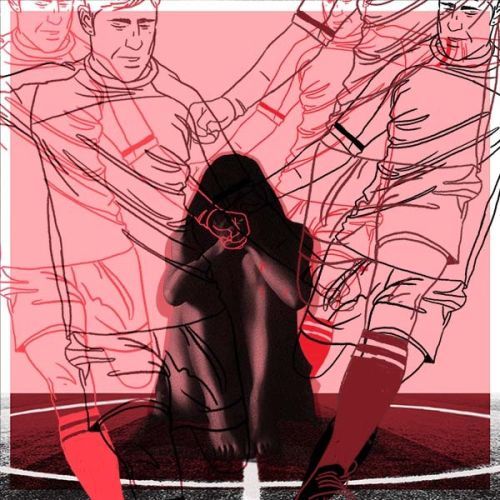

Daniel Pages, president of the Association of Venezuelans in Colombia, claims that the situation is much more complex, as the recent immigrants are often people with no means to live. Due to the lack of prospects, some of them sleep on the streets or resort to prostitution to provide for their children. People who don’t have legal employment (or a job permit), have no other choice. Pages believes that they should be able to work here, they can’t be marginalized.

At the beginning of January 2018, the Colombian authorities ordered 400 Venezuelans to leave the bus parking lot in Barranquilla. Some of them have urinated and defecated on the street running next to the restaurant and washed themselves in a stream of water leaking from a ruptured pipe.

“We have witnessed situations that have affected passengers, traders and people working at the bus station. Prostitution, drug trade and fights happened here”, says Devin Silva Llinás, one of the employees.

Social risk in Brazil

In December the authorities of the border state of Roraima in Brazil announced that the large number of Venezuelans who have crossed the border may pose a social risk. In the last two years, more than 30,000 expatriates from that country arrived in Brazil. Most of them are under 30 and about 35% are studying or have higher education. Only a few have found places in the overcrowded refugee camps. The rest, due to the difficult financial situation, are out on the streets. The emigrants are trying to get visas and look for a job. To survive, they sell vegetables on the streets, wash car windshields, some resort to prostitution. ”We have a big problem that will only grow”, said Teresa Surita, the mayor of the state capital, Boa Vista. She points out that the schools in Boa Vista have admitted almost 1000 children from Venezuela and the hospitals are running out of beds, due to an increased number of patients (some of them are Venezuelan pregnant women).

Temporary residence permit

Other countries also need to learn to function in the new reality. For instance – around 6,000 Venezuelans are currently living in Peru. The government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski announced that every Venezuelan who will come to Peru by the end of 2018, will get a temporary residence permit. The only condition is to have a passport, fill out the application form, pay the visa fee and have no criminal record. A lot more people emigrate to Argentina. Last year over 27,000 people ended up there there, which is 15 times more than in 2014.

“I think that this year 35,000 of my countrymen may come here”, says Vincenzo Pensa, president of the Association of Venezuelans in Argentina. He admits that many of them at the beginning work on the black market, mostly in food service. That, in turn, makes it difficult for them to rent a flat. Up until recently, the first emigrants have brought their families with them only after they have stabilized their situation. Now whole families flee the country as they don’t know what is going to happen in Venezuela. “The situation there is very tense and volatile”, adds Pensa.