The

Twin

Quakes

The stories behind the seismic activity that shook Turkey and Syria

in February 2023

Quakes

in February 2023

Over 50,000 people have been killed and thousands of buildings have collapsed in the deadliest quakes in Turkey and Syria ever recorded.

We met earthquake survivors in several Turkish and Syrian cities. For some of these people it is the second or third time they have to rebuild their lives.

Turkey / AdanaAdana

Adana was among the least impacted provinces near the Feb. 6 earthquake epicentre, but it did lose hundreds of residents with the collapse of several high-rise apartment buildings.

When Outriders visited the sites of those wrecked apartments on Feb. 18, nearly all the rubble had been cleared by clean-up crews working at rapid speed, likely to make way for new residential developments.

At a nearby camp, about two dozen tents were erected by the nation’s emergency response agency, AFAD, and children cheerfully ran around a playground surrounded by the temporary encampments.

Ikmet Sokal, the father of several girls, who was not displaced but said the quakes damaged the bakery where he worked, said the residents of Adana were doing what they could to help harder-hit areas like Hatay and Gaziantep.

Noting many displaced people were moving to places like Adana and the neighbouring Mersin province, Sokal said one problem facing Adana was the lack of available apartments for rent.

“Since few houses are up for rent, the government places some people in tents. It’s going to be a difficult year,” Sokal said. “I hope we’ll get through this. God willing, Turkey will get through this.”

The rental dilemma was particularly felt by Gokcar Gungorur and his wife, who requested to remain unnamed. The couple shared a tent in the park and said they had one shower in the first 13 days after the earthquakes, adding that life was becoming unbearable without basic necessities and sanitation.

“We are now looking for a new home,” Gungorur said, “But the rent prices are high. I am a person who earns minimum wage (or about 8,500 Turkish liras/425 euros a month.).”

He continued, “The minimum rent prices around here are 8,000 a month … There is no possibility for us to stay in those houses. After paying rent, I would be left with 500 liras.”

Further aggravating the already stressful period, Gungorur said safety inspectors recently certified his home as undamaged, despite the presence of visible cracks in support columns, according to Gungorur.

“They say it’s okay to live there, but there are cracks in the plaster,” Gungorur said. “We stay in the tent because of fear. We have a difficult situation. A damaged building was reported as undamaged.”

Many will continue to face similar circumstances, struggling to find affordable rent while at the same time living in subpar conditions. Yet throughout, Adana will likely become a logistics hub to serve impacted areas with humanitarian aid for the coming period.

Turkey / AdıyamanAdıyaman

After Hatay, Outriders observed the second-highest number of collapsed buildings in Adiyaman, a province northeast of the earthquake’s epicentre that witnessed some of the highest death counts resulting from the disaster.

With just 270,000 people, the central city of Adiyaman, which bears the same name, is relatively small and therefore devastated following the massive tremors.

Much of its infrastructure and buildings will need to be rebuilt, and Turkish President Erdogan promised to do that during his post-quake visit to the city, setting the ambitious goal of housing displaced residents in newly built homes within one year.

Some locals saw this as a sign of hope for better times to come and that their lives would one day return to normal, but others remained outraged by what they saw as an inadequate and slow state response in the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes.

Many Adiyaman residents said state officials and emergency response crews came too late to save their loved ones, who remained trapped under the rubble for days.

Some locals complained they paid taxes and sent their sons to military service; they also voted in favour of Erdogan’s ruling party in previous elections. But when they needed the state most, they said no one showed up for days.

Many survivors stay in tent encampments throughout the city, like Abdulrahman Demir, who lost his home to the earthquakes. Speaking from his encampment, Demir said the area lacked necessities and called for more aid towards the city.

“Electricity, food, supplies, shoes, we need everything,” Demir said.

Yet some families remained without tents when Outriders visited the city on Feb. 17. Speaking from inside a shattered storefront across the street from her collapsed home, Nurdan Altinkaynak held her 11-month-old daughter and said she had been sleeping outdoors since Feb. 6 with her baby, teenage son and husband, all without a tent in freezing winter temperatures.

“God protected my baby,” Altinkaynak said, detailing how her family was rescued from their collapsed home, but she noted sadly that her mother did not get out alive. Her husband began to cry as we talked.

After some sensitive moments, Outriders asked what the Altinkaynak family would do next. The teenage son said they were preparing to move in with relatives in Mardin, a province in southeast Turkey.

Until then, they would continue to get by on food provided by the municipality, but with slim chances to find even temporary shelter in Adiyaman.

Turkey / GaziantepGaziantep

The southern Turkish town of Gaziantep is just 32 km from the epicentre of the earthquake in Kahramanmaraş

Gaziantep’s city centre also had many encampments in city parks and squares. The main displaced population there was composed of Syrian refugees, who said their homes were no longer safe to inhabit.

This town is only about 60 km from the border with Syria.

Outriders observed municipality police distributing food and soup to Syrians in tent encampments. Still, conditions remained tough as news reports indicated refugee populations in Turkey faced more discrimination following the earthquakes. Many Syrians were blamed for looting stores amid the chaos in the earthquake aftermath.

Long-accustomed to being scapegoats for the nation’s problems, Syrians interviewed by Outriders in Gaziantep said they had received many donations and felt relatively safe, despite often discriminatory rhetoric at the national level.

Turkey / GaziantepNurdagi

While parts of its historic castle crumbled to the ground, Gaziantep’s city centre was spared the worst damage on February 6, unlike several of the province’s smaller cities, some of which were almost entirely destroyed by the earthquakes.

Not far from the fault lines, the cities of Nurdagi and Islahiye were devastated. As a result, both cities’ populations, about 41,000 in Nurdagi and 67,000 in Islahiye, were nearly all displaced. Most were staying with relatives in nearby cities or tent encampments, built quickly following the earthquakes, in the cities’ public squares and parks.

When Outriders visited Nurdagi on Feb. 13, many families lived in tents as some waited for their loved ones to be dug out of the rubble. No habitable building was visible in the city centre, with the standing apartment buildings visibly cracked or missing entire sections.

At the same time, less depressing scenes were observed as children participated in organised activities in the city’s parks. Meanwhile, adults and emergency aid workers stood in lines for hot meals served by food trucks bearing the logos of the various municipalities and restaurants that sent aid from around the country.

In the cold of winter, in areas without running water, electricity, gas or heat at the time, those warm soups and doner kebabs could be compared to lifesavers at sea for the way they could keep the mind and body afloat during hard times.

Yet challenges remained. At the encampment in central Nurdagi, Outriders observed just four portable bathrooms – two for women, two for men – for hundreds of people.

The sanitary and hygienic conditions have likely improved since the initial earthquake aftermath. Still, prolonged periods without access to basic hygienic standards can quickly lead to the spread of diseases among displaced populations, which would then worsen already difficult conditions.

Turkey / HatayIskenderun & Antakya

Hatay looks like an area ravaged by years of war, and only the damage came in one day.

There are few ways to describe places like Iskenderun on the Mediterranean coast, whose port remained in flames days after the tremors as burning chemical substances sent a plume of black smoke over the collapsed city centre.

In worse condition is Antakya, where few undamaged buildings remain on its central thoroughfare, now a scene of dust clouds and search crews working at all hours to dig into mountains of rubble. Some neighbourhoods have been completely erased as many residents remain missing.

Hatay hosts the most extensive damage and loss of life following the Feb. 6 earthquakes.

The province’s 1.69 million residents remain in shock following the instant destruction of their unique, diverse and historical cities.

Many are currently displaced, living in emergency tent shelters or have left to stay with friends and relatives elsewhere.

At the same time, some Hatay residents continue to stand by piles of rubble, waiting for their loved ones to be recovered from collapsed buildings, which killed a yet-to-be-confirmed number of victims.

The final death toll for Hatay alone is likely to be in the tens of thousands. Until all missing people are accounted for, the pain experienced by their friends and family remains too sharp for words.

Beyond the loss of life and infrastructure, the damage to Hatay cuts deep also because the province represents a meeting point for many cultures, religions and historical lines, comparable to few other areas in the Middle East.

Now the members and meeting places of those communities, the churches, synagogues and mosques are in ruins.

The citizens contemplate their next steps, knowing reconstruction will take years.

Though one of the oldest churches in Christianity, the Church of Saint Peter in Antakya, was reportedly not damaged as it is carved into the side of a mountain, Outriders could not verify its status as the site was closed to the public immediately after the earthquakes.

With the necessary resources, infrastructure and aid, Hatay residents interviewed by Outriders said they would return to their hometowns and hoped to continue their ties with one of the oldest centres of human civilization.

Over its long history, Hatay has endured many traumas, wars, plagues and disasters.

Following the initial mourning period and earthquake reconstruction efforts, locals plan to continue the area’s tradition to persevere and thrive again.

Turkey / KahramanmaraşKahramanmaraş

After Hatay and Adiyaman, Outriders observed the third-highest number of collapsed buildings in Kahramanmaras.

Many streets in the city centre are blocked by the remains of large office towers and apartment buildings that crumbled into massive piles of concrete, now slowly being removed, one scoop at a time, by armies of excavators.

Sadly, much of Kahramanmaras’ Ottoman cultural heritage is among the wreckage, including a historic covered market known as the Maras Bazaar and the 15th-century Maras Grand Mosque, whose unique, wooden-top minaret was lost to the earthquakes. (The city was historically known as Maras).

Beyond landmarks, Kahramanmaras suffered extensive damage in its residential neighbourhoods, which in the city centre are a mix of picturesque wood and mud-walled Ottoman homes and DIY dwellings known as ‘gecekondu’ or the Turkish word for slums. In these residential areas, the highest number of victims continue to be found.

When Outriders toured the city on Feb. 14, many residents of Kahramanmaras’ historic centre salvaged whatever items they could from their collapsed homes. A young man named Yasar, who withheld his last name, was spotted carrying a microwave across a fallen concrete rooftop and passing it down to his cousins.

Yasar then returned across the same slanted rooftop to reach the cracked balcony of his collapsed family home and climbed inside. A few moments later, he appeared again, this time with jars of pickles and tomato sauces, apparently emptying out the kitchen.

“We are taking anything that’s worth keeping,” Yasar said, adding his family moved in with relatives in a house that did not collapse.

Asked what he would do next, Yasar was at a loss for words, saying: “Everyone has left my hometown. They had to get shelter somewhere else.”

Ayse Kaya, another Kahramanmaras resident, echoed the sentiments and spoke to Outriders while her husband salvaged goods from his collapsed childhood home.

“Life is finished here. There is nothing left,” Kaya said.

Earthquake victims across the region often repeated her words. In their initial grief, many people interviewed by Outriders expressed doubt their lives would ever return to normal or the way they used to live before the earthquakes.

And how could they? Tens of thousands of people lost their lives after Feb. 6, and entire neighbourhoods lost their markets, streets, meeting places and traditions. Kaya recalled memories from her husband’s family home among the sad moments.

“We used to like this house so much. It was always cool in the summer,” she said.

Turkey / KilisKilis

Kilis, a small province between Gaziantep and the Syrian border, did not experience significant damage during the Feb. 6 earthquakes. Still, their aftereffects led to the temporary closure of Kilis’s border gate, an essential route for humanitarian aid flowing into Syria.

More than 4 million Syrians in the nation’s northwest rely on supplies and aid from Turkey for subsistence. Due to severe infrastructure damage in Turkey, most area residents were left without government support or humanitarian assistance during initial earthquake response efforts.

Some United Nations and World Food Programme aid convoys entered northwest Syria from a Hatay border crossing in the first week following the earthquakes. Still, the Kilis border gate did not reopen until Feb. 14.

Isolated from the rest of Syria after 12 years of civil war, several thousands of Syrians in northwest territories died during and after the earthquakes. However, many lives were spared because much of the displaced population lived in tents instead of apartment buildings at the time of the tremors.

Having experienced trauma after trauma, some Syrians inside and outside the region often express feelings that the world has forgotten them. Responding exactly to those sentiments, Luqman Vania and Abrar Khan, two humanitarian workers with One Nation UK, a non-profit organization, crossed the Kilis border gate on Feb. 16 carrying supplies with their hands.

Outriders caught up with them just before they crossed over.

“In Syria, logistically, it’s significantly harder to get aid across, and I think the Syrians are for sure feeling that,” Vania said as he carried a hydraulic lift, which works like a car jack. It lifts or supports fallen concrete slabs and is an essential tool for search-and-rescue efforts.

“We’re taking this because I was speaking to those on the other side, and they were saying we need heavy machinery, that kind of stuff, and unfortunately, we can’t take it across,” Khan said. “But this, I thought we could get it from the UK and take it across. It’s just a small gesture from us to help on the Syria side.”

This a possibly small but much-needed gesture, as infrastructure in northwest Syria was significantly damaged by earthquakes, and its population is now at high risk of food and water-borne diseases due to inadequate sanitation conditions.

Critically, northwest Syria has been experiencing a cholera outbreak since November 2022. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control warned public health conditions could worsen following the earthquakes without the necessary humanitarian supplies that flow through border gates like the one in Kilis.

Turkey / OsmaniyeOsmaniye

Ibrahim Ilhan, a teacher in Osmaniye, estimates half of the city’s 200,000 residents will move elsewhere in the aftermath of the Feb. 6 earthquakes. He plans to be in the remaining half but knows hard days are ahead for his hometown, where about one kilometre of the central avenue linking the historic centre to the train station is in disrepair.

Locals say nearly all high-rise buildings on this stretch, called Hasan Cenet Avenue, will need to be demolished and replaced with new structures. Ilhan plans to remain in the area as he stays with his wife’s family in a nearby village for the current period.

“We don’t have another place to go other than Osmaniye,” Ilhan said. “We will stay here.”

He spoke to Outriders next to his apartment on Hasan Cenet Avenue. It was located in a high-rise building that now bears visible cracks in its exterior. According to Ilhan, a worse fate hit an identical high-rise apartment next door, which collapsed in the first five seconds of the earthquake.

As a result, more than 100 people died, including many neighbours he knew. He said only five people were rescued from the building’s upper floors.

Shaking his head while looking at the rubble where so many lost their lives less than two weeks earlier, Ilhan said the school was suspended, and he wasn’t sure classes would resume considering the high death toll.

“This semester is over,” Ilhan said. “We lost many students. Each classroom lost two or three people, including some teachers.”

Elsewhere in the city, Outriders spotted several families moving all their home belongings onto trucks and into cars in preparation to move to new homes, some near and some far. Many vehicles on the highways in the region were packed with belongings.

One car we specifically remembered was packed with objects and had a child’s small tricycle tied down on the rooftop. Its tiny front-wheel peddles spun in the wind as the family drove towards their new or at least temporary home.

The losses caused by the earthquake are more than the sum of missing people and collapsed buildings. One shopkeeper barely kept himself from crying while speaking about his city with Outriders.

But some residents, like Omer Sanli, an elderly tailor, said they would persevere. Sanli wanted to stay in Osmaniye and fix his shop, which lost its windows to the tremors.

“All we need is some help,” Sanli said, looking at the building that housed his store. “Some repairs will be needed. We will make it through this.”

Syria / AleppoJandires

The rebel-held town of Jandaris, controlled by Turkish-backed militias, was more than a quarter reduced to rubble by the double quakes. It was one of the worst-hit areas in Syria, but no international aid had reached the town when I arrived there five days after the quakes. People burned whatever they could get their hands on to help them survive the bitter February cold. Food was barely available – none had come through the usual aid supply route, and many shops had been flattened.

The most startling sight was how thinly stretched and resourced the civil defence “White Helmets” volunteers were. In many of the worst-hit areas of Turkey, the sound of the rescue efforts were deafening as tens of thousands of international volunteers gridlocked the roads. There were ambulances, helicopters, search dogs, and machinery. In Jandaris, there was nothing.

The 3,000-strong White Helmets had to scrub through each wreckage of former buildings alone individually. They only had a handful of machinery and had begged local farmers to donate more. Entire streets were empty that had yet to be searched, with just a lone person picking through the rubble, brick by brick, looking for family members as they waited for the White Helmets to get to them. On the streets that the civil defence was actively working on, they operated with one machine and one truck to remove the debris.

People begged and screamed for help when foreign journalists entered.

“Why are our lives worth less than those in Turkey?” yelled 72-year-old Mohammed Hammo. “We can see the videos online of all the help they have over there. Why are we being left to die again?”

Civil defence team leader, Hassan Jabbar, said that the White Helmets had never seen destruction like this in over a decade of war. They desperately needed more heavy machinery to be brought into the territory, he said, before it was too late. Most of the screams that they had been able to hear over the past five days had already died away. The team was exhausted and desperately needed support.

The destruction was only likely to get worse, Jabbar added, with so many buildings still on the brink of collapse. Aftershocks are continuing and are likely to bring these buildings down.

As always – away from the destroyed areas — people in Jandaris were trying to continue everyday life, with their well-known resilience feeling more like a curse than a badge of honour.

For years, the tented community in northwest Syria has expanded. Driving through the northern Aleppo countryside, beautiful olive groves stretch for as far as the eye can see – mile after mile. Settlements of tents and families living beneath the trees break up their neat structure. The tented communities amid the olive groves are again growing as thousands more people become displaced in the war-torn countryside.

“They were all of my memories. Everything I owned”

Ahmad Ahmad, 30, grew up in the building that he was sleeping in when it was razed to the ground by the earthquake. All of his memories, all of his and his family’s history, were gone overnight. His heart truly broke when he found the body of his 20-day-old baby boy crushed by a brick. The rest of his family was alive, but both of his wives and two of his daughters were injured.

“Everything is destroyed and devastated. All of my memories. Everything I owned,” Ahmad said.

As they were jolted awake, Ahmad, his eight children and two wives tried to escape. They knew it was an earthquake, and they knew that they needed to scoop up the children and get outside. Before they could, the ceiling collapsed in on them. Ahmad’s mother and brother, who lived on the floor above them, managed to escape unharmed as their apartment only partially collapsed. Together, they managed to get their family out when daylight came.

In a state of panic, Ahmad rushed his family to the hospital. Doctors said his wives would soon be fine, as would his daughter. But they could do nothing for the baby boy whose fragile body had been instantly killed. His other daughter, they fear, has a bleed on the brain.

Sitting in a tent two streets over from where their home once stood, the family are now sheltering on the street reduced to rubble. Rebuilding is an impossibility, Ahmad says. How would they possibly pull together enough money to rebuild or even rent? He adds that his kids are too scared to go near buildings now anyway, so their foreseeable future will be in a tent — like many in the impoverished rebel-held northwest, even before the earthquake.

When I was in Jandaris five days after the earthquakes, finding a tent was like winning the lottery. According to local officials, some 4,000 families had been displaced by the quake, but the town had only been able to gather 1,200 families from local and Turkish aid groups.

Ahmad is squatting in someone else’s tent – friends had given him some better temporary shelter. When he returns, Ahmad doesn’t know how to keep his family warm through the bitterly cold winter. He hopes the two families can squeeze in together but doesn’t even logistically think they would fit.

A logistical nightmare

The northwest of Syria was a humanitarian disaster even before the earthquake. The rebel-held enclave of 4.5 million people has desperately relied on international aid to survive for years. Syrian President Bashar al Assad and his Russian allies have long opposed aid deliveries into the opposition territory, calling it an affront to their sovereignty. The UN managed to set up a huge mechanism in 2014 that delivered cross-border aid through four different crossings. Using its veto power at the UN Security Council, Russia has shut them down one by one, leaving just one available route for aid remaining through Turkey’s Bab al Hawa border crossing.

The route was already vulnerable. Russia’s demands meant that a vote had to take place every six months to keep the only border crossing open: the threat that Russia could shut down the only aid route to the humanitarian disaster was constantly looming over them.

Then, the earthquake hit. The UN said the road to Bab al Hawa was damaged, and aid delivery became a logistical nightmare. For almost a week, no international aid entered northern Syria as people went hungry and died underneath the rubble.

The only deliveries that crossed the Turkish border into Syrian territory were the bodies of dead Syrian refugees who had died under buildings in Turkey.

The aid has been a lifeline to over four million people who have been desperately in need for years. Disruption to the route hampered survival in the aftermath of the earthquake and meant that all of the usual aid deliveries were suspended. Stocks of food, baby milk and medication were running short in the middle of a natural disaster.

It took a full week after the earthquakes for the UN – in what they admit was a total failure – to discuss reopening the other border crossings to get life-saving aid in. Just days before I had crossed the Bab al Salamah border crossing – the road was perfectly intact and empty. There was no logistical reason for people to die without international support.

To not have to vote on another resolution, the UN sat down with Assad, who agreed to open two further crossings for aid, initially for three months. The move has sparked fear among Syrians that it could be the start of the international community bringing his isolated authoritarian regime back in from the cold.

By the time aid began to pass through the crossings, as Turkey’s search and rescue mission ended, Syrians decried that it was far too little or too late. Their complicated, protracted conflict had left them too complicated for any meaningful western support, yet again, and they had been abandoned.

Assad, and the international community, had put politics before aid for a week before it began to trickle in. Assad had insisted from the beginning that all aid should go directly through Damascus and in coordination with his government rather than across the Turkish border to the rebels. He said he wanted to help all Syrians, but his regime has a history of blocking aid going north to those in rebel-held territory.

Beginning her life as an orphan

Meanwhile, about 20 kilometres from there, in Afrin, Aya quickly became an international symbol of hope in the aftermath of the earthquake when a video of her rescue went viral online.

Her limp dusty body was passed from person to person as they tried to quickly get her to safety. Her umbilical cord could still be seen hanging, having just been cut minutes before.

Born underneath the rubble, she was found still attached to her dead mother’s umbilical cord some 10 hours after the quake. Neither of her parents had survived, and she began her life as an orphan. Her four siblings didn’t meet their new baby sister either, having died underneath the rubble.

In a hospital in Afrin five days later, I found Aya healthy and getting stronger by the minute. Her hand was still bandaged, but she was being well looked after and wearing an oversized diaper. Her release from the hospital to extended family was expected to come in the following days. She had come to the hospital bitter cold with bruises and scrapes, paediatrician Hani Maarouf said. She was in bad shape, and it was not clear if she would make a full and proper recovery.

With the help of the hospital, her condition quickly improved.

Before it was reduced to rubble, Aya never saw her first home or her hometown of Jandaris. The hospital quickly tried to bring her family. Khaled Radwan, the hospital manager, asked his wife to breastfeed the orphaned baby – which doctors say markedly improved her health. Aya, Khaled’s wife, had given birth to their first daughter just five months earlier.

Being born into the spotlight of foreign media came with its prices, both for Aya and the hospital. The Afrin health directorate on Wednesday decided to move the baby to a “safe location” after a kidnapping attempt on Tuesday evening. Khaled said an armed group had attempted to take her and injured him.

The hospital manager named the baby “Aya”, Arabic for ‘miracle’ or ‘an act of God’, after his wife.

Syria / IdlibIdlib

More than five million Syrians may be homeless after the quakes

On February 6, 2023, at 4:17 a.m. local time, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake rocked southeast Turkey.

As people slept in neighbouring Syria, in the northwest of the country, their houses collapsed. This is an area hit by the nearly 12-year conflict and refugee crisis.

Only two hours have passed since the earthquake, and volunteers of the Syrian Civil Defence, better known as the White Helmet, are trying to pull out the bodies of a man and his son who got stuck between the walls of their destroyed home in Idlib city centre.

Less than 12 hours after the first earthquake, a second one of 7.6 magnitudes rocked the same region. In Syria, the two earthquakes severely affected Aleppo and Idlib governorates.

The images captured by a drone show tragic scenes.

Survivors are trying to collect what little remains of their belongings under the rubble.

Meanwhile, some rescue teams are trying to rescue the people stuck under the rubble.

In Harem, Idlib, some neighbours have just rescued a child, and joy replaces for a few minutes the feeling of despair.

Not far from there, in Jindires, some children prepared themselves to be displaced by the Turkish Syrian border after their building was destroyed. This population is already suffering mass displacement and will have to find a home again.

More than five million Syrians may be homeless after these earthquakes, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

More than 5,800 deaths have been reported in war-torn Syria following the deadly earthquakes.

Turkey / AdanaAdana

Adana was among the least impacted provinces near the Feb. 6 earthquake epicentre, but it did lose hundreds of residents with the collapse of several high-rise apartment buildings.

When Outriders visited the sites of those wrecked apartments on Feb. 18, nearly all the rubble had been cleared by clean-up crews working at rapid speed, likely to make way for new residential developments.

At a nearby camp, about two dozen tents were erected by the nation’s emergency response agency, AFAD, and children cheerfully ran around a playground surrounded by the temporary encampments.

Ikmet Sokal, the father of several girls, who was not displaced but said the quakes damaged the bakery where he worked, said the residents of Adana were doing what they could to help harder-hit areas like Hatay and Gaziantep.

Noting many displaced people were moving to places like Adana and the neighbouring Mersin province, Sokal said one problem facing Adana was the lack of available apartments for rent.

“Since few houses are up for rent, the government places some people in tents. It’s going to be a difficult year,” Sokal said. “I hope we’ll get through this. God willing, Turkey will get through this.”

The rental dilemma was particularly felt by Gokcar Gungorur and his wife, who requested to remain unnamed. The couple shared a tent in the park and said they had one shower in the first 13 days after the earthquakes, adding that life was becoming unbearable without basic necessities and sanitation.

“We are now looking for a new home,” Gungorur said, “But the rent prices are high. I am a person who earns minimum wage (or about 8,500 Turkish liras/425 euros a month.).”

He continued, “The minimum rent prices around here are 8,000 a month … There is no possibility for us to stay in those houses. After paying rent, I would be left with 500 liras.”

Further aggravating the already stressful period, Gungorur said safety inspectors recently certified his home as undamaged, despite the presence of visible cracks in support columns, according to Gungorur.

“They say it’s okay to live there, but there are cracks in the plaster,” Gungorur said. “We stay in the tent because of fear. We have a difficult situation. A damaged building was reported as undamaged.”

Many will continue to face similar circumstances, struggling to find affordable rent while at the same time living in subpar conditions. Yet throughout, Adana will likely become a logistics hub to serve impacted areas with humanitarian aid for the coming period.

Turkey / AdıyamanAdıyaman

After Hatay, Outriders observed the second-highest number of collapsed buildings in Adiyaman, a province northeast of the earthquake’s epicentre that witnessed some of the highest death counts resulting from the disaster.

With just 270,000 people, the central city of Adiyaman, which bears the same name, is relatively small and therefore devastated following the massive tremors.

Much of its infrastructure and buildings will need to be rebuilt, and Turkish President Erdogan promised to do that during his post-quake visit to the city, setting the ambitious goal of housing displaced residents in newly built homes within one year.

Some locals saw this as a sign of hope for better times to come and that their lives would one day return to normal, but others remained outraged by what they saw as an inadequate and slow state response in the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes.

Many Adiyaman residents said state officials and emergency response crews came too late to save their loved ones, who remained trapped under the rubble for days.

Some locals complained they paid taxes and sent their sons to military service; they also voted in favour of Erdogan’s ruling party in previous elections. But when they needed the state most, they said no one showed up for days.

Many survivors stay in tent encampments throughout the city, like Abdulrahman Demir, who lost his home to the earthquakes. Speaking from his encampment, Demir said the area lacked necessities and called for more aid towards the city.

“Electricity, food, supplies, shoes, we need everything,” Demir said.

Yet some families remained without tents when Outriders visited the city on Feb. 17. Speaking from inside a shattered storefront across the street from her collapsed home, Nurdan Altinkaynak held her 11-month-old daughter and said she had been sleeping outdoors since Feb. 6 with her baby, teenage son and husband, all without a tent in freezing winter temperatures.

“God protected my baby,” Altinkaynak said, detailing how her family was rescued from their collapsed home, but she noted sadly that her mother did not get out alive. Her husband began to cry as we talked.

After some sensitive moments, Outriders asked what the Altinkaynak family would do next. The teenage son said they were preparing to move in with relatives in Mardin, a province in southeast Turkey.

Until then, they would continue to get by on food provided by the municipality, but with slim chances to find even temporary shelter in Adiyaman.

Turkey / GaziantepGaziantep

The southern Turkish town of Gaziantep is just 32 km from the epicentre of the earthquake in Kahramanmaraş

Gaziantep’s city centre also had many encampments in city parks and squares. The main displaced population there was composed of Syrian refugees, who said their homes were no longer safe to inhabit.

This town is only about 60 km from the border with Syria.

Outriders observed municipality police distributing food and soup to Syrians in tent encampments. Still, conditions remained tough as news reports indicated refugee populations in Turkey faced more discrimination following the earthquakes. Many Syrians were blamed for looting stores amid the chaos in the earthquake aftermath.

Long-accustomed to being scapegoats for the nation’s problems, Syrians interviewed by Outriders in Gaziantep said they had received many donations and felt relatively safe, despite often discriminatory rhetoric at the national level.

Turkey / GaziantepNurdagi

While parts of its historic castle crumbled to the ground, Gaziantep’s city centre was spared the worst damage on February 6, unlike several of the province’s smaller cities, some of which were almost entirely destroyed by the earthquakes.

Not far from the fault lines, the cities of Nurdagi and Islahiye were devastated. As a result, both cities’ populations, about 41,000 in Nurdagi and 67,000 in Islahiye, were nearly all displaced. Most were staying with relatives in nearby cities or tent encampments, built quickly following the earthquakes, in the cities’ public squares and parks.

When Outriders visited Nurdagi on Feb. 13, many families lived in tents as some waited for their loved ones to be dug out of the rubble. No habitable building was visible in the city centre, with the standing apartment buildings visibly cracked or missing entire sections.

At the same time, less depressing scenes were observed as children participated in organised activities in the city’s parks. Meanwhile, adults and emergency aid workers stood in lines for hot meals served by food trucks bearing the logos of the various municipalities and restaurants that sent aid from around the country.

In the cold of winter, in areas without running water, electricity, gas or heat at the time, those warm soups and doner kebabs could be compared to lifesavers at sea for the way they could keep the mind and body afloat during hard times.

Yet challenges remained. At the encampment in central Nurdagi, Outriders observed just four portable bathrooms – two for women, two for men – for hundreds of people.

The sanitary and hygienic conditions have likely improved since the initial earthquake aftermath. Still, prolonged periods without access to basic hygienic standards can quickly lead to the spread of diseases among displaced populations, which would then worsen already difficult conditions.

Turkey / HatayIskenderun & Antakya

Hatay looks like an area ravaged by years of war, and only the damage came in one day.

There are few ways to describe places like Iskenderun on the Mediterranean coast, whose port remained in flames days after the tremors as burning chemical substances sent a plume of black smoke over the collapsed city centre.

In worse condition is Antakya, where few undamaged buildings remain on its central thoroughfare, now a scene of dust clouds and search crews working at all hours to dig into mountains of rubble. Some neighbourhoods have been completely erased as many residents remain missing.

Hatay hosts the most extensive damage and loss of life following the Feb. 6 earthquakes.

The province’s 1.69 million residents remain in shock following the instant destruction of their unique, diverse and historical cities.

Many are currently displaced, living in emergency tent shelters or have left to stay with friends and relatives elsewhere.

At the same time, some Hatay residents continue to stand by piles of rubble, waiting for their loved ones to be recovered from collapsed buildings, which killed a yet-to-be-confirmed number of victims.

The final death toll for Hatay alone is likely to be in the tens of thousands. Until all missing people are accounted for, the pain experienced by their friends and family remains too sharp for words.

Beyond the loss of life and infrastructure, the damage to Hatay cuts deep also because the province represents a meeting point for many cultures, religions and historical lines, comparable to few other areas in the Middle East.

Now the members and meeting places of those communities, the churches, synagogues and mosques are in ruins.

The citizens contemplate their next steps, knowing reconstruction will take years.

Though one of the oldest churches in Christianity, the Church of Saint Peter in Antakya, was reportedly not damaged as it is carved into the side of a mountain, Outriders could not verify its status as the site was closed to the public immediately after the earthquakes.

With the necessary resources, infrastructure and aid, Hatay residents interviewed by Outriders said they would return to their hometowns and hoped to continue their ties with one of the oldest centres of human civilization.

Over its long history, Hatay has endured many traumas, wars, plagues and disasters.

Following the initial mourning period and earthquake reconstruction efforts, locals plan to continue the area’s tradition to persevere and thrive again.

Turkey / KahramanmaraşKahramanmaraş

After Hatay and Adiyaman, Outriders observed the third-highest number of collapsed buildings in Kahramanmaras.

Many streets in the city centre are blocked by the remains of large office towers and apartment buildings that crumbled into massive piles of concrete, now slowly being removed, one scoop at a time, by armies of excavators.

Sadly, much of Kahramanmaras’ Ottoman cultural heritage is among the wreckage, including a historic covered market known as the Maras Bazaar and the 15th-century Maras Grand Mosque, whose unique, wooden-top minaret was lost to the earthquakes. (The city was historically known as Maras).

Beyond landmarks, Kahramanmaras suffered extensive damage in its residential neighbourhoods, which in the city centre are a mix of picturesque wood and mud-walled Ottoman homes and DIY dwellings known as ‘gecekondu’ or the Turkish word for slums. In these residential areas, the highest number of victims continue to be found.

When Outriders toured the city on Feb. 14, many residents of Kahramanmaras’ historic centre salvaged whatever items they could from their collapsed homes. A young man named Yasar, who withheld his last name, was spotted carrying a microwave across a fallen concrete rooftop and passing it down to his cousins.

Yasar then returned across the same slanted rooftop to reach the cracked balcony of his collapsed family home and climbed inside. A few moments later, he appeared again, this time with jars of pickles and tomato sauces, apparently emptying out the kitchen.

“We are taking anything that’s worth keeping,” Yasar said, adding his family moved in with relatives in a house that did not collapse.

Asked what he would do next, Yasar was at a loss for words, saying: “Everyone has left my hometown. They had to get shelter somewhere else.”

Ayse Kaya, another Kahramanmaras resident, echoed the sentiments and spoke to Outriders while her husband salvaged goods from his collapsed childhood home.

“Life is finished here. There is nothing left,” Kaya said.

Earthquake victims across the region often repeated her words. In their initial grief, many people interviewed by Outriders expressed doubt their lives would ever return to normal or the way they used to live before the earthquakes.

And how could they? Tens of thousands of people lost their lives after Feb. 6, and entire neighbourhoods lost their markets, streets, meeting places and traditions. Kaya recalled memories from her husband’s family home among the sad moments.

“We used to like this house so much. It was always cool in the summer,” she said.

Turkey / KilisKilis

Kilis, a small province between Gaziantep and the Syrian border, did not experience significant damage during the Feb. 6 earthquakes. Still, their aftereffects led to the temporary closure of Kilis’s border gate, an essential route for humanitarian aid flowing into Syria.

More than 4 million Syrians in the nation’s northwest rely on supplies and aid from Turkey for subsistence. Due to severe infrastructure damage in Turkey, most area residents were left without government support or humanitarian assistance during initial earthquake response efforts.

Some United Nations and World Food Programme aid convoys entered northwest Syria from a Hatay border crossing in the first week following the earthquakes. Still, the Kilis border gate did not reopen until Feb. 14.

Isolated from the rest of Syria after 12 years of civil war, several thousands of Syrians in northwest territories died during and after the earthquakes. However, many lives were spared because much of the displaced population lived in tents instead of apartment buildings at the time of the tremors.

Having experienced trauma after trauma, some Syrians inside and outside the region often express feelings that the world has forgotten them. Responding exactly to those sentiments, Luqman Vania and Abrar Khan, two humanitarian workers with One Nation UK, a non-profit organization, crossed the Kilis border gate on Feb. 16 carrying supplies with their hands.

Outriders caught up with them just before they crossed over.

“In Syria, logistically, it’s significantly harder to get aid across, and I think the Syrians are for sure feeling that,” Vania said as he carried a hydraulic lift, which works like a car jack. It lifts or supports fallen concrete slabs and is an essential tool for search-and-rescue efforts.

“We’re taking this because I was speaking to those on the other side, and they were saying we need heavy machinery, that kind of stuff, and unfortunately, we can’t take it across,” Khan said. “But this, I thought we could get it from the UK and take it across. It’s just a small gesture from us to help on the Syria side.”

This a possibly small but much-needed gesture, as infrastructure in northwest Syria was significantly damaged by earthquakes, and its population is now at high risk of food and water-borne diseases due to inadequate sanitation conditions.

Critically, northwest Syria has been experiencing a cholera outbreak since November 2022. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control warned public health conditions could worsen following the earthquakes without the necessary humanitarian supplies that flow through border gates like the one in Kilis.

Turkey / OsmaniyeOsmaniye

Ibrahim Ilhan, a teacher in Osmaniye, estimates half of the city’s 200,000 residents will move elsewhere in the aftermath of the Feb. 6 earthquakes. He plans to be in the remaining half but knows hard days are ahead for his hometown, where about one kilometre of the central avenue linking the historic centre to the train station is in disrepair.

Locals say nearly all high-rise buildings on this stretch, called Hasan Cenet Avenue, will need to be demolished and replaced with new structures. Ilhan plans to remain in the area as he stays with his wife’s family in a nearby village for the current period.

“We don’t have another place to go other than Osmaniye,” Ilhan said. “We will stay here.”

He spoke to Outriders next to his apartment on Hasan Cenet Avenue. It was located in a high-rise building that now bears visible cracks in its exterior. According to Ilhan, a worse fate hit an identical high-rise apartment next door, which collapsed in the first five seconds of the earthquake.

As a result, more than 100 people died, including many neighbours he knew. He said only five people were rescued from the building’s upper floors.

Shaking his head while looking at the rubble where so many lost their lives less than two weeks earlier, Ilhan said the school was suspended, and he wasn’t sure classes would resume considering the high death toll.

“This semester is over,” Ilhan said. “We lost many students. Each classroom lost two or three people, including some teachers.”

Elsewhere in the city, Outriders spotted several families moving all their home belongings onto trucks and into cars in preparation to move to new homes, some near and some far. Many vehicles on the highways in the region were packed with belongings.

One car we specifically remembered was packed with objects and had a child’s small tricycle tied down on the rooftop. Its tiny front-wheel peddles spun in the wind as the family drove towards their new or at least temporary home.

The losses caused by the earthquake are more than the sum of missing people and collapsed buildings. One shopkeeper barely kept himself from crying while speaking about his city with Outriders.

But some residents, like Omer Sanli, an elderly tailor, said they would persevere. Sanli wanted to stay in Osmaniye and fix his shop, which lost its windows to the tremors.

“All we need is some help,” Sanli said, looking at the building that housed his store. “Some repairs will be needed. We will make it through this.”

Syria / AleppoJandires

The rebel-held town of Jandaris, controlled by Turkish-backed militias, was more than a quarter reduced to rubble by the double quakes. It was one of the worst-hit areas in Syria, but no international aid had reached the town when I arrived there five days after the quakes. People burned whatever they could get their hands on to help them survive the bitter February cold. Food was barely available – none had come through the usual aid supply route, and many shops had been flattened.

The most startling sight was how thinly stretched and resourced the civil defence “White Helmets” volunteers were. In many of the worst-hit areas of Turkey, the sound of the rescue efforts were deafening as tens of thousands of international volunteers gridlocked the roads. There were ambulances, helicopters, search dogs, and machinery. In Jandaris, there was nothing.

The 3,000-strong White Helmets had to scrub through each wreckage of former buildings alone individually. They only had a handful of machinery and had begged local farmers to donate more. Entire streets were empty that had yet to be searched, with just a lone person picking through the rubble, brick by brick, looking for family members as they waited for the White Helmets to get to them. On the streets that the civil defence was actively working on, they operated with one machine and one truck to remove the debris.

People begged and screamed for help when foreign journalists entered.

“Why are our lives worth less than those in Turkey?” yelled 72-year-old Mohammed Hammo. “We can see the videos online of all the help they have over there. Why are we being left to die again?”

Civil defence team leader, Hassan Jabbar, said that the White Helmets had never seen destruction like this in over a decade of war. They desperately needed more heavy machinery to be brought into the territory, he said, before it was too late. Most of the screams that they had been able to hear over the past five days had already died away. The team was exhausted and desperately needed support.

The destruction was only likely to get worse, Jabbar added, with so many buildings still on the brink of collapse. Aftershocks are continuing and are likely to bring these buildings down.

As always – away from the destroyed areas — people in Jandaris were trying to continue everyday life, with their well-known resilience feeling more like a curse than a badge of honour.

For years, the tented community in northwest Syria has expanded. Driving through the northern Aleppo countryside, beautiful olive groves stretch for as far as the eye can see – mile after mile. Settlements of tents and families living beneath the trees break up their neat structure. The tented communities amid the olive groves are again growing as thousands more people become displaced in the war-torn countryside.

“They were all of my memories. Everything I owned”

Ahmad Ahmad, 30, grew up in the building that he was sleeping in when it was razed to the ground by the earthquake. All of his memories, all of his and his family’s history, were gone overnight. His heart truly broke when he found the body of his 20-day-old baby boy crushed by a brick. The rest of his family was alive, but both of his wives and two of his daughters were injured.

“Everything is destroyed and devastated. All of my memories. Everything I owned,” Ahmad said.

As they were jolted awake, Ahmad, his eight children and two wives tried to escape. They knew it was an earthquake, and they knew that they needed to scoop up the children and get outside. Before they could, the ceiling collapsed in on them. Ahmad’s mother and brother, who lived on the floor above them, managed to escape unharmed as their apartment only partially collapsed. Together, they managed to get their family out when daylight came.

In a state of panic, Ahmad rushed his family to the hospital. Doctors said his wives would soon be fine, as would his daughter. But they could do nothing for the baby boy whose fragile body had been instantly killed. His other daughter, they fear, has a bleed on the brain.

Sitting in a tent two streets over from where their home once stood, the family are now sheltering on the street reduced to rubble. Rebuilding is an impossibility, Ahmad says. How would they possibly pull together enough money to rebuild or even rent? He adds that his kids are too scared to go near buildings now anyway, so their foreseeable future will be in a tent — like many in the impoverished rebel-held northwest, even before the earthquake.

When I was in Jandaris five days after the earthquakes, finding a tent was like winning the lottery. According to local officials, some 4,000 families had been displaced by the quake, but the town had only been able to gather 1,200 families from local and Turkish aid groups.

Ahmad is squatting in someone else’s tent – friends had given him some better temporary shelter. When he returns, Ahmad doesn’t know how to keep his family warm through the bitterly cold winter. He hopes the two families can squeeze in together but doesn’t even logistically think they would fit.

A logistical nightmare

The northwest of Syria was a humanitarian disaster even before the earthquake. The rebel-held enclave of 4.5 million people has desperately relied on international aid to survive for years. Syrian President Bashar al Assad and his Russian allies have long opposed aid deliveries into the opposition territory, calling it an affront to their sovereignty. The UN managed to set up a huge mechanism in 2014 that delivered cross-border aid through four different crossings. Using its veto power at the UN Security Council, Russia has shut them down one by one, leaving just one available route for aid remaining through Turkey’s Bab al Hawa border crossing.

The route was already vulnerable. Russia’s demands meant that a vote had to take place every six months to keep the only border crossing open: the threat that Russia could shut down the only aid route to the humanitarian disaster was constantly looming over them.

Then, the earthquake hit. The UN said the road to Bab al Hawa was damaged, and aid delivery became a logistical nightmare. For almost a week, no international aid entered northern Syria as people went hungry and died underneath the rubble.

The only deliveries that crossed the Turkish border into Syrian territory were the bodies of dead Syrian refugees who had died under buildings in Turkey.

The aid has been a lifeline to over four million people who have been desperately in need for years. Disruption to the route hampered survival in the aftermath of the earthquake and meant that all of the usual aid deliveries were suspended. Stocks of food, baby milk and medication were running short in the middle of a natural disaster.

It took a full week after the earthquakes for the UN – in what they admit was a total failure – to discuss reopening the other border crossings to get life-saving aid in. Just days before I had crossed the Bab al Salamah border crossing – the road was perfectly intact and empty. There was no logistical reason for people to die without international support.

To not have to vote on another resolution, the UN sat down with Assad, who agreed to open two further crossings for aid, initially for three months. The move has sparked fear among Syrians that it could be the start of the international community bringing his isolated authoritarian regime back in from the cold.

By the time aid began to pass through the crossings, as Turkey’s search and rescue mission ended, Syrians decried that it was far too little or too late. Their complicated, protracted conflict had left them too complicated for any meaningful western support, yet again, and they had been abandoned.

Assad, and the international community, had put politics before aid for a week before it began to trickle in. Assad had insisted from the beginning that all aid should go directly through Damascus and in coordination with his government rather than across the Turkish border to the rebels. He said he wanted to help all Syrians, but his regime has a history of blocking aid going north to those in rebel-held territory.

Beginning her life as an orphan

Meanwhile, about 20 kilometres from there, in Afrin, Aya quickly became an international symbol of hope in the aftermath of the earthquake when a video of her rescue went viral online.

Her limp dusty body was passed from person to person as they tried to quickly get her to safety. Her umbilical cord could still be seen hanging, having just been cut minutes before.

Born underneath the rubble, she was found still attached to her dead mother’s umbilical cord some 10 hours after the quake. Neither of her parents had survived, and she began her life as an orphan. Her four siblings didn’t meet their new baby sister either, having died underneath the rubble.

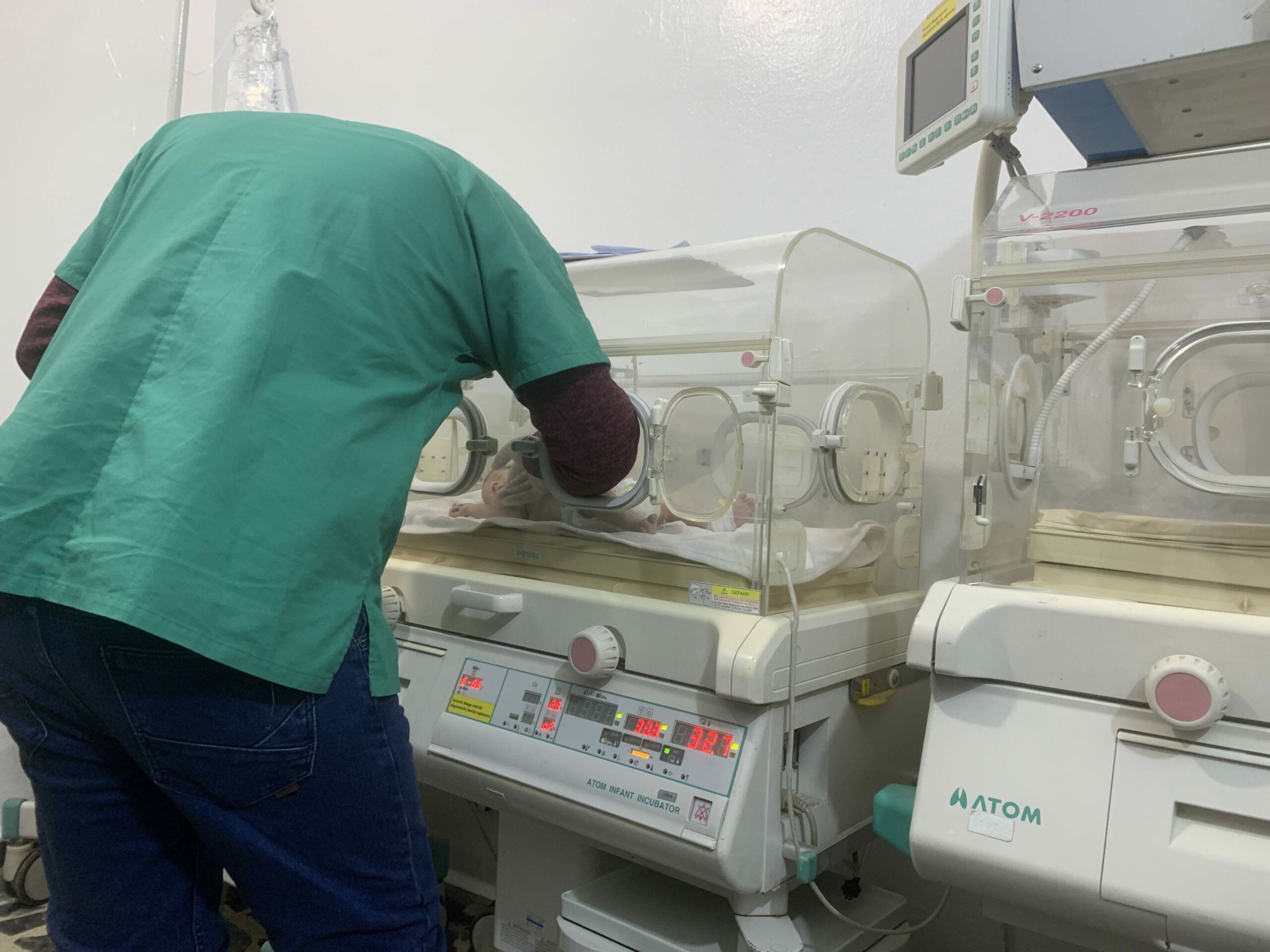

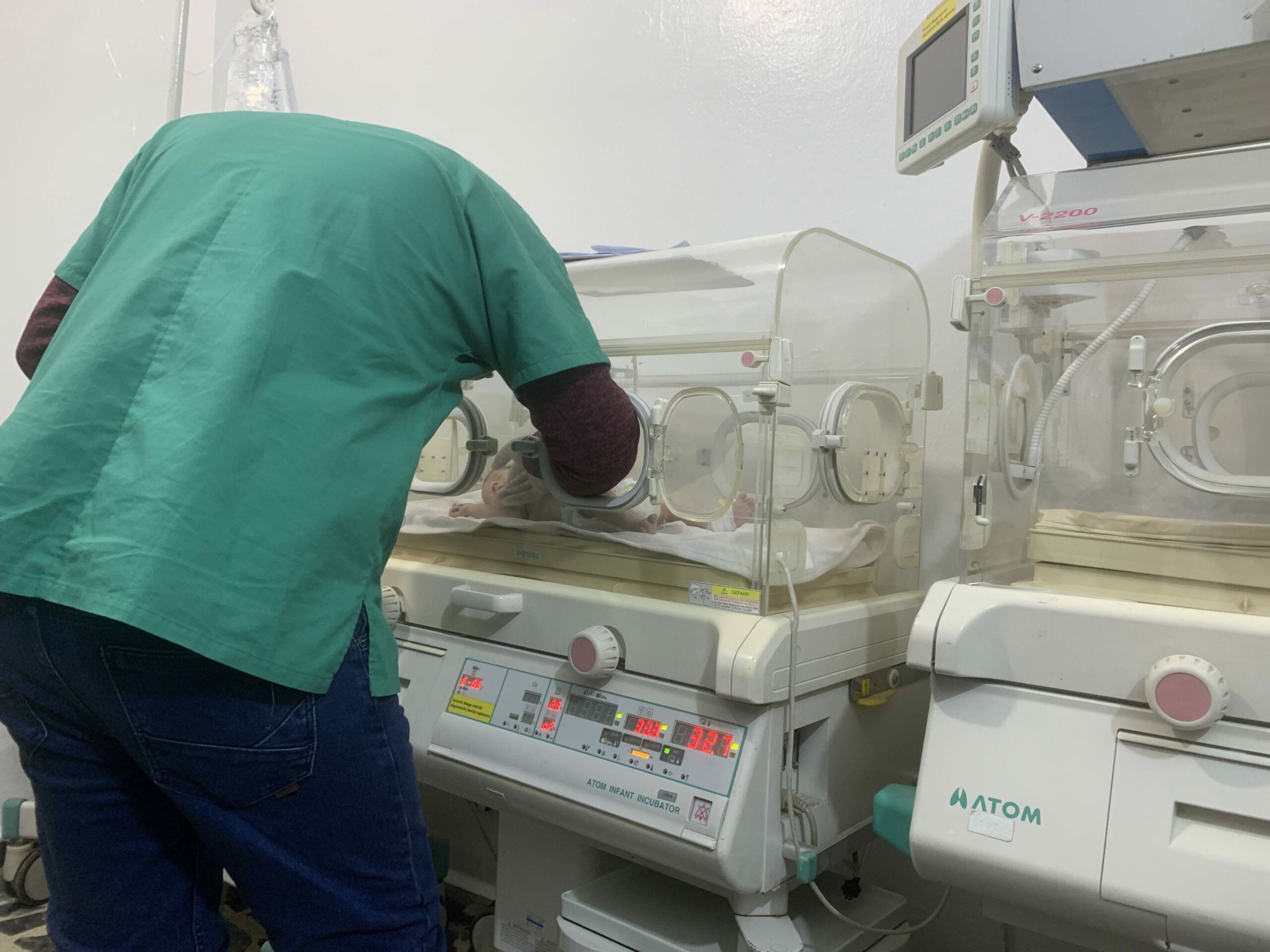

In a hospital in Afrin five days later, I found Aya healthy and getting stronger by the minute. Her hand was still bandaged, but she was being well looked after and wearing an oversized diaper. Her release from the hospital to extended family was expected to come in the following days. She had come to the hospital bitter cold with bruises and scrapes, paediatrician Hani Maarouf said. She was in bad shape, and it was not clear if she would make a full and proper recovery.

With the help of the hospital, her condition quickly improved.

Before it was reduced to rubble, Aya never saw her first home or her hometown of Jandaris. The hospital quickly tried to bring her family. Khaled Radwan, the hospital manager, asked his wife to breastfeed the orphaned baby – which doctors say markedly improved her health. Aya, Khaled’s wife, had given birth to their first daughter just five months earlier.

Being born into the spotlight of foreign media came with its prices, both for Aya and the hospital. The Afrin health directorate on Wednesday decided to move the baby to a “safe location” after a kidnapping attempt on Tuesday evening. Khaled said an armed group had attempted to take her and injured him.

The hospital manager named the baby “Aya”, Arabic for ‘miracle’ or ‘an act of God’, after his wife.

Syria / IdlibIdlib

More than five million Syrians may be homeless after the quakes

On February 6, 2023, at 4:17 a.m. local time, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake rocked southeast Turkey.

As people slept in neighbouring Syria, in the northwest of the country, their houses collapsed. This is an area hit by the nearly 12-year conflict and refugee crisis.

Only two hours have passed since the earthquake, and volunteers of the Syrian Civil Defence, better known as the White Helmet, are trying to pull out the bodies of a man and his son who got stuck between the walls of their destroyed home in Idlib city centre.

Less than 12 hours after the first earthquake, a second one of 7.6 magnitudes rocked the same region. In Syria, the two earthquakes severely affected Aleppo and Idlib governorates.

The images captured by a drone show tragic scenes.

Survivors are trying to collect what little remains of their belongings under the rubble.

Meanwhile, some rescue teams are trying to rescue the people stuck under the rubble.

In Harem, Idlib, some neighbours have just rescued a child, and joy replaces for a few minutes the feeling of despair.

Not far from there, in Jindires, some children prepared themselves to be displaced by the Turkish Syrian border after their building was destroyed. This population is already suffering mass displacement and will have to find a home again.

More than five million Syrians may be homeless after these earthquakes, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

More than 5,800 deaths have been reported in war-torn Syria following the deadly earthquakes.

The Twin Quakes project by Outriders has been developed by several journalists who have toured the affected cities in Turkey and Syria during the two weeks following the earthquake on February 6th, 2023, as well as the editors, translators, designers and developers who have worked on it.

All magnitude scales represented in this interactive article are based on measurements by the US Geological Survey. The figures correspond to the Modified Mercalli intensity scale (MMI) of the Initial quake on February 6th, 2023, at 4:17 a.m. (local time).

A PROJECT BY:

Diego Cupolo - articles, photos and video (Antakya, Iskenderun, Gaziantep, Nurdagi, Adyaman, Kilis, Kahramanmaraş and Osmaniye - Turkey)

Abbie Cheeseman - articles, photos and video (Jindires and Afrin - Syria)

Mohamad Daboul - drone footage from Syria

Tom Nicholson - drone footage (Adıyaman, Dogansehir and Hatay - Turkey)

Pepigin Nagtzaam, drone footage (Kahramanmaraş - Turkey)

Arkadiusz Sołdon - design

Piotr Kliks - web development

Grzegorz Kurek - translation

Lola García-Ajofrín - coordination

Produced by Outriders