For those of us once laboured in the bowels of Turkey’s legacy media, the sale of the country’s largest print and television group has sent a shiver of Schadenfreude down our spines. It is, as we old duffers like to say, “the end of an era,” although in our franker moments we confess that era was far from glorious. I, for one, find it hard to be all that nostalgic about the time some 20 years ago when my wife successfully sued Hürriyet, the group’s flagship paper, for calling her a thief.

It did so almost certainly at the behest of national intelligence, upset at my reporting for CNN, in an effort to encourage us to pack our bags and leave. However, with the passage of time I have come to realise that while the Doğan Media Group might have been run by a motley crew, they were (as the Turkish would have it) “our motley crew” and we may yet miss them now that they are gone.

We still do not know what arms were twisted to force the sale of a slew of popular titles including the tabloid Posta, a sports daily paper called Fanatik and television stations like Kanal D and CNN Türk. Nor do we know how the rival Demirören Group was persuaded to cough up a reported $1.1b (including debt) to get their hands on what in all probability will be a declining asset (Hürriyet is worth a quarter of what it was in 2006). However, we do know — or strongly suspect– that Demirören does not actually like owning newspapers. This knowledge comes from a 2014 phone conversation leaked onto YouTube between then prime minister Tayyip Erdoğan and Erdoğan Demirören, the elderly patriarch who presides over the energy-to-construction conglomerate that bears his name. Mr. Demirören is in tears as he receives a brutal dressing down for a story that appeared in his Milliyet newspaper (also purchased from the Doğan Group back in 2011) that had the temerity to embarrass the government. “How did I ever get into this business,” he sobs. A short time later, Milliyet forced the dismissal of its lead columnist, Hasan Cemal, for his public defence Of a decision to print the piece. After all embarrassing governments is just the sort of thing newspapers do.

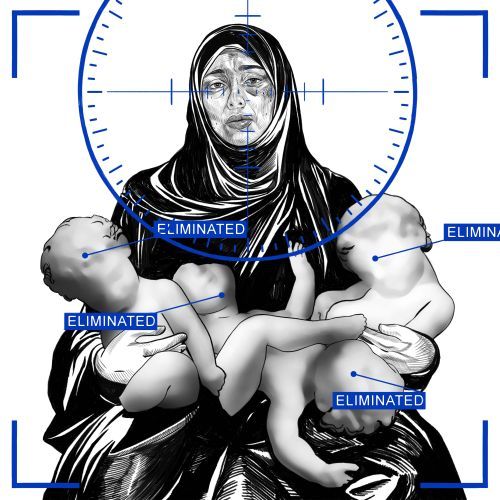

Or used to do. We are at least pretty certain why the sale of the Doğan media empire took place. Turkey is entering an election cycle, with snap presidential and parliamentary elections taking place on the 24th of June. The government seems determined that only its version of events will be heard.

Their methods are not too subtle. This 3rd of May we marked the International Press Freedom Day with some 175 journalists behind bars. Only last week the courts convicted over a dozen staff from the principal opposition paper Cumhuriyet on the surreal charge of “aiding a terrorist organization without being its member.” Sentences ranged from 30 months to 7.5 years and included the paper’s editor-in- chief, Murat Sabuncu and outspoken reporter

Ahmet Şık. The only silver lining is that the convicted have been released from jail and are pending an appeal.

Yet while there has been a clampdown on dissenting media, the Doğan publications have been a bit more difficult to control. True, the tax authorities did put a damper on the group’s eagerness to speak out in 2009 with a threatened $3.3b tax fine on the parent company — equal to its market capital. But on the whole, the Doğan group understood the art of the possible, when to give a wink and when a nod. Yet, it also understood that in order to extract favours from the government, every now and then, it had to show real muscle and pull the tiger’s tail. There was no commercial advantage of being in the government’s pocket all the time.

If I had to define the difference between the Doğan era and today’s brave new world it would be thus: The group’s founder, Aydın Doğan managed to parley his acquisition of Milliyet from being the owner of a chain of car showrooms to being one of Turkey’s biggest tycoons. And if his publications were sometimes guilty of peddling influence, at least they understood the need to have some influence to pedal. Even the most crooked policemen knows he has to enforce the law part of the time. Likewise, the Doğan group understood what it was the time to do real journalism.

The new generation of Turkish press barons, by contrast, don’t acquire media to put pressure on the government or leverage influence. They don’t have to. Owning newsprint and television is a sort of a tax on the business they already obtain through government grace and favour, a loss-leader for their non-press interests. They become media proprietors to appease. It’s enough to make a grown man cry.