Incompetence doesn’t really matter. Until it does. The quality of democratic institutions doesn’t really affect international investment. Until it does– that is until the wheels of government institutions become so sticky and clogged that they threaten to come of their axles altogether.

Look at the press freedom or democracy indexes of organisations like Freedom House or Reporters Sans Frontières, and Turkey in the last few years has been sinking like a stone. Yet up until now voters have been prepared to tolerate an erosion of basic liberties in the name of economic efficiency. Supporters consoled themselves that at least the government knew how to manage the economy. And while everyone is aware that there is a new got-rich-quick cohort of AKP cronies, people tell themselves that at least the roads were getting built.

The index with which no one is able to take issue is the exchange rate of the lira against the dollar and this too has been falling fast in the last weeks and months. Only a dramatic intervention by the Central Bank to raise interest rates a full three points was able to arrest a 9 percent fall in the exchange rate of the previous two days. The currency which had been worth some 3.8 to the dollar at the end of March was nudging 5 to the dollar before the Central Bank intervention. And even this has been characterised as “too little too late” by many analysts who anticipate another rate rise to deal with a rate of inflation which might exceed 12 percent.

This is terrible news for heavily borrowed Turkish corporates as well as ordinary householders. Turkey will vote again this 24 June at joint presidential and parliamentary elections. Will voters suspect that sacrificing freedoms means sacrificing prosperity as well?

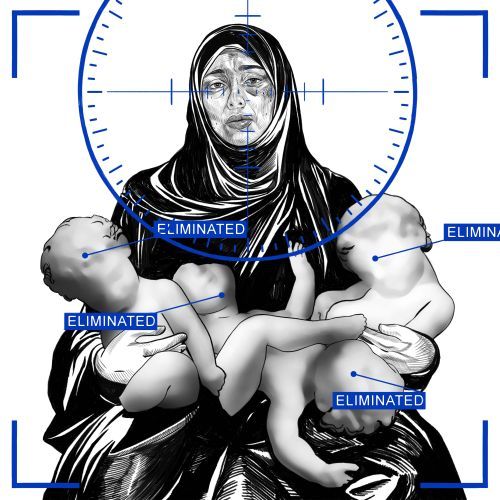

The economy began to go pear-shaped radically around the time the rating agency Standard & Poor’s downgraded Turkey further into junk in an unscheduled 1 May report. Among the factors cited for the decision was the failure of a lower court to implement the ruling of the Constitutional Court to release two journalists in pre-trial detention (one of whom has now been released, the other sentenced to aggravated life in prison). Commentators point to an increasingly arbitrary disregard for rule of law as Turkey still lingers under emergency rule – imposed after the failed 2016 military coup and without an end in sight.

But the knockout blow to market confidence came when President Erdoğan said in an interview with Bloomberg Television that he, not the Central Bank, was ultimately accountable for monetary policy and that keeping interest rates low was intentional. Traders, already alarmed at the pre-election by the pork-barrelling the government was using to buy support, looked for the exit and then began to run.

Investors are like small children, economists tell us, in as much as they like a story. And until recently the Turkish story went like this:

- The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) did not come to power in 2002 because Turkey was in the throes of a religious revival and wanted a party that would fight the secularist old guard. Rather they did so because the old guard had fully bankrupted the country, funding the political machine through unsustainable levels of debt and a huge rate of inflation

- Thus, the AK Party, was not an anti-Western, anti-market political force. The government it formed understood the need to restore credibility and initiate reforms. In 2005, Turkey for the first time completed an IMF standby programme—having failed the previous 17 times!

- After a third of GDP was wiped out in the 2001 crisis, Turkey managed to rebuild a strong banking sector. Turkey came leaping out of the Lehman Brothers crisis with GDP rising by 8.5% in 2010, 11.5% in 2011. It had recovered from the crisis a decade earlier and was now poised for a “second generation” of deeper structural reform.

This second generation – the result of education, a restructuring of the labour force, a focus on productivity rather than consumer led growth—was of course more difficult to implement and called for political risks the government loathed to take. - Yet the market retained faith in AKP management. It dismissed as rhetoric for domestic consumption, the loopier notions coming from the top that “high interest rates caused inflation” – orthodoxy has it that it’s the other way round– or that Turkish economic setbacks were the work of foreign powers jealous of Turkey’s success.

- Even then, there were worries that the AKP was going to spend its way through the current electoral cycle (there will be important municipal elections next spring) and that the government’s ability to muddle through would be tested to the full. Investors were still happier with the Erdoğan devil they knew than untested opposition parties whose own economic promises were equally populist in tone.

That Bloomberg television interview changed the story. The president was beating his “low interest rate” drum not to rally untutored domestic support but to convince international investors that Turkey could spend its way out of its current impasse. This made no sense. Turkey needs to borrow from abroad to tick over. Its current account deficit ($40-50b) is high among its peers, and it needs to turn over an additional $185b in short term debt.

In times of confidence or when there is high global liquidity, debt is not a problem. But these are not those times. A falling exchange rate or more costly borrowing are equally bad news.

The AKP calculation can still prove that the Turkish electorate has yet to reach that uncomfortable moment when it accepts that the economy has run out of fuel. They may still give Tayyip Erdoğan the strongman presidency to which he has long aspired. And history’s lesson, however banal, may be that nations which slide down the slippery path towards autocracy don’t really suffer.

Until they do.

Photo: Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdoğan speaks to Bloomberg TV’s Guy Johnson in a televised interview at Bloomberg’s London Headquarters, 15 May 2018.