Qanats, the Ancient Solution to Carry Water Under Iran’s Desert

Iranian farmers of the arid lands of Yazd province have been using subterranean tunnels for nearly three millennia. Will this ancient technique survive the impact of climate change?

Photography and reporting by Fatimah Hossaini Edited by Sharif Safi

KHARANAQ, Iran – Along a reddish dirt road in Kharānaq, a rural area in Iran’s Yazd region, Mohammad Reza Ghaffari, an Iranian farmer, hoes a carrot crop. Yazd region, one of the 31 provinces of Iran, is located in the centre of the country – at an oasis between two deserts.

Vegetable crops have been possible in this area thanks to an ingenious system of underground channels that have allowed water to be transported under the desert in Iran for 3,000 years. It is the technique of the qanats.

As in other arid lands of West Asia, most of the rainwater evaporates in Iran, so the ancients discovered a way to collect it and transport it without losing it – underground.

A Qanat, also called ‘Kariz’ in Iran, is an ancient system of transporting water from the depths of the earth to the surface – used to direct and manage water for agriculture and other livelihood purposes.

These aqueducts are dug deep into the earth to connect the smaller wells that originate from the mother well. Mother wells are usually underground water springs.

However, climate change and unplanning construction of modern wells are also taking their toll on this dry area where water scarcity is a severe problem, and even some qanats are drying up.

The farmer Reza Ghaffari says that the amount of carrot harvest in the last two years has drastically decreased. “In previous years, we would also harvest cotton and wheat, but now most parts of the land have turned into deserts,” he adds. Climate change has depleted the water of the Kharanagh qanat.

Hossain Ahmadi, an activist from Kharanagh who has written a book of Kharanagh stories, explains the consequences: “Evaporation rate in Iran has been several times higher than the amount of rainfall for a long time now, and this is one of the prominent features of arid and semi-arid regions.”

Since all surface water evaporates, keeping water underground is the best way to protect it for future use. “The decrease in levels of water of qanats has reduced our products significantly”, Hossain adds.

“The Persian Qanat system is an exceptional testimony to the tradition of providing water to arid regions to support settlements,” explains UNESCO, which in 2016 inscribed eleven qanats in Iran on the World Heritage List. It is arguably one of the main pillars of cultivation in arid areas of the country.

There are more than 36,000 qanats in Iran. Some are ingenious architectural gems like the recently-restored Qanat of Zarch, which is considered the world’s longest subterranean aqueduct as it stretches some 80 km across the Yazd province. Some shafts of the Zarch qanat are in the Yazd Grand Mosque, which goes back to even before the emergence of Islam in history.

The salinity of this branch basically comes from the mere fact that the mother-well is located in a saline region and throughout history it has had lower quality compared to other branches. Unfortunately, the freshwater branch of this qanat is dried up but. The saline branch, however affected by drought, is still assisting in irrigation of the farmlands.

This invention of transporting groundwater to the surface has been one of the main water supply sources to the farmlands of more than 60,000 villages in Iran. However, with the advent of new technology, deep wells replaced qanats. The construction of those wells without proper planning caused almost 90% of the qanats to dry up, so that it is not even possible to rehabilitate them back.

Ahmad Jalili, another farmer around Yazd says, “qanats with less than twenty meters depth are greatly impacted by drought. My farmlands are irrigated by those qanats, which are more than ninety meters deep – they are less impacted by drought because of their further depth. However, lack of rain has caused a lot of problems for us, for example, I can no longer grow cotton because that requires more water.”

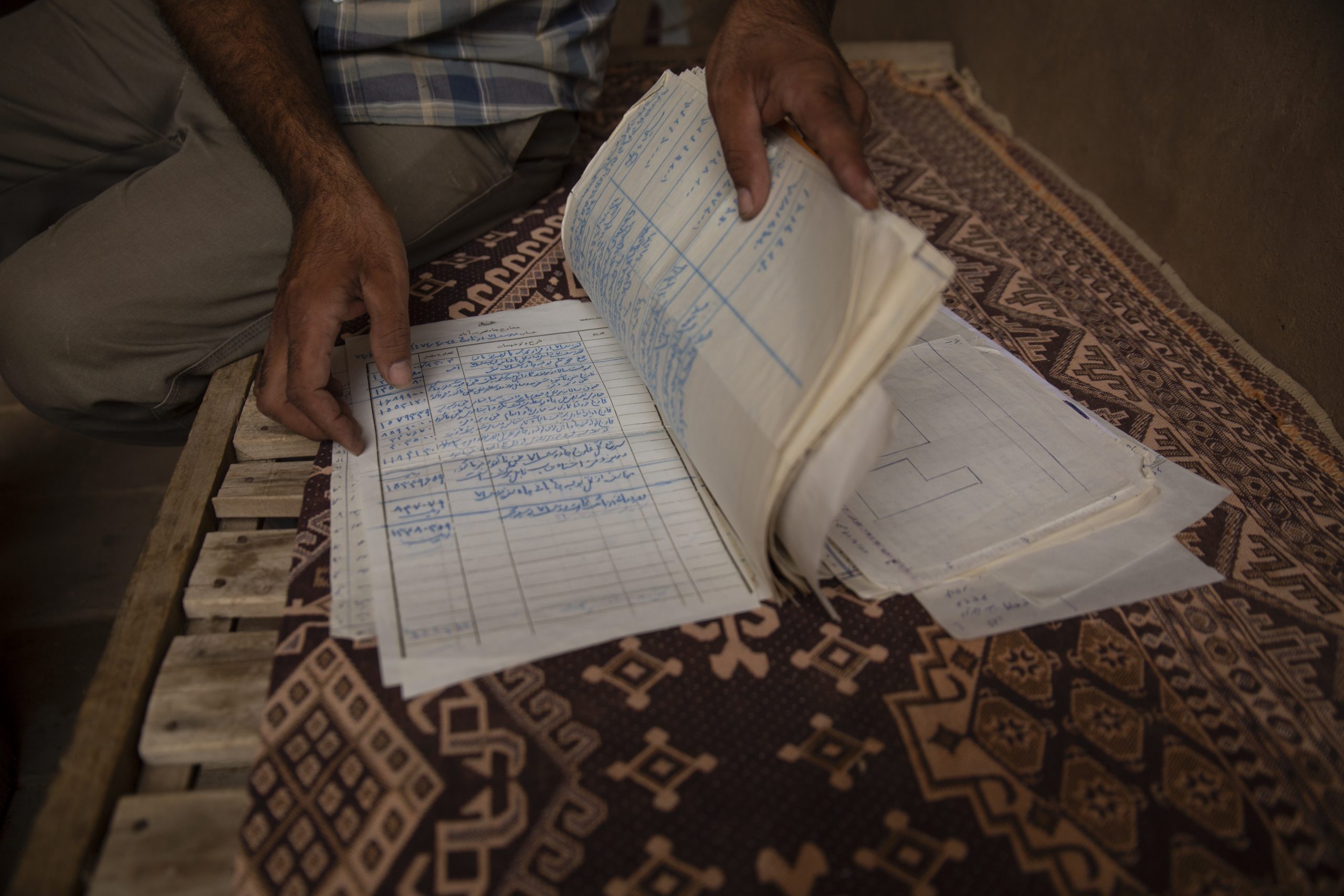

The date of birth and death of each qanat is recorded. One of those qanats which belongs to Mr Qanei’s family is now turned into a museum.

One has to go through several deserts to reach it – one of the youngest qanats of Ardakan in the middle of the desert.

However, Mr Qanei is very critical of the authorities’ inattention to the value of qanats. He believes that qanats have been damaged or/and dried not only because of climate change but also because of the negligence of the authorities, which have caused the death of hundreds of qanats.

Many qanats in the northern and southern Khorasan, a historical eastern region whose name means “land of the sun”, are also dried up as an impact of drought and climate change.

One of the guards of a qanat in the Sanandaj area says that if the government doesn’t pay enough attention to qanats, it won’t take long that those remaining qanats will dry up. He adds that many of the qanats in southern Khorasan need restoration.

Considering the arid climate of most parts of Iran but especially the southern parts, qanats have played a significant role in irrigation, agriculture, and providing drinkable water to the region’s people. However, the death of qanats shows how much excavation of deep and semi-deep wells, both authorized and/or unauthorized, have cut the lives of qanats short. Some of these unique engineering structures built thousands of years ago are being gradually destroyed. Misuse of qanats by some farmers has also exacerbated the situation.