Anger has reached some of the smallest towns across Belarus. So has violence, unseen here before. As Belarusians feel they are the majority, the president is creating a powder keg.

Hantsavichy, a small town in the Brest region, had never seen a political protest before. But it was the local police brutality that shocked local residents.

Ihar Dulik was on his way home the evening of 20 June when he noticed a friend in the city’s central square. The 45-year-old craftsman stopped and got out of his car when he heard someone shouting. Dulik pulled out his smartphone and began filming the police as they violently arrested two reporters.

At that moment, the police approached Dulik, grabbed him from behind, and started beating him. When he was face-down on the ground, one of the officers dug his knee into his neck and kept it there.

“I told the police I couldn’t breathe, but they kept beating me with their fists and legs,” an astonished Dulik said several days later. He was taken to a detention centre and ended up in a hospital with a kidney contusion and a concussion.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

When Dulik parked his car in downtown Hantsavichy, the police had already had brutally dispersed the protest. In videos taken by onlookers, the officers shove people onto the pavement, dragging them by the hair and handcuffing them.

Hantsavichy, a city of less than 14,000 people, is best known for housing the Volga radar, a Russian strategic military object. But as police officers used the neck restraint against at least two residents, the local media quickly dubbed it the “Belarusian Minneapolis.”

A Belarusian uprising

The protest in Hantsavichy was livestreamed by local journalists. The video shows a mere 20 people standing in silence in front of the city’s executive committee, observed by the ubiquitous Lenin. They clapped with hesitation when cars occasionally honked in support. It was Saturday. Some people came with their children.

This was one of many “solidarity chains” across Belarus, opposing the arrests of presidential hopefuls and activists. It might have gone unnoticed if not for what was some of the most acute police violence in the country.

“They brought 40 officers from the city police, the department for security, and traffic patrol,” says Aliaksandr Pazniak, a reporter with Hantsavicki Chas, a local independent newspaper, who managed to organize the stream. He was punched in the face and on the head and body, as he reported on air. Siarhei Bahrou, a cameraman and photographer, received a 15-day jail sentence.

It unleashed fury across town. “I held a rank of praporshchik during the Soviet times, I wore a uniform myself, so now I feel ashamed by the police actions,” says Anatol Valoshchyk, 58, the artistic director and chief conductor at the Hantsavichy House of Culture, a local official institution.

Everyone I spoke with criticised the police brutality. “A few days ago, I saw one of the officers in a grocery store, and I didn’t know how to behave. I feel no respect for the police,” says Kaciaryna, 27, who was at the rally but managed to avoid arrest.

Local social networking groups and chats have come out in support of the jailed cameraman, publishing avatars that read “We are Bahrou.” Residents donated money to the newspaper to help pay off the fines imposed on those detained. It’s a tight-knit community; people know one another.

For many, an abrupt attack on residents has become uniquely personal. “I was not active before, but now I’ve turned to politics,” says Maksim Amelyanovich, 33, a leading specialist at Modul, one of the few manufacturing firms in Hantsavichy. Right after the protest, he and his wife, Maryia Burvan, decided to collect signatures to become members of a local election commission. They were denied due to their “opposition views,” explains Burvan.

But their journey from indifference to active citizen participation was not long.

Most epic failure

People had reasons to protest. Hantsavichy is one of the poorest cities in the region. Men often leave to work in neighbouring Russia and Poland.

This is not unique across Belarus. There is anger, and a kind of spiritual fatigue that has reached even the smallest towns. Having a faltering economy was bad enough, but the bungled response to coronavirus was the last straw.

Aleksandr Lukashenko, who has ruled Belarus since 1994, is hardly alone in being ostracised for mishandling the coronavirus crisis. The comparison is crucial, though. Belarusians assess their government’s reaction as one of the most insufficient in the world. They believe the country’s leadership has been indifferent and incompetent.

And then there’s the economy. During his quarter of a century in power, Lukashenko has faced sporadic protests linked to worsening economic and social conditions. This spring, however, sociologists noted people’s perception of their well-being was the lowest in 20 years.

Protests had swept the country in 2017, despite more favorable assessments. What is different, explains Minsk-based political analyst Aliaksandr Klaskouski, is that three years ago, protesters demanded that Lukashenko cancel a tax on the unemployed. “Today, they don’t put any hopes in a president. They just want to change the man at the top,” says Klaskouski, head of analytical projects at independent news agency Belapan.

Many blame Lukashenko for the recession, low salaries, and lousy pensions. A price to pay for a dominant leader who singlehandedly steers the economy. It is clear that Lukashenko, who can no longer run for reelection trumpeting economic achievement, will rely on his autocratic, brutally repressive version of law and order. He hints that he can act like former Uzbek president Islam Karimov during the 2005 Andijan massacre, which left hundreds dead.

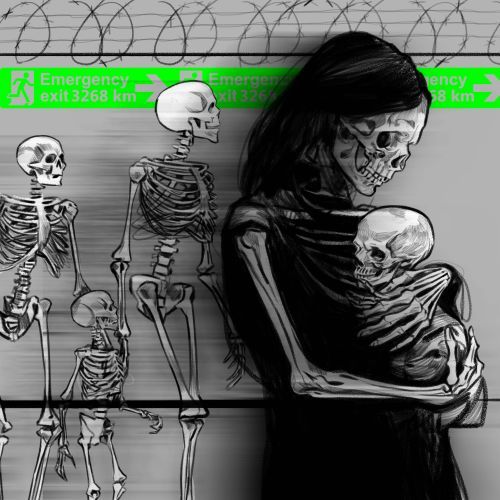

But the reasons for discontent will not disappear. The day after the 9 August election, Lukashenko will not transform his epic failures into spectacular accomplishments. Police batons will not bring back people’s love. Instead, Lukashenko is creating a powder keg.

When neighbours beat neighbours

This tension was already visible on 19 June in Molodechno, a city of less than 100,000, some 70 kilometres from Minsk. Protesters clashed with the police, trying to defend a man who was brutally arrested. An officer pulled his handgun, which scared people away. The Interior Ministry later said the gun simply slipped out of a holster. Many did not believe it.

The human capacity for patience and endurance, in the face of blatant injustice, is not without limits. Unlike their big city counterparts, members of the local police force are often neighbours. They are under immense pressure. In Hantsavichy, some officers and even their wives had to delete their social media accounts when their names and pictures were circulated, residents told me.

Aliaksandr Bondar, 33, who lives in Poland and came to his hometown for vacation, says he was among the first detained in Hantsavichy. “When I was taken to a police car, there was an officer inside. His colleagues asked him to help with arrests, but he stayed in the car.” The officer silently refused to detain people, according to Bondar.

Nevertheless, the siloviki, military and law enforcement services, remain one of the pillars of the house that Lukashenko built. We are far from a breakdown of the old power structures. But the mere fact that banker Viktar Babariko and former presidential aide Valery Tsepkalo intended to oppose the president in the election can be a sign. They immediately gained popularity, so they were denied registration as candidates. Doubting the loyalty of his ministers, Lukashenko recently reshuffled the government.

Doubts about the system

What is certainly new is anger among those who were previously silent: popular public figures. At least the scale of it is new. Sportsmen and Olympic athletes, musicians, showmen, actors, and journalists at pro-government TV channels expressed their solidarity with those detained. It has cost many their jobs.

Anton Martynenko, a TV anchor at the national channel STV, criticised police violence on his Instagram. His bosses immediately called him and told him to either delete his posts or leave the channel.

“I knew what consequences my criticism would have, because you don’t mess with the Belarusian state,” Martynenko told me. “But years of self-censorship were enough.” He quit STV, where he had worked for 12 years. He says that while the channel’s directors called him a “traitor,” his colleagues privately supported him. He believes that “moods are changing.”

Arciom Hackevich, 23, sees many of his friends becoming politically involved since recent arrests. He was himself brutally detained by plainclothesmen while waiting outside a café in central Minsk. He calls it “kidnapping” and believes it was a sort of preventive measure to scare others.

So far, it has had the opposite effect. Over three days in June, more than 360 people were detained in nearly 20 cities and towns. These were not only opposition activists in Minsk, who often faced repression. A deaf man; a pregnant woman; an oncologist; buyers waiting in line outside a gift shop; cyclists; random passers-by; a man roller skating. Their relatives and friends have been left in doubt about the lawfulness of the system.

“Since my son was cruelly beaten and arrested for nothing, does it mean the same happened to all those detained across the country?” asks Lidia Dulik, 69, whose son was beaten by the police in Hantsavichy. Although she believes the brutal attack on her son was an attempt to harm Lukashenko’s reputation, she has turned to independent media for information.

“We are 97%”

The pandemic has created one clear winner: those who spread information. Of course, Lukashenko’s sheer repetition of falsehoods about the coronavirus did not make people less worried. And so they turned to bloggers and journalists.

“Independent outlets and social media established a virtual monopoly over people’s minds,” says sociologist Andrei Vardamatski, head of Belarusian Analytical Workshop, a Warsaw-based polling organisation. People felt cheated. The inconsistency between the information offered by the government and people’s experiences during the pandemic contributed to killing trust in state media. And, well, in Lukashenko himself.

Blogger Siarhei Tsikhanouski built his political capital on interviewing people across the country for his YouTube channel. He transformed his views into real support and protests. He and other popular and influential bloggers are now in jail.

Bloggers and journalists destroyed the greatest myth of the official propaganda: The capital may protest, but the regional folks are the president’s real supporters. When these folks started talking, the rest of the country saw that this isn’t always true. If a tractor driver from the small town of Khoiniki publishes a video calling on election commissions to prevent vote rigging and “stop dictatorship,” it garners nearly 100,000 views.

That’s why a meme putting the incumbent president’s approval rating at 3 percent is so popular: perhaps for the first time, Belarusians who want change consider themselves the new majority. It won’t be easy to convince them otherwise when the election results are announced.