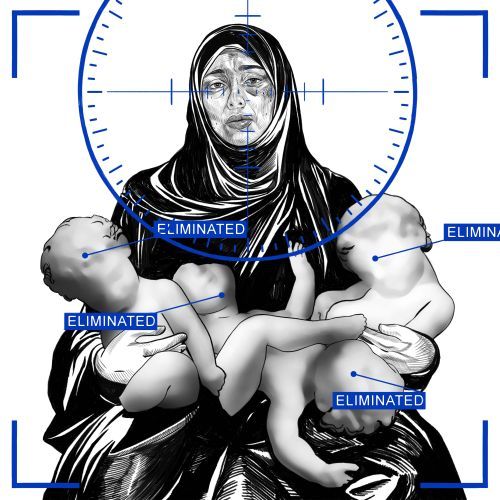

When asked what was more difficult, being a Turkish football player in Germany or a Kurdish player in Turkey, Deniz Naki didn’t hesitate. “Of course, being a Kurd and Alevi [a dissident branch of Islam whose members tend to social liberals] in Turkey,” said the footballer who played both for St Pauli in Hamburg and Amed Sportif in the southeastern Turkish city of Diyarbakır.

“Sure – there are Neo-Nazis in Germany, but nobody likes them,” he added. Like his more famous colleague, Arsenal’s Mesut Özil, Naki was born in Germany to immigrant parents. Their lives took different paths, but they managed to arrive at the same destination: disenchantment with the way football is run.

Özil’s announced his retirement from the German national team after denouncing “racism and disrespect” which greeted his photo op with Turkish President Tayyip Erdoğan. If Turkey was nursing a bruised ego after failing to qualify for the World Cup, it was in part salved by a player who, despite choosing to play for Germany over Turkey years ago, was still prepared to sacrifice his international career out of “loyalty” to his country of descent. It certainly flattered Turkish football fans’ patriotism and gave their government a stick to beat what they called Germany’s horrific racism.

“What Mesut Özil went through and how he was treated is unforgivable,” scolded Gülnur Aybet, an academic and recently appointed senior adviser to Erdoğan. “There is NO excuse for racism and discrimination,” she tweeted. Fair enough, one would be tempted to think. Yet what Naki went through and how he was treated in Turkey was also unforgivable. As Prof Aybet said there, racism and discrimination can never be excused.

Naki’s family came to Germany from another eastern province, officially called Tunceli but known locally by the historical name of Dersim. After a brief spell in Germany’s famously anti-fascist club St Pauli, Naki spent most of his career in Turkey. A talented midfield player, Naki surprisingly rejected many more lucrative offers with the big Turkish clubs to Amed Sportif in the third division. As an outspoken Kurd and Alevi, he made the deliberate political choice to pursue his career in a team based in Diyarbakır which embraced its Kurdish identity.

Banned over call for peace

Amed Sportif was a team founded by the municipality, which was then run by a pro-Kurdish party. In 2014, it called itself after the Kurdish name for Diyarbakır. This symbolic gesture greatly appealed to supporters, and the club quickly drew large crowds to their games. Amed Sportif was gaining momentum while the city’s former leading club, Diyarbakırspor, which once competed in the top flight, was shuttered due to bankruptcy. With a tattoo reading “Azadî” – meaning “freedom” in Kurdish – in one arm and “Dersim 62” on the other, about the name of his hometown long banned by the Turkish state, Naki quickly became an icon.

He tried to become a peacemaker as well. In 2016 Diyarbakır was the scene of bloody conflict as after military operations affecting the entire region. The old walled city was almost entirely destroyed after the months-long siege, and this prompted Naki to call to for an end to the conflict after a cup match. “I want people not to die. I want peace. We don’t have any other choice than to call for peace,” he said.

This comment earned him a record 12 games ban. However, that was just the start of his troubles. He also received a suspended prison sentence of 1.5 years on charges of “propaganda for a terrorist organisation” by a court in Diyarbakır over the same statement.

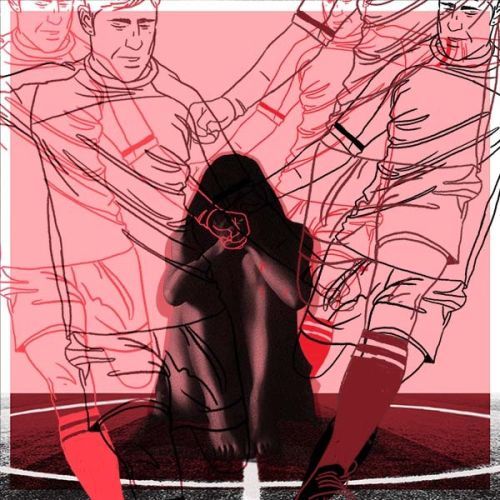

The club had an unexpectedly successful run at the cup and were the underdogs against Bursaspor in the last 16. They won that tie but not without facing sustained racist chants – broadcast live to the nation. The team lost their quarter-final to Fenerbahçe, but it was a pyrrhic victory of sorts in which they displayed a banner “Children should not die, they should come to the match” before the game.

From then on, racist chants became routine whenever Amed hit the road. Naki was violently attacked on the pitch during a game in Mersin. He remained outspoken, especially in social media, where he was a regular fixture. However, he was a marked man. When he returned to Germany during the winter break earlier in 2018 – he escaped unharmed an armed assault on his life while driving on a motorway. Two bullets fired from a black van hit his car. Naki said he believed the attacker was either a Turkish government agent or a right-wing Turkish radical. He decided not to go back to Turkey and ended his contract with Amedspor.

It was bound to happen eventually. Only a few days later the Turkish Football Federation banned him from all football games for 3.5 years, an unprecedented punishment for supposed “discrimination and ideologic propaganda”. According to Turkish football regulations, any ban over three years is a ban for life from professional football. The decision meant that Naki would never be able to play again in Turkey.

In a statement issued after Özil accused the German Football Federation of discrimination, Naki appealed to him to be more sensitive about racism towards Kurdish football players in Turkey. Naki said he was also “lynched repeatedly” for posing with Selahattin Demirtaş, the jailed former co-chair of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). “Why those who supported your Turkishness didn’t accept my Kurdish roots?” Naki asked. It is a question Özil might have raised when posing for a photo with the person best placed to answer.

Photo: Mesut Özil while playing for Germany at the 2018 World Cup (L) and Deniz Naki during an Amed Sportif game (R).