The walls

of Europe

The European Union, whose policy was welcoming of migrants during the refugee crisis in 2015, currently finds itself enclosed and traversed by over 2,000 kilometres of border fences.

Victims

In a deliberate and almost methodical manner, a burly man points out the damage inflicted on the facade of his home by fragmentation grenades. "They launched three. Luckily, only two detonated," he recounts on the doorstep of his residence on the outskirts of Hajdukovo, a Serbian village located at the border with Hungary. The barbed wire crowning the double fence that separates the two countries looms in the distance.

The neighbour speaks in Hungarian, like most of the population in this Serbian region, and he refrains from disclosing his name out of fear of reprisals. He asserts that the grenades were hurled in front of his home by human traffickers after he had repeatedly reported them to the police. He fears that next time they may be thrown inside while his family is sleeping. For now, his residence has been the sole target, but the sound of gunshots has become a routine occurrence for the people living near the border.

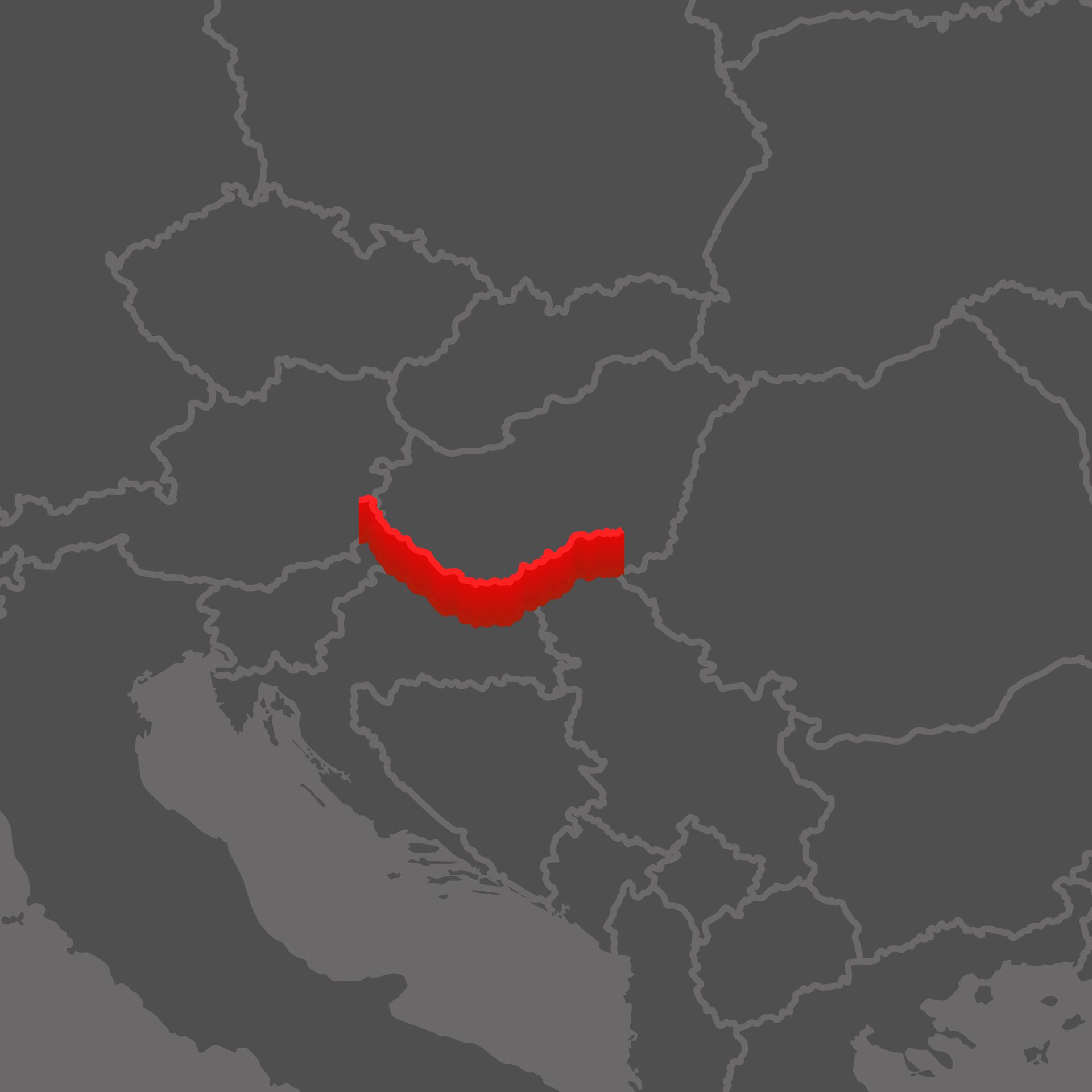

Eight years after Hungary's decision to construct a fence aimed at preventing the entry of refugees and migrants passing through the territory of its southern neighbour, the situation along the Serbia-Hungary border has reached a critical juncture. The challenges associated with crossing the border, coupled with the legal framework implemented by the government of Viktor Orban, which sanctions and mandates pushbacks, have forced migrants and asylum seekers into a state of complete reliance on human traffickers, whose influence and violence has grown significantly in recent years.

Human trafficking networks have always been part of the so-called Balkan Route, but the strengthening they have experienced over the past year is unprecedented. These criminal organisations control most of the territory in the last few kilometres of Serbian land facing the Hungarian border and have recently begun fighting each other for control, using firearms provided by the Albanian mafia.

The gunshots are also heard on a dialy basis on the other side of the border, in the Hungarian village of Ásotthalom, where many people, despite recently electing a far-right candidate as their mayor, are starting to believe that the border fence might have been a waste of money. "It starts in the evening, around 8PM. Between three and four hundred every night,” says Gÿongyi Bodo, a local neighbour. “They just try to flee, but the smugglers come first and threaten us.”

Migrants and asylum seekers are increasingly vulnerable to mistreatment, kidnapping, and rape if they do not pay the amount requested by human traffickers or if they are caught trying to cross on their own. Ahmed, a young Syrian interviewed in the Subotica refugee camp, a few kilometres away from Hajdukovo, describes that the violence has even reached the facilities themselves, which are supposed to be controlled by the government. He also describes how his brother was recently kidnapped near the border for days and forced to pay hundreds of euros for his release. "The police or the border guards don't scare me anymore. The smugglers do," he says.

Even in cases where migrants successfully cross into Hungary, they frequently encounter violence at the hands of security forces. Organisations like the Helsinki Committee have been documenting these abuses for years, which notably include mistreatment of unaccompanied children.

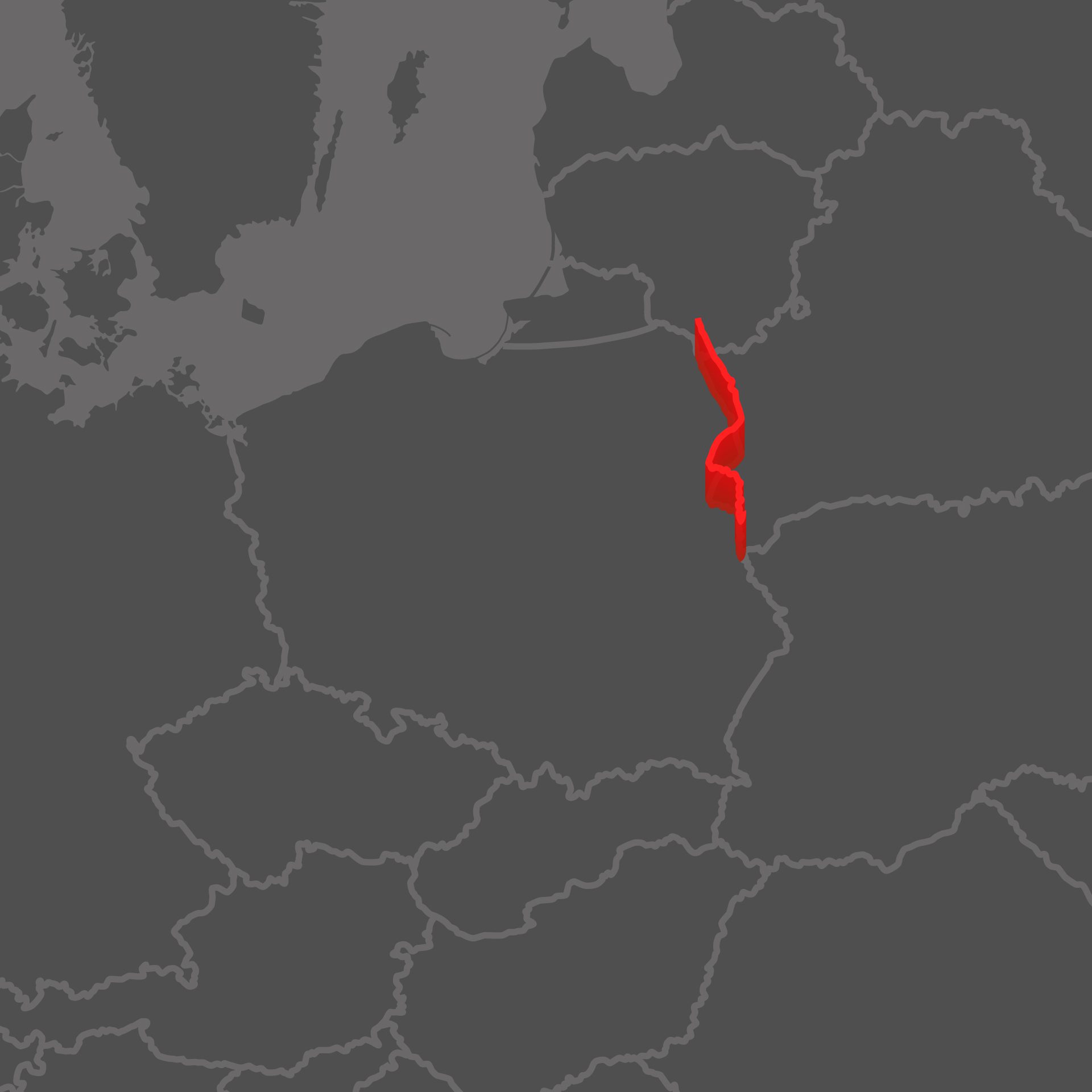

In the summer of 2021, an unprecedented migration crisis broke out on the border of Belarus with the European Union countries. A crisis like this that had never occurred before on such a scale in this region. The number of attempts to illegally/irregularly cross the borders of Belarus with Poland, Lithuania and Latvia by migrants mainly from African and Middle Eastern countries -such as Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan- has grown rapidly. According to official data from the Polish Border Guard, almost 40,000 crossing attempts were registered in 2021 for the Belarusian-Polish border.

Belarus was accused of causing the migration crisis by issuing tourist visas to migrants and offering transport to Europe for a fee between PLN5,000 and PLN10,000. Belarusian ruler Alexander Lukashenko admitted that supporting illegal cross-border migrant traffic is a response to European Union sanctions against Belarus. For Russia, fierce supporter of Belarus, migrants are an instrument to cause pressure, provoking a direct threat to the security of neighbouring countries, which threatens the stability of the EU.

This situation was, however, new for everyone: those in power, residents of border areas, activists, aid organisations, doctors and businesses.

Consequently, the governments of Poland and Latvia first decided to introduce states of emergency in the border areas with Belarus, while the government of Lithuania declared a state of emergency throughout the whole country. In Poland, from September 2 2021 to July 1 2022, a ban on staying in the border zone took place in 183 towns in the Podlaskie and Lublin voivodeships, adjacent to the border with Belarus.

The following decision was to build a barrier on the border: on November 4, 2021, Polish President Andrzej Duda signed the act to build the “state border security”. The aim was to stop illegal/irregular crossings through the state border. The first construction works began in January 2022 and, on June 30 of the same year, the Border Guard announced the completion of the works. The cost of the project amounted to 1,6 billion PLN. The contractors of the investment were Budimex and the consortium of Unibep and its subsidiary Budrex.

“When it turned out that not only our Polish government was building a wall on the border and was against migrants, but also that the whole of Europe was like that, it was a shock for me. I thought we would complain and the European Commission as well as the European Union would support us; the world would support us. But it turned out that we were doing the same thing as the EU, and that the EU would support what Poland was doing," says Joanna Łapińska, a resident of Białowieża.

The dam is 5.5 metres high, with 5 metres of steel poles topped with a half-meter-long wire coil. Over 50,000 tons of steel were used during its construction.

Breaking through such a barrier is difficult. For the hospital in Hajnówka, the construction of a barrier on the border did not reduce the number of hospitalised people, but unquestionably worsened their condition. Because of the border wall, the patient profile has changed: in 2021, people were admitted exhausted, malnourished and hypothermic, leaving the hospital after several hours or at most a few days.

“Since the construction of the wall, the number of injuries has increased significantly and, what's worse, the injuries here are very serious. These are multi-site injuries, fractures of two limbs at once, fractures of one limb in several places, and spine fractures also occur. These hospitalisations often last a long time, and we have no place to accommodate these patients," says Dr. Tomasz Musiuk, an anaesthesiologist from the Hospital in Hajnówka.

The wall was to include 100 service gates and 22 animal gates, however, the animal gates remain closed, which has affected the migration of wildlife, especially the lynx, an endangered species in this area. “Dams, walls and border fences are one of the greatest threats to wildlife. They prevent animals from moving and migrating. There is no gene flow, so they cause isolation," says Prof. Rafał Kowalczyk from the Institute of Mammal Biology of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

The border barrier has not been successful at stopping human migration, but it has segregated most other species that previously lived in the area.

Once a land of emigrants, Spain became a transit and destination country for migrant flows when it joined the European Union. One of the first reactions of the Spanish government was to build up a wall in Ceuta and Melilla –the only two European cities in Africa–.

These fences have a direct impact on the lives of many people, from those who migrate to those who guard them and the locals.

Melilla's 12-kilometer-long border perimeter is currently surrounded by five border fences equipped with state-of-the-art technology and a three-meter-deep moat. The wall is designed to discourage and prevent any sort of jumping over it, but the crossings continue unabated.

This reality became clear on the morning of June 24, 2022. Sources from the Guardia Civil, the Spanish intelligence service and several survivors say that Moroccan forces encouraged a mass jump attempt involving around 2,000 people, mostly refugees from Sudan. That was the deadliest day on a European land border: at least 37 people died, according to Amnesty International. Seventy-six are still missing.

Sulaiman Abu Bakr, a 24-year-old Sudanese, survived the massacre. This young man is one of the 130 refugees who managed to jump the fence. After 10 years of migratory route through the Sahara and 14 attempts to reach Spain through Ceuta, he finally succeeded in Melilla. Sulaiman has still gotten not over the trauma. He remembers how he was trapped in the tangle of steel and wire, between the stones and tear gas bombs of the Moroccan police and the pepper spray of the Guardia Civil agents. His inert body was trapped in the mountain of people that formed on the line separating Spain and Morocco, as shown the videos from that day. His next memory is the hospital bed. “I think a lot about the ones who didn’t make it.”

Sulaiman now lives in Seville, where he awaits a response to his asylum application. A social worker at the migrant detention centre in Melilla who nursed him and other people that day highlights the serious injuries caused by the fence: deep cuts, trauma to limbs and head, irreparable loss of mobility and vision.... "The fence only serves to make people more vulnerable," the social worker explained.

"I do not think building walls will stop migrations because migration has always existed in this world. Nothing will stop migrants except death," says Houssain Mohamed, a 23 year-old Sudanese who was granted asylum in Spain after jumping the fence in March 2022. "I think the money spent to build the walls could be used to support countries in conflict and to solve problems from the root,” he adds.

One of the voices that are usually forgotten is that of the Guardia Civil agents deployed at the border fence. "In Melilla they can't keep us for long," explains under anonymity an agent who participated in the June 24 operation. "The worst moment is the one after [the border action], when you are left alone. You go from shrieking to silence. You take off your uniform and you see the blood." He highlights the high suicide rate among officers posted at the border fence. "I didn't join the Guardia Civil for this," he says.

Migratory flows are like the course of a river: walls do not stop the flow of water but rather alter its course. The line between Melilla and Morocco marks one of the highest economic inequality gaps in the world. Poverty, corruption and violence drive many Moroccans to try to enter Melilla.

"Life before the fence was totally different," says Maite Echarte, a Melilla native and human rights activist who devotes her time to supporting children who migrate alone. "Now the city is like an open-air prison," she says. Echarte recalls that, in the past, Melilla lived in harmony with the neighbouring Moroccan populations. Young people from both sides played soccer together while adults visited family and friends. Goods, culture, knowledge and also love flowed. The border fence put an end to all that.

Noora Saber, a 32-year-old Moroccan woman, arrived in Melilla when she was 10 years old in order to be raised by her aunt and uncle, a Civil Guard agent. "I wish they would open the fence," she says as she expresses anguish because her two children, born in Spain, still do not know their grandparents. The infants do not have Spanish documents and if they go to Morocco they will not be able to return to Melilla, their home.

The photo of a group of migrants perched on the fence of Melilla in front of a golf court built with European funds went viral worldwide. The city’s beaches, its modernist architecture and its gastronomy are in the background.

Many Melillans are wary of journalists because they convey a negative image of the city. However, they also suffer from the border fence. A paradigmatic case is that of Miguel Ángel Hernández, a retiree from Melilla whose house was left isolated on the Moroccan side after the construction of the fence. This Melilla native complains that, since the pandemic, Morocco prohibits the passage of goods and keeps the customs office closed. As a result, Miguel Ángel cannot even bring new towels or sheets to his home.

Days before leaving office, Melilla's president, Eduardo de Castro, pointed out that the border fence turns the city into a de facto island. He highlighted a contradiction: the fence was created to prevent migrants from arriving, but its effect on the economy, tourism and the lives of Melilla residents is harmful. The fence is a double-edged sword. "Morocco uses the fence to put pressure on Spain and the European Union to gain advantages and money," he said.

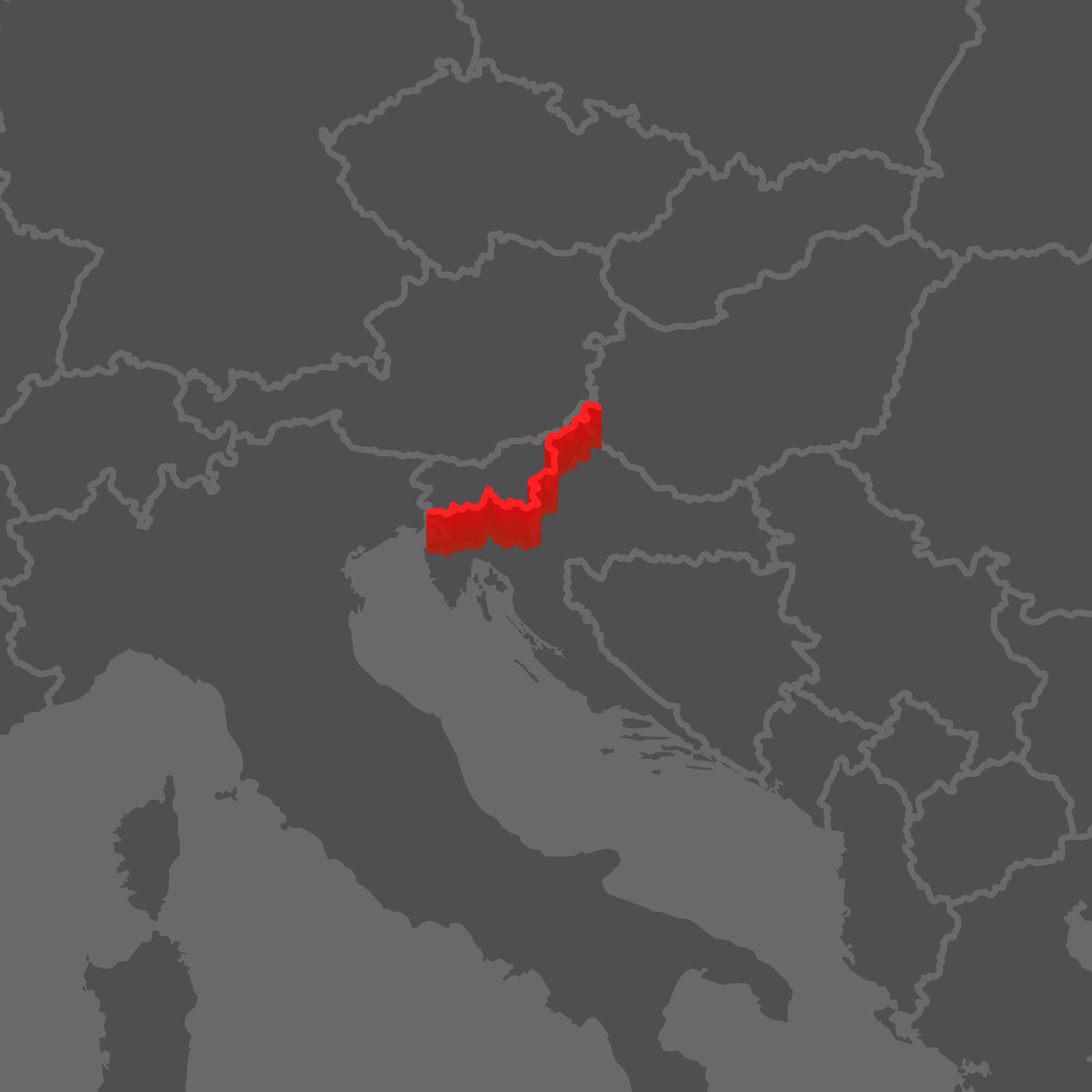

After stowing away on a ship to Montenegro, walking in the rain and cold through the Bosnian forests, surviving the winter in an abandoned house WHERE and traversing Croatia, when he finally crossed the Kolpa River, a natural border between Croatia and Slovenia, Desmond* ran into the human barrier: a fence patrolled by militarised policemen.

It was the second time he entered Slovenia. The first time, he had been fingerprinted at the police station and "put in a van with other guys,” this 28-year-old Cameroonian, father of a six-year-old girl, recalls while fiddling with the beads of his wooden bracelet in a cafeteria in Ljubljana. “I then discovered that I was on the border with Croatia again, where the police stripped us naked, leaving us only in our underwear.” “In Croatia they said that it was just a couple of bad apples. That is, isolated cases,” explains Josh Zagar, a member of the civil initiative Infokolpa. Between 2018 and August 2021, the Slovenian police carried out 28,235 pushbacks to Croatia, according to the initiative.

At the end of 2015, in response to the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ in Europe, when nearly a million people, mostly Syrians and Afghans, fled their countries and tried to seek refuge on the European continent, Hungary closed its border with Croatia and thousands of refugees diverted to Slovenia, the first country in the Schengen zone (after Hungary) of the commonly known as Balkan route.

“I remember the day Hungary closed the border. The last trains were full of children and women; there was a pregnant woman with six children,” recalls Ognjen Radivojevic, head of the Integration and Guidance Program at Filantropija organisation. “I like the people here, but the immigration policy is not right, I have waited four years to get a refugee status,” said Kristina, a refugee from Ukraine, who is fluent in Slovenian.

When Hungary closed its border in 2015, Slovenia's response was to build a 194-km-long fence on the southern border with Croatia. “The fence is symbolic. I think it is for us [Slovenes], they are sending us a message: something dangerous is coming and we have to protect ourselves,” said anthropologist Zana Fabjan Blažič, co-founder of Ambasada Rog organisation.

Almost seven years after the 2015 crisis, in May 2022, when the current Slovenian Prime Minister, Robert Golob, took office, Slovenia announced that it would remove the fence.

In August 2023, a team of reporters from this investigation accompanied the Kočevje police to the area where the fence was dismantled. As a visual metaphor, the Čedanj Bridge, built decades ago to connect the Slovenian and Croatian shores, is now covered with barbed wire. “The fence is forcing people to cross in hostile environments, with cliffs, deep or speed water,” said researcher Marijana Hameršak.

Between 2015 and July 2023, at least 97 people died in Croatia and 27 in Slovenia while trying to migrate, according to the Zagreb Institute for Ethnological and Folklore Research. "Building this fence was the stupidest thing they could do here," Branko yells under the bridge that connects his municipality, Zamost, in Croatia, with Sela, Slovenia. His house is just on the border. “We used to cross in both directions [freely] and marry each other.” At the Muhvic campsite, bordered by the fence, a user complains: "It looks ugly." “It used to be a very vibrant place, we want bikes and communication back,” agrees Joze, 78, a neighbour.

The fence had also unforeseen consequences on wildlife. In a room adorned with antlers and tusks, Mladen Koritnik, president of the Banja Loka Hunters Organisation, explained that when the wire fence was installed, deers got stuck in it; then, in 2017, the government ordered to replace some razor-wire for panels, and the foxes started to use the panels to capture deers. “Some animals also drowned in the river,” he adds. At least 56 animals died on the fence between Slovenia and Croatia between 2015 and 2023, according to the Slovenian Hunting Association.

“But the biggest impact of fences will be in the long term,” said Dr. John D. C. Linnell, Senior Scientist at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, “we are going to see genetic problems.” “Western Europe is becoming ecologically very isolated from the East,” Linnell concluded.

The fence is just the beginning, followed by years of obstacles. While waiting for his refugee status, Rachid, an Iraqi man who worked as a hairdresser in his country, cooks kebabs in a restaurant in Ljubljana and cuts the hair of homeless people for free. He believes that he will never see his wife and children again. He said goodbye to them when they fled to Turkey. He cannot return to Iraq, where he fears reprisals. “I have lost everything,” he laments.

It was a night of August, at 5am, in the city of Burgas -primarily known as a tourist spot, especially for people from former communist countries- when a bus with migrants hit a police car and killed two Bulgarian policemen. This event marked a turning point for the government on how to handle migration. It was used to allow even more brutality from police and border guards, aimed at those who are trying to cross the border wall and enter the European Union through the Bulgarian border. On December 5 2022, a video proving that a 19-year-old refugee Abdullah El Rustum was shot on October 3 surfaced on the internet/web/online.

Burgas is 120 kilometres from the border, a little over an hour drive. The whole Bulgarian - Turkish border is 513 kilometres long and cuts through the Strandza National Park, where most of the refugee crossing attempts take place. Although walking through the terrain is not easy, it offers the cover of the tight forest and hills. Employees of the national park are sure the wall has affected the routes and life of local wildlife but they do not collect any data nor are willing to speak under their names. When asked why, they say it would not be politically advised: the National Park is a public institution and as such can be influenced by politicians.

Going south to a different part of the border, a couple kilometres from the official border crossing between Bulgaria and Turkey, lays the city of Svilengrad – crawled with casinos, since gambling is illegal in Turkey. Going up to the mountains along the border. The road soon becomes almost impossible to drive on. A distance of 30 kilometres turns into a two hour-long trip due to the amount of potholes.

The last accessible village is Matoczina – just a few metres away from the border wall. Only the elderly remain in the area as all young people leave whenever they can afford to. “Have you seen the road here? We have been waiting for years to get a new one, but the wall was built instantly. Explain this to me,” an old lady complains as she laughs ironically.

On this part of the wall the number of crossings is much smaller as the area does not offer as much natural cover as the forest in Strandza. Bulgaria announced the construction of a 30-kilometre-long barrier between Lesovo and Golyam Dervents in January 2014, and a 130-kilometre extension and reinforcement in 2015. On some parts of the border next to the new wall the old fence dating back to communist times can still be seen. Back then it was supposed to prevent people from fleeing Bulgaria. Now times have changed and new issues have arised, so a different barrier is required to stop the migration flow. Only in 2022 there were 155,000 crossing attempts, according to the Bulgarian border guard.

Those migrants who made it and are not push-back are taken into different detention centres. One of them is located in Lubimec. Here migrants wait for the procedure without the possibility of leaving the facility. One of the most extensive camps, where migrants who are granted permission, stay, is in the city of Harmanli: A 18,000 people community with a refugee centre where almost 2000 people live. Migrants can move around freely and try to find a job, but the situation is extremely challenging. Bulgaria is one of the poorest EU countries and has many internal struggles - especially related to corruption and political instability. The local community cannot understand why their small town must be a host to such a proportionally big group of migrants. They would like for them to be transferred to a larger number of cities in smaller groups. “But the local administration is very passive,” says Daniel Grozev, from Harmanli. “There is nothing the government does besides putting them in the centre.”

Hamid Khoshsiar, who made it through the wall, was picked up by the Bulgarian border guard, and now works at the community centre. While sitting in one of the few restaurants in the center he talks freely. He provides his help to lift up the spirit of the community, help them find jobs, provide medical care and translate when needed, but admits it is extremely tough to integrate.

Various incidents also occurred - an Afghan boy drowned in the Harmanli river in the summer of 2023. Hamid, together with Diana Dimova, work at an NGO “Mission Wings Foundation” that supports migrants in Bulgaria. They receive news of the brutality of pushbacks at the border daily. In July, a van with 58 Afghans was found close to the border with Turkey. Twenty-three of them were unconscious. Many refugees die in the Strandza forest as they lose track, starve due to the lack of food or are separated when trying to escape the services being guided by smugglers.

“You don’t cross the wall, you buy the road,” concludes Hamid, adding that the main consequences of the existence of the wall are an increased number of injuries and deaths of refugees, however, this does not stop them from attempting to cross.

Hiding in a small forest near an industrial estate on the outskirts of Calais, a dozen people from Sudan hang wet clothes on tree branches. These young men, most of them war refugees, know that the Police will soon arrive and, without a word, beat them before forcing them to run away to a new hiding place. Every 48 hours, the French gendarmerie sweeps the area in search of hidden migrants who intend to go to the UK to seek asylum, in order to work in a country whose language they master, or to simply be reunited with their surviving family members. Some of the interviewees whose testimonies are included here have been wandering the few remaining forests in the area for more than three years.

Calais is a hotspot for migratory routes. It is the closest French city to the United Kingdom, barely 30 kilometres away, and is the mandatory passage for goods and citizens who wish to cross the English Channel by ferry or train through the Eurotunnel. Until 2016, the town was surrounded by forests where more than 10,000 migrants used to survive in an informal camp, known as the Calais Jungle, waiting for a chance to cross into the UK. That year, French authorities destroyed the camp and accelerated the construction of walls and the clearing of forests.

Since then, migrants have been looking for alternative routes and the number of those who are taking to the sea in plastic boats is rapidly increasing. At least 2,384 migrants have lost their lives so far this year, according to the International Organization for Migration.

"Since I arrived in Calais, I have lost three friends," says Waliadin Mohammed, a 27-year-old Sudanese, as he prepares coffee with ginger, while hiding in the woods. Going unnoticed is not easy: "There are cameras everywhere," explains Hamid Younis, an also Sudanese 19-year-old. Both are afraid and visibly tired and malnourished. The two of them applied for asylum in France, without success. Now their goal is to reach the United Kingdom.

These young people do not know how to swim but their only alternative is the sea. The construction of fences and the reinforcement of the migratory control have resulted in the local mafias increasing their supply for rubber dinghies. "The intermediaries now ask for fees between 1,000 and 1,200 euros," Mohammed assures. People from countries that are assumed to be more wealthy by the mafias pay up to 8,000 euros to cross, according to the French Police. The regional and Police authorities in Calais declined to comment on this report.

On the horizon, metal fences and barbed wire are glimpsed where once only sea and dunes were visible. This city and its port now look like an open-air cage, surrounded by restricted passage zones and more than 60 kilometres of securitised fences equipped with cameras and the latest people-detection technology. Some sidewalks are occupied by large stones placed to prevent migrants from camping or sheltering from rain.

In an industrial estate on the outskirts of Calais, inside a warehouse that stores blankets, food and other basic necessities, dozens of activists work day and night. Among them is Aurore Vigouroux, project manager for Calais Appeal and Channel Info Project. This young woman explains that the establishment of fences is a key point of the French authorities' "zero settlement" policy. "The violence here is very visible: these people have no water, no light, no dignity," she says referring to the migrants.

The inhabitants of Calais are tired of the Police-State-like atmosphere. People who voluntarily help the migrants, who often include women and children, denounce that the French state criminalises and persecutes them. These people also express strong discontent with the present feeling of insecurity and the bad image of their small town in the international media.

Walls are not the only factor that separates locals from migrants in Calais. In order to guarantee that settling anywhere becomes an insurmountable challenge, local authorities are accelerating deforestation and withholding essential resources such as water supply and waste management from migrants. This not only exacerbates environmental degradation but also generates waste, sparking tensions with neighboring communities. Chloé Magnam, born in Calais, explains that "the lack of communication creates prejudices, some people blame migrants and think they are dirty." Magnma is an activist with the environmental organisation Calais Ploubelle (a word game using 'poubelle', garbage, and 'belle', beautiful), which fights against the environmental impact of anti-migrant walls. "In such a divided context, hostility grows and dialogue is more difficult," says Fanny Laborde, from Calais Ploubelle.

“I will not take any step backwards”, said Greek prime minister, Kiriakos Mitsotakis, in January 2023 regarding border protection and the security of citizens living in the adjoining area with Turkey.

Greek politicians usually visit Evros, the land border area with Turkey, twice a year. Their visits are described as “symbolic” and they are keen in using a different word for the citizens living here: “akrites”, a term from the Byzantine Empire that describes the frontier soldiers who used to guard the eastern border with Muslim nations.

However, as Greece invests hundreds of millions of EU and national funds for the border’s management, and each year more police SUVs and military vehicles are seen along the militarised region, factories are out of work, villages are deserted, and vast areas of land remain uncultivated. Locals feel abandoned by the state: for most young people, joining the Border Guard is one of the few professional options available if they wish to stay in the area.

In September 2023, this abandonment was felt stronger. The largest fire ever recorded in the history of the EU sparked from this area, burning for more than two weeks and devastating the Dadia Forest National Park. Nature was not the only victim: the fire killed at least 18 migrants. According to a report by the New York Times, most of them had already been pushed back to Turkey from Greece; when they saw the fire, they had to choose between informing the authorities —risking another pushback— or remain hiding in the forest.

The panorama captured by a drone in Mavrovouni on the island of Lesvos in August 2023 shows the impact of the migration control industry, which is not only human but also environmental. In this case, it is not one wall, but several walls that border the new Closed Controlled Access Center of Lesvos, built after the destruction of the Reception and Identification Center in Moria from a fire in September 2020. Local ecologists warned that this new structure, designed for 3,000 people in the heart of the largest pine forest in the Aegean in Greece, could cause serious damage to thousands of hectares of virgin forest if a fire started.

Pushbacks, recorded since the 90’s, experience an unprecedented operational scale. This investigation found out/unveiled that victims, some of them unaccompanied minors, are not only apprehended at the border area. Buses travelling to other regions are stopped, while people perceived as migrants —including at least one Frontex interpreter— are being abducted in cities as far as 400 km from the border and then find themselves/are found on the Turkish side shortly after (añade esto si eliges la segunda opción). “We are afraid to go out to the city after work,” said a third-country national who works for an NGO in Orestiada, less than 20 km from the border.

Since the incidents with Turkey in March 2020, Frontex has increased its manpower in Evros. The Agency’s personnel appear to be operationally supporting the pushbacks. Mamun, a migrant from Bangladesh that hoped to meet up with his brother in Athens, was reportedly seen by the journalists in charge of this investigation with his face and arms wounded shortly after crossing into Greece. He said he had been attacked by men wearing what he described as uniforms without insignia, who didn’t speak Greek, and who also stole his money. He managed to escape while they were beating two of his friends.

An investigation by Solomon and El País has documented not just the rise of pushbacks, confirmed by many media investigations and international organisations’ reports, but also an increased interest of Greek border guards for the migrants’ money and belongings. Sources from the area commented on border guards’ children showing off their brand-new cell phones at school.

The Evros River, a natural border between Greece and Turkey, poses a significant risk for people on the move. Local coroner, Pavlos Pavlidis, estimates that more than 1,000 migrants have died on the border since 2000. The main causes of death are drowning in the river and hypothermia, but also train accidents, as people walk on the railroad at night to avoid being seen.

In collaboration with migrant communities, Pavlidis attempts to identify those who perished along the way, in order to provide their families with closure. However, he is often unable to do so, as the river claims many of the bodies.

from this?

Mora Salazar was a family company that sold fences for homes and small businesses. In 2006, Spain hired the services of Mora Salazar to install a razor wire on the border walls of Ceuta and Melilla. Now the company is a multinational corporation renamed European Security Fencing, with offices in Brussels and Berlin and business in more than 30 borders around the world. "When the Socialists get into the government, I remove them. If the conservatives are reelected, I put them back. I have already taken them down and put them up four times and each time I get three million euros", admitted the owner of this company.

The companies that make profit from the fences of Ceuta and Melilla accumulate more than 120 revolving doors, including a dozen former government ministers from the Popular Party (PP) and Socialist Party (PSOE). Spain does not disclose the total expenditure on these walls "for reasons of national security." This investigation analysed 188 public contracts for these two fences worth 133 million euros.

The largest boom in the business of border fences in Europe took place after Viktor Orbán's decision to wall off Hungary's border with Serbia in 2015, amid the 'refugee crisis'. Estimates suggest that Orbán has spent more than €2 billion to build that wall. Among the companies that benefited the most is metALCOM Zrt, whose main shareholder is Zoltán Bozó, a businessman and member of Fidesz, Orbán's party, as revealed by the media Index.hu.

Orbán's decision produced a domino effect and other European countries quickly followed suit. Calais, a small historic town in France and a destination for migrants trying to reach the UK across the English Channel, is currently surrounded by 65 kilometres of fences equipped with the latest technology, including state-of-the-art drones, night cameras, and step and CO2 detectors to locate migrants through their breath. Greece, the gateway to Europe for eastern migratory routes, has an allocated budget of 819 million euros in European funds to further strengthen its border until 2027. In total, the 27 countries that make up the EU are currently fortified with 1,800 kilometres of walls.

“The erection of fences is not an adequate solution to prevent irregular migration," said the Slovenian Minister of the Interior in a questionnaire sent by the team in charge of this investigation. The removal of the border fence between Slovenia and Croatia led to a great controversy: Slovenia granted 7 million euros for the removal of the fence to Minis, the same company that installed it in 2015. Minis "did not have a single employee one year before the successful tender, and was based at the same address as a local branch of the then-ruling party," says a representative of Transparency International Slovenia. The contract was awarded without a public tender.

European governments see people on the move as a security problem and prioritise funding for walls over socially urgent investments. "Have you seen the road here? We are waiting years for a new one, but the wall was built instantly", said an elderly woman from Bulgaria –one of the poorest countries in the EU– who lives in Matoczina, on the border with Turkey.

Border walls are double-edged weapons. The other side of the business is played by both smugglers and authoritarian governments bordering Europe. On one hand, mafias rise their fees to transport migrants in increasingly dangerous and violent conditions. On the other hand, the growingly militarised walls allow the weaponisation of migrants by governments and dictatorships ranging from Turkey to Morocco, Belarus and Tunisia. These regimes are conditioning their expanding control/influence of the other side of the border in exchange for money, diplomatic support and other concessions from the EU.

got here?

Shortly after the onset of the 2015 refugee crisis, Viktor Orban, Hungary's Prime Minister, made an unprecedented decision for a country that had, until then, never exhibited any aversion to asylum seekers. Characterising the arrival of migrants as an "invasion" and a "threat" to Europe, he announced the construction of a barrier along the entire border with Serbia. At that time, the Hungarian leader stood as a solitary voice in the halls of Brussels while the Union showed commitment to the provision of refuge to victims of the Syrian civil war. Today, we know that Orban was not destined to become an outcast but rather a pioneer.

"Nobody will admit it in this town, but yes, Orban's narrative is prevailing," confessed a senior Brussels official to Politico in 2017. Only two years had passed, but the transformation was already striking. Virtually all European leaders who had once championed the humanitarian duty of hosting refugees had abandoned their rhetoric, apprehensive of the rising popularity of those parties echoing the Hungarian leader's arguments. The concept of Fortress Europe was departing from its academic origins to firmly establish itself at the core of the continental psyche.

What was once a solitary discourse on the fringes of the EU has now become the norm. Whether in the far-right governments of Poland and Italy, the right-wing ones of Greece and Austria, the liberal administrations of France or the Netherlands, or the left-wing ones of Spain or Germany, one will be unable to find any policy contrary to the maintenance and expansion of border fences. Even within the German government, which once stood as the primary standard-bearer of refugee solidarity, the Green Party now calls for an acceleration of migrant deportations.

As Donald Trump keenly understood when he launched his now infamous 2016 presidential campaign, walls and barriers carry potent symbolism. There is no more visually compelling and direct way to sell a solution to a country’s migration challenges. Yet, decades of failed policies have demonstrated that no border wall, regardless of its scale or scope, can halt the inexorable flow of global migration dynamics.

The cases reported along the now seemingly endless walls of Fortress Europe once again underscore a reality that remains impervious to simplistic solutions: hard borders do not dissuade migration; instead, they engender hard border dynamics. They redirect migrants and refugees towards more perilous routes, escalating the incidence of fatalities, whether in the treacherous waters of the Mediterranean Sea, the dense forests near Poland and Hungary, or the narrow corridors between the border posts of Melilla.

In the upcoming years the fight over migration will continue to play out between facts and emotions. The facts are that the European Union should welcome migrants, mainly due to low demographic and economic growth. The wealth of many EU societies needs their economies to constantly open up to younger generations and fill in key positions to keep them afloat - otherwise they risk going into recession.

Demographic fluctuations have an enormous impact on the movement of people: a shrinking or growing, young or aging population affect economic growth and employment opportunities. The causes are often high unemployment, poor labour standards or the poor economic condition of a given country. People are looking for countries with better perspectives and the current standards of the EU make it one of the most attractive regions for migrants.

In 2022, almost one million (965,665) asylum applications were submitted to the EU, 52.1% more than in 2021. This is the highest number since 2016. At the height of the migration crisis in 2015-2016, the number of applicants reached 1,221,690. The number of first-time asylum seekers in the EU in 2022 was 881,220 - 64% more than in the previous year (537,355).

The main reasons for migration include security, climate change, poverty, human rights and demography. With growing instability in regions like Middle East or Central Africa, more migrants are expected to knock on the EU's doorstep. That is even before we see the true consequences of climate migration.

For now, emotions are stronger than facts: “migration is causing great division in the European Union, and it could be the dissolving force of the EU. Despite the establishment of a common external border, we have not yet been able to agree on a common migration policy,” said the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign and Security Policy Josep Borrell in September 2023 during an interview for the British daily The Guardian. According to Borell, migration is a greater threat to the EU than Brexit.

In September 2023 a scandal broke out in Poland where the Polish government was accused of giving easy access to Schengen visas in exchange for bribes in many Asian and African countries. Over 250,000 migrants are said to have arrived into the EU via this channel. That has led Germany to reintroduce border controls on its border with Poland.

In recent years, many people have been fleeing to Europe from conflict, terror and persecution in their countries. More than a quarter of the 384,245 asylum seekers who obtained protection status in the EU in 2022 came from war-torn Syria, with those from Afghanistan and Venezuela being the second and third largest groups respectively. (Changes in the number of asylum seekers).

Anti-migration movements are fuel for populism and/or far right parties in many EU countries. Politicians use people’s fear and, instead providing them with information and solutions, they capitalise on it for their political needs. Brexit was fuelled by migration. Orban’s Hungary is very strong on anti-migration, but for eight years so was the Polish Law and Justice government. Recent political turn in Slovakia also is fuelled by anti migration.

However, this matter is not only a current issue in Eastern Europe anymore: far-right parties with strong anti-migration slogans are gaining momentum in Germany, France or the Netherlands. Current Italian government also runs on the agenda of solving the “migrants problem”.

The main challenges for the EU are “social inequalities (36%), unemployment (32%), followed by migration issues (31%). “ - according to the Special Eurobarometer on the Future of Europe released by The European Parliament and Commission. At the same time “ 91% of 15–24-year-olds believe that tackling climate change can help improve their own health and well-being, while 84% of those aged 55 or over agree. Almost every second European (49%) sees climate change as the main global challenge for the future of the EU”.

Forecasts say climate change will exacerbate extreme weather events, resulting in larger amounts of people migrating in the near future. It is difficult to estimate the number of environmental migrants worldwide but various figures range between 25 million and 1 billion by 2050.

[Walls of Europe] is a cross-border visual investigation funded by IJ4EU that combines data journalism, on-site reporting, and visualization.

It is the result of seven field trips to Bulgaria, Greece, France, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and Spain, where we conducted interviews with asylum seekers, local authorities, members of humanitarian organizations, border police officers, environmentalists, and hunters. In turn, we analyzed dozens of official documents, converting the data and visual evidence into visualizations.

This investigation shows the increasing number of border walls and fences across Europe, and exposes the growing business around border walls, its political prominence and its impact on society (migrants and refugees, local communities, security forces) and the environment.

Team:

El Confidencial: Lucas Proto, Emma Esser, Ana Somavilla, Marta Ley, Laura Martín

Fundación porCausa: José Bautista, Isabella Carril

Outriders: Jakub Górnicki, Lola García-Ajforín, Anna Gornicka, Zuzanna Olejniczak, Piotr Kliks, Arkadiusz Sołdon, Ivan Tvardov

Solomon: Stavros Malichudis, Iliana Papangeli

Baynana: Okba Mohammad, Mohammed Shubat