377. The Law on which the Sun Never Set

By Lola García-Ajofrín (about Sri Lanka) and De Lovie Kwagala (about Uganda)

In the 19th century, the British brought the so called ‘sodomy law’ to all its colonies. 161 years later, LGBTIQ+ community in some 30 countries still fights to Repeal It.

In 2021, there are at least 68 countries where same-sex sexual relations are illegal. More than half of those countries have one thing in common – once they were British colonies. Their penal codes include crimes under the label of “unnatural offences” that were first introduced by colonizers into the Indian Penal Code in 1860 under Section 377 and then across the British Empire.

In the early 1920s, it was said that “the sun never sets” on Britain's lands, because when it was noon in London, it was midnight on the island of Fiji, which was a British colony until 1970. Britain began its first attempt to establish overseas settlements in the 16th century. Expansion accelerated during the 17th and 18th century driven by maritime competition with France. By 1920, it covered approximately one-quarter of the Earth's total land area, including over 80 nations.

Most of those countries gained independence gradually during the early 20th century, and many of the remaining countries achieved independence following the end of the Second World War. ” However, in about thirty of those territories, an archaic colonial law remained: Section 377 on "unnatural offences."

Section 377 does not explicitly refer to LGTB people. Still, it criminalizes what it called "unnatural" acts, including anal sex or sex with animals. It has been used as a tool to punish same-sex acts for a century and a half – in countries as distant and disparate as parts of the Caribbean, East Africa or Southeast Asia.

From Asia to Africa or the Caribbean

Section 377 was introduced by British colonizers into the Indian Penal Code in 1860 and then across British Empire. “It was at the heart of the British colonizing project. Brits were seeking to subject people in its colonies not just to British control but also to British morality,” explains Neela Ghoshal, Associate Director in the LGBT Rights program at Human Rights Watch. “That law was a tool to control people’s bodies, to control people’s sexuality and get them in line with British morality, if not, they would be punished,” Ghosal continues.

It was not the only law that has been used in that kind of way. “There are a whole bunch of laws that are products of British colonization, a lot of them related to class politics, around things like vagrancy,” Neela Ghoshal continues.

One of the reasons these laws were not repealed after the independence of these countries from the British colony is because “they continue to serve the interest of governments even in post-colonial societies,” Ghosal concludes.

377 - When the Indian court quoted Shakspeare

Belize (2016), Trinidad and Tobago (2018) and India (2018) are the last former British colonies that abolished the homophobic colonial legacy from their criminal codes.

In 2018, in India, where it all began, the step was taken towards a historic sentence. India's Supreme Court repealed the colonial-era Section 377, quoting Shakespeare:

“What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet."

However, LGTBIQ+ communities in some thirty countries still fight to repeal the homophobic legacy from its penal codes.

This is the case in countries as far away as Uganda and Sri Lanka, among many others.

SECTIONS 365 & 365A IN SRI LANKA

Meet the LGBTIQ+ Community in Sri Lanka Who is Fighting Stigma, Suicides and Forced Marriages

On September 6, 2018, after a years-long battle of activists and lawyers, the Indian Supreme Court decriminalized same-sex consensual acts in India by repealing Section 377. In the neighbouring country, Sri Lanka, the LGBTIQ + community followed the event with expectation. Would the historic ruling set a precedent to remove the archaic colonial law from its penal code too?

In Colombo, Sri Lanka, a lawyer who had overcome several suicide attempts, a filmmaker who had broken social taboos and a retiree who had recently come out as a trans woman dreamed of a change for a little while that day.

BACKGROUND - A LAW FROM 1883

Sri Lankan penal code has some provisions of ‘copy and paste’ of Indian Section 377. They are Sections 365 and 365A on “unnatural offences,” which have been used to criminalize the LGBTIQ+ community for over a century. The Sri Lankan Penal Code was enacted in 1883 by British rulers. It is still in force a century and a half later despite Sri Lanka's independence from the British crown in 1948.

The British, who firstly enacted a section to criminalize sexual acts “against the order of nature” in India in 1860, replicated those provisions, sometimes with the same words, across all its colonies, including Sri Lanka.

Europeans occupied Sri Lanka for over 400 years. Portuguese (1505–1658), Dutch (1658–1796), and British (1815–1948). Some traces of the occupation remain.

WHAT ARE THE UNNATURAL OFFENCES?

The “unnatural offences” were enacted by British rulers on its colonies to impose puritanical Victorian morality and penalize acts “against the order of nature”, a wide concept that encompasses sex with animals, as well as other types of acts not intended to procreation, such as anal sex or fellatio. In Sri Lanka, these provisions provide for a penalty of up to ten years in prison. Even though they are rarely enforced, the criminalization of LGBTIQ+ people’s lives fuel discrimination and allows impunity for abuses and hate rhetoric against the community.

Additionally, another colonial law, the “Vagrants Ordinance”, which penalizes “every person behaving in a riotous or disorderly manner in any public street”, has been used to criminalize transgender people and sex workers even though the Sri Lankan Constitution should protect the Fundamental Right to Equality under Article 12.

LIVING UNDER SECTIONS 365 & 365A

The number of LGBTIQ+ people that have been arrested or convicted under “unnatural offences'' in recent years is unclear. HRW reported that in 2018 “police brought charges against at least nine men for “homosexuality” based on the data from a police performance report.

In addition, HRW and Equal Ground, a local NGO, recently reported that since 2017 Sri Lankan authorities have subjected at least seven people to forced physical examinations,including anal and vaginal examinations, aiming to provide proof of homosexual conduct.

THE PROGRESS & CHALLENGES

The United Nations has repeatedly urged Sri Lanka to amend the Penal Code. However, the recommendations have not been listed so far. On the contrary, section 365A on gross indecency was amended in 1995 to substitute “any male person” and expand it to lesbian.

There has just been some timid progress, such as the gender recognition certificate that allows transgender people to change their national identity Cards.

A STORY OF STIGMA, SHAM MARRIAGES & SUICIDES

How does a 19th-century law affect the lives of people in the 21st century?

Between 2019 and 2020, Outriders interviewed nine members of the LGBTIQ+ community in Sri Lanka. They are: the first trans lawyer in Sri Lanka who survived several suicide attempts; a Muslim doctor and father of a gay man who believes it is time to sit and talk about the social changes; a Buddhist lawyer reporting abuses; a Hindu and Tamil lesbian activist fighting the stigma against “a minority inside a minority”; a Christian gay man and founder of the first organization for gay people in the island; a filmmaker who broke a taboo by screening a triangle story in national cinemas or a 72-years old trans woman who came out after retirement.

They told us about stigma, sham marriages, suicides and arrests.

DAMITH

“Hiding is a kind of mental pressure”

On a couch in his house, surrounded by reports and documents, Damith Chandimal, a Buddhist man and human rights worker, explains that in recent years he has collected “numerous cases of suicides, arrests and abuse against LGTBIQ+ people in Sri Lanka.”

SUSANA

“I wanted to be the girl; I did not want to marry someone else”

In front of a mirror in her bedroom in Colombo, after turning off the hairdryer and making her eyes up with the skills that she learned from YouTube tutorials, Susana explains that when she retired as an accountant, she put the suit and tie in a closet, talked to her wife and came out as a trans woman. She had been struggling with her identity for nearly 70 years. Susana, 72, came out as a trans woman when she retired. She is still married to her wife, a Muslim woman.

VISAKESA CHANDRASEKARAM

“A lot of gay men are getting in a traditional heterosexual marriage in Sri Lanka”

Not only did he manage to bypass censorship, but all kinds of audiences liked his film. Filmmaker and human rights lawyer Visakesa Chandrasekaram pioneered by introducing for first time gay protagonists in a Sri Lankan movie, Frangipani (2014). The movie explores the cost of social and family approval in Sri Lankan society. It won several awards, including the Best Foreign Film Director at the 2015 Rio LGBT Film Festival.

SHERMAN & MANJU

“They can just come here and talk safely”

On the second floor, above a hairdresser, there is a rainbow flag on the wall. Outside you can hear the melody of motorcycles, tuk-tuks and the chirping of the birds. Sherman de Rose opens the door of a drop-in centre for the LGBT community in Colombo.

KIRUTHIKA

“There are anal and vaginal tests, which are a kind of harassment”

Kiruthika, 37, as a Hindu and Tamil woman, the largest minority in Sri Lanka, and a lesbian, describes herself “as a kind of minority within a minority.” We met after work. She shows a rose tattoo on her arm.

AZAD

“If we were an open society, we could have saved that boy”

“In the last few years, so many gay people have died in Sri Lanka, they can’t handle the pressure, the pressure of life, the pressure of the society against the culture, so many, young people,” says Azad Moulana, 45, while drinking a tea in a café in Colombo.

KHAUSALIA

“The first need is to decriminalize it”

“My concern is not about the law, it is about the stigma”, says Khausalia, a researcher and queer Srilankan woman. She says that her close friends know about her, but she did not come out as a queer person at the office or with her family members.

JOSH

“I wanted to be Batman”

In October 2017, Josh had suicidal thoughts and called his brother. Some weeks before, he had checked his “parent mindset asking them if it was a sin to be a trans person”. “Because my mother is very religious and my family is very conservative,” he explains.

In Uganda, “we are subject to blackmail, to media outing and all forms of violence”

In Uganda, loving can be very dangerous. The country is labelled as one of the worst places to be LGBT in the world. In 2011, David Kato, a teacher and the father of Ugandan LGBT activism, was killed at his home in Kampala after helping to send to the court a local newspaper that had published at front-page the name, pictures and address of 100 gay people together with the banner: “Hang Them.”

As in other states across the world, colonialism left a print difficult to erase. The territory of today’s Uganda, that once was not a country but a series of different kingdoms and communities, became a British protectorate in 1894. Thus, as in most of the Commonwealth, the laws on ‘unnatural offences’ were introduced. The Uganda Penal Code criminalised same-sex sexual relations under the section 145, 146 and 148 in 1950 based on the section 377 of the Indian Penal Code of 1860. After independence, the law, and homophobia and stigma survived.

In 2014, Ugandan legislators passed a bill that attempted to introduce the death penalty for LGBT people but soon was annulled thanks to the work of some organisations. However, mobs and lynching followed it.

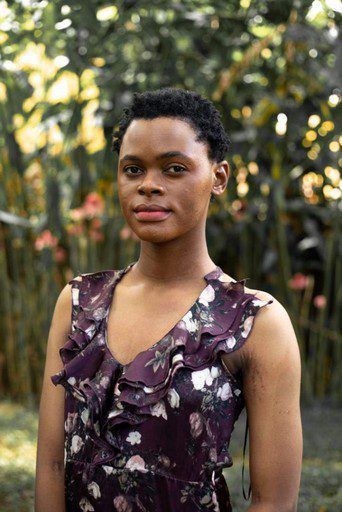

Ugandan Photographer Kwagala DeLovie has captured the feelings and dreams of four Ugandans amidst the Section 145.

GLORIA

“It is very disappointing seeing how much of the colonial imprint still exists, and it does not make any sense to keep it,” says Gloria.

SEVERUS

SEVERUS

Severus explains that the section 145 of the Ugandan Penal Code Act is quite similar to the 377 section of the Indian Penal Code on “unnatural offences” that was introduced by the British in 1860 and has been used for over a century to normalize several injustices against LGBTI people and the hostile rhetoric around them.

GERALD

GERALD

“I learned early that there was a particularity about me and how people reacted to me, either aggressively or violently,” Gerald says, who explains that learning about the history in Uganda under sections 145 , 146 and 148 of the Penal Code and learning about the colonialism behind it and learning the history about the tribe Gerald belongs, was able to see their place here.” “That I am legitimate and these laws are dangerous and destroying lives.”

AMANDA

AMANDA

As a transgender person in Uganda, Amanda explains that they are “subject to blackmail, media outing and all forms of violence.” In 2017, her family found her sexual identity as a transgender person, and she was sent to a prison facility and submitted to police brutality - since then, she is afraid.