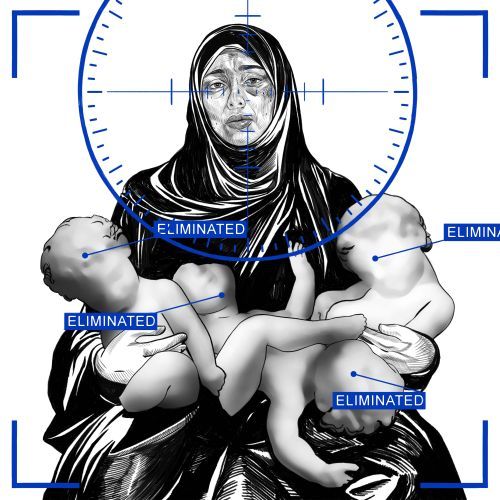

Guilty as (not yet) charged: Civil society activist jailed without trial for over 300 days

Did he really commit a crime or was it simply, as most suspect, his turn to go to jail? Businessman Osman Kavala is known for his generous support to Turkey’s civil society and art world. Without his support, so many cultural initiatives would never have seen the light. But not everyone sees it that way. He has been under detention for more than 300 days, and yet the prosecutor has still to produce an indictment. He has become a symbol of arbitrary justice in Turkey’s new regime.

Certainly, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is not convinced of his innocence. He labelled Kavala “Turkey’s Soros”, an obvious reference to the Hungarian-American business magnate and philanthropist whose name is often invoked to a hidden agenda to undermine the regime.

On Monday, August 27, artists and cultural workers gathered at DEPO, one of Istanbul’s leading cultural institutions founded by Kavala, to protest against his imprisonment. They held banners bearing the messages “We miss you” and “Osman Kavala – 300 Days Behind Bars. Another group gathered in front of the Silivri Prison, on the outskirts of Istanbul. As they did on the 100th day of his imprisonment. And the 200th day.

This spontaneous show of concern is Osman Kavala’s reward for his selfless aid to civil society. The question he always asks is “How can I help?” He directly funds projects and connects people with one other. His interest in literature and the arts dates from the early 1980s when fresh out of university he helped found one of Turkey’s most important publishing houses, İletişim home to some of Turkey’s most important social scientists and now publisher of Nobel winner Orhan Pamuk. The Anadolu Kültür and Diyarbakır Arts Center were initiatives to promote the arts outside of Istanbul. He is also a founding member, board member and on the advisory board of many civil society organisations such as Open Society Foundation, Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV), the History Foundation or the environmental NGO TEMA Foundation. The list goes on. He created DEPO, a non-profit cultural centre with an emphasis on minority culture.

And for all that he is famously unassuming. You can bump into him at coffee at a LGBTİ+ meeting, shirt-tail out, strolling down the street or hidden in the throng, having a glass at one his exhibitions. Not the sort of person you might think who poses a threat to the safety of the realm.

But according to Turkey’s President and head of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), Kavala is guilty as (not yet) charged. At a meeting of MPs a few days after Kavala’s arrest, Erdogan criticised him and his supporters. “Some try to deflect the truth by means of praises attributed to him such as ‘He was a good citizen, a media member, an NGO representative,’” Erdogan said, before claiming that Kavala played a part during the massive Gezi protests in Istanbul’s Taksim area in 2013. “The identity of this figure called ‘the Soros of Turkey’ has been uncovered. That was his name that came up in the [U.S.] Consulate General [investigation]. All connections have surfaced. And it’s the same person behind the incidents in Taksim. You see again the same people behind funds transfer to certain places. Who are you trying to fool?”

Imprisonment as a means of punishment

Osman Kavala was taken into custody in the evening hours on October 18, 2017, at Istanbul Atatürk Airport as he was returning from a meeting of a project planned to be realised in cooperation with Goethe Institute in the southeastern city of Gaziantep. The news was shocking but at the same time not quite a surprise. In retrospect, it was just “his turn” – an example to discourage others in the world of business for trying to promote social change.

After the coup attempt of July 15, 2016, opposition groups had increasingly been targeted by the pro-government media and the judiciary. Kavala was one of the people who were marked. Following his detention, Kavala was immediately targeted by the pro-government newspapers. Some nationalist and leftist news organisations were equally triumphant, critical of Kavala’s international connections.

Even the mainstream opposition has an ambiguous stance when it comes to civil society. Muharrem İnce, the leading opposition candidate who came second best with 31 per cent of the votes during the presidential elections on June 24, criticised what he described as a lack of reaction from civil society leaders regarding the move to a strong presidential system. “Where are our intellectuals who are the ‘Champions of Participation’ and renowned civil society institutions who fund their projects with European funds?” he tweeted. “What do our self-proclaimed republican intellectuals say about deactivation of Parliament?”

The answer is that after Kavala’s arrest many were scared.

Without an indictment, we still do not know the specific nature of his presumed offence. Nearly ten months in prison, he has yet to appear in court. It is the gravity of the unknown charges – a vague accusation of attempting to overthrow the constitutional order which is being used to keep in pre-trial detention. “I am waiting for the day when I will be able to defend myself in court and see the face of justice,” wrote Kavala from prison last month.

The Turkish judiciary has a long history of relying on lengthy detentions as a means of punishment. The country has faced many pecuniary penalties by European Court of Human Rights. According to an emergency decree issued last year, the period of pre-trial detention can be extended up to seven years. Kavala lodged an application to the European Court of Human Rights against his detention. “While the right to apply to the ECtHR is reassuring, it is painful to declare that the country of which you are a citizen does not value your freedom,” he wrote.

Warning for civil society

It is hard not to conclude that Kavala’s imprisonment has little to do with law and everything to do with politics. We have seen similar cases with the detention of German journalist Deniz Yücel and Amnesty Turkey’s chairman Taner Kılıç. They were bargaining chips in Turkey’s international relations and now are released. Kavala’s imprisonment is a sword of Damocles hanging above civil society activists whom might be tempted to involved in the protest. At the same time, it is a warning to the business community to behave.

But there is hope. Kavala’s name was mentioned in a recent article for Hürriyet newspaper by the pro-government columnist Abdülkadir Selvi. Instead of pressing for his conviction, he talked about his potential release. Turkey now under international siege might need a gesture to convince the European Union to get relations back on track. Selvi, who has sources close to the government, was speaking after something called the Reform Action Group met for the first time after three years. “Remove the obstacles of freedom of expression and media. End the imprisonment of symbolic names,” Selvi wrote.

Until that happens, Osman Kavala will be sorely missed.

Photo: Artists and cultural workers gather in front of the DEPO cultural centre in Istanbul to mark the 300th day of Osman Kavala’s imprisonment and call for his immediate release.