“I was beaten only once. Probably it was my fault – I was rude to the officer,” 20-year-old Yulia said. She spent three days in the detention center on Akrestsin Street after being detained the night following the presidential election on 9 August. She and thousands of others had converged in central Minsk to demand the reversal of the election victory claimed by President Alyaksandr Lukashenka. They gathered peacefully to protest against what many said was election fraud.

“They threw me into a police van, took me to the police station, kept me there outside until morning and then they took me to the detention center.” Yulia was not charged or put on trial. She spent three days in an overcrowded cell with almost no food or clean drinking water. Women in the cell had to take turns sleeping because there were not enough beds. On the third day, she was released without explanation.

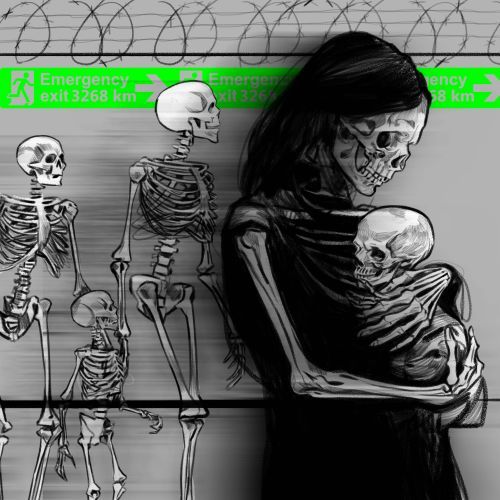

Thousands of stories like this have circulated since then. Within days after the election, the Akrestsin detention center became synonymous with torture: people were brutally beaten and tortured there for participating in peaceful protests or for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Torture on so massive a scale has receded, but complaints of cruel treatment continue to appear.

On 1 September, the UN human rights agency announced that its experts had received 450 reports of torture and cruel treatment in Belarus since 9 August. On 13 November — by which time the total number of detainees was estimated to have reached 25,000 — the agency reminded Belarusian authorities “of the absolute prohibition of torture and the need for thorough, independent and impartial investigations into all allegations of human rights violations, with a view to ensuring accountability, ensuring access to an effective remedy for victims and preventing a further deterioration of the situation.” Around that time, the Telegram channel Nexta Live relayed an estimate of 1,000 complaints about the brutal treatment detainees experienced in just the first five days of the protests.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

Not everyone was tortured at Akrestsin. Some people were bullied during their arrest, while being transported to a police station, in police stations, and in other detention centers where police started sending the detainees when space at Akrestsin ran out. The official capacity of the “isolation center for offenders,” or jail, on Akrestsin Street is 110 people, but massive overcrowding occurred when hundreds of demonstrators were rounded up on one day, as happened numerous times during the regular Sunday protests since August.

“I’ve never heard people screaming in pain like that,” 47-year-old Vladimir said. “Police beat those who looked different and those who cried for their mothers the loudest.” Vladimir himself did not even participate in the protests; he just went out to the store near his house in the evening. He was wearing slippers, shorts, and a T-shirt, and there was a protest two blocks away. The siloviki (security forces) “cleared” the streets: they took absolutely everyone they found there. Vladimir was not lucky that night.

What is Akrestsin?

The complex on Akrestsin Street comprises a temporary detention center and a jail. Most often the two institutions are lumped together in speech into one capacious concept of “Akrestsin”.

In general, suspects are housed in the detention center before trial and transferred to the isolation center to serve their sentence. The conditions of detention in the two buildings are slightly different. For example, prisoners must wear special slippers in the detention center cells. This seemingly small detail can be significant, as when the weather grew cold this fall before the heating in the building was turned on.

“I wrapped my feet with a newspaper and put on socks on top. It was a little warmer that way,” said Evgenia, 28. She spent three mid-October days in detention. She and her cellmate were not given bed linen or even mattresses. They had just one blanket and slept in an embrace to keep warm.

“I fainted, but they never called an ambulance. They said I was faking,” Evgenia said. When they released her, her hoodie was covered in blood, because she had suffered nosebleeds every morning.

The beds are different too. In the detention center, the mattress rests on a flat piece of wood, while beds in the jail have metal mesh with large holes, and they can be painful to lie on even if there is a mattress. Basketball player Elena Levchenko, who spent 15 days in the jail, said all the mattresses were removed from her cell and the women slept on the bare mesh. Some put sanitary pads on their thighs to ease the pressure, or glued pads at the foot of the bed to protect their feet. The hot water was not working in her cell, and the toilet would not flush.

Prisoners also complained of insects in the cells and of food being served on dirty dishes. The inmates have no contact with the outside world, even through a window, since the glass has been replaced by opaque material. Lights burn 24 hours a day in the cells, bright ones from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. and at night a single lamp over the door, known as “the moon.”

“Nobody Asked to Go to the Toilet”

Akrestsin’s bad reputation is nothing new, but not until this year did it become synonymous with cruelty on a massive scale.

In December 2010, after Lukashenka’s re-election, more than 600 people were detained in Minsk. Those who admitted guilt were jailed for 10 days, those who did not got 15 days. Rather than resort to mass beatings and abuse, the system then derided detainees in other ways. After release, many were not allowed to walk out to freedom but were driven in police vans to remote parts of the city. Frightened, cold, hungry, with dead phones and often without money, they had to find ways to get home.

The methods used this year make the old bullying look like a small prank. In 2020, people in the detention center and the jail have had their bones broken, their hair pulled out, and their internal organs damaged.

Since August, a group of journalists and volunteers together with Belarusian and international human rights advocates has collected and published accounts of torture and inhumane treatment at the hands of police and prison authorities. Here are some of the testimonies documented by the August 2020 project:

Not one of the detainees escaped a beating. Someone’s leg was broken, another person’s arm. They shouted at one guy to put his hand behind his back, and he said he couldn’t move it as his shoulder was dislocated. They beat him even more. Nobody asked to go to the toilet, whoever needed to, urinated right there.

– Pavel, 31

When we asked for water or to call a doctor they answered: “Die, bitches,” “Scum, I don’t sleep for three days either,” “You bitches, animals.” In the best case it was a simple “Wait.

– Tamara, 35

They dragged people out to the yard. They forced them to their knees. If someone would not kneel, they began to beat their legs and knees, hit them below the kneecap with a baton. My right leg was already injured, and it bent badly. More than a month has passed since then, and it still has a blue bruise.

– Oleg, 52

They brought 33 more girls to our four-bed cell, where there had been 20 people already. We couldn’t breathe. We asked them to at least open a “birdfeeder” [a small window used to dispense food to detainees], to which the “famous” woman [the riot police officer] replied. “You won’t die!”

– Marina, 32

The methods of abuse varied. Some detainees said they were marked with paint even before they got to Akrestsin and were singled out for even more brutal treatment. As a general rule, those who were considered the organizers of the demonstrations or who stood out from the crowd because of dreadlocks, piercings, brightly colored hair, etc. were the most bullied.

“There was no logic in how they decided who was an organizer,” recalled Yulia, whom we heard from above. “No logic at all. It’s just that some people tortured other people and enjoyed it. I heard someone saying they should give him someone to beat because he hadn’t beaten anyone yet that day.”

Sometimes ambulances were summoned to Akrestsin, but the doctors often couldn’t do their jobs there and were not allowed to hospitalize everyone who needed it. “People in uniform could burst into an ambulance and order one of the victims to return to the cell. In response to our indignation, they also threatened us with violence,” said one nurse, who requested anonymity to protect herself.

Waves of Violence

Conditions at Akrestsin became quite bearable in September, without explanation. Hardly anyone was beaten, the cells were not overcrowded, the guards did not even stop people from sitting or lying on their beds during the day. Detainees could receive packages with necessities from relatives on any working day, and sometimes even their friends could deliver packages.

“It was practically a sanatorium. There was always a lot of food in the cell, and during the day we usually slept at least a couple of hours,” 24-year-old Lisa – held for nine days in September – recalled.

Then, in late October, Lukashenka replaced his interior minister. Yuri Karaev departed, replaced by Ivan Kubrakov. To judge by the accounts of people sentenced to administrative jail terms, conditions then began to deteriorate. Journalists and social media began relaying more and more complaints of torture and other abuses such as depriving inmates of hot water and mattresses, and the cells again were filled to overflowing.

“I used to believe guards too could be normal people. But now I see that everything depends only on what orders they are given. If the bosses will give the order to kill all arrested people, they will kill them, then go home, have dinner with their families and sleep peacefully all night long,” 40-year-old Ilya said. He believes in God and is confident that good will win out in the end. “But God’s retribution is no longer enough for me. I want these people to take responsibility for everything during their lifetime. You cannot rely on God and let them continue to do evil things.”

It is difficult to understand what exactly determines the level of violence in isolation and detention centers, and why conditions can vary so much. Some cells are overcrowded, others not, some have hot water while the cell next door doesn’t. Prisoners ask why one paramedic ignores all complaints and requests, while another calmly brings toothbrushes and toothpaste when she finds out that people need them.

“The main thing is not to trust them and not to hope they will keep their promises. The conditions of detention can change at any time, and you just have to accept it,” Ilya said. “And they don’t always change for the worse. Today’s shift screams and threatens, and tomorrow’s shift can bring bottles of drinking water so that we don’t drink from the tap. This can also happen.”

Volunteer Camp

Several thousand people were detained in Minsk in the first days after the presidential election. Relatives of the detainees waited outside the Akrestsin detention center trying to find out if their relatives were there or simply hoping for some news about the detainees. This situation could have descended into confusion if not for the volunteers – caring people who quickly organized a camp in the nearby park.

Initially, the help consisted of calming down those who were waiting for word on relatives, handing out food and drinks, and giving people blankets for the night. Doctors were also on duty in the camp, examining those released from the center and giving first aid when necessary. Over time, a whole mini-city took shape: in the camp, you could talk with lawyers and psychologists, correctly pack the necessities bags for detainees, pick up details about the conditions of detention. Volunteers fed and watered people who were released, provided free transport to get them home, and provided moral support to everyone who needed it.

“When my son was detained, I had no idea what to do, and I definitely would not have coped with all this without the volunteers. I didn’t even know exactly where he was! I came to Akrestsin simply because I had to do something at least. But in the camp, they calmed me down, found my son on the lists, explained to me what to put in the bag. Such help and solidarity are worth a lot,”, said 58-year-old Lyudmila, whose son spent 10 days in Akrestsin.

The camp operated 24 hours a day and seven days a week for almost two months. The volunteers advocated nonaggressive cooperation with the staff at Akrestsin, and this led to conflicts with more radical protesters and some relatives of the detainees. “Once a woman, out of frustration, began to bang on the entrance doors and a couple of minutes later, we were told no more bags would be accepted that day. To be able to help people, we had to follow certain rules. It was difficult to explain that to angry relatives,” a volunteer who asked not to be named recalled.

On 4 October a column of protesters marched to Akrestsin Street to demand the release of all those arrested for political reasons. Five hundred meters from the complex, they were met by people who introduced themselves as volunteers and asked that the column turn around. Later these people claimed they hadn’t been in the camp when protesters arrived.

So the camp stopped its work, and the center began accepting bags on Thursdays only. The stated reason is the coronavirus pandemic. This has been the standard approach for months; the pandemic is often used to justify repression and violations of the law. The pandemic was cited as the reason independent observers were not allowed to observe the presidential election and foreign journalists were denied accreditation. Yet, some detainees said they were ignored or denied adequate treatment when they began to show symptoms of COVID-19 while in detention.

The danger of infection has also been the justification for preventing certain detainees from receiving bags from their relatives. Another ploy is to manipulate the timing of prisoner transfers to prevent their receiving anything from outside. On Wednesdays, detainees are transferred to detention centers in the cities of Zhodino and Baranovichi. Bags for detainees in Baranovichi, however, are accepted on Tuesdays, and on Wednesdays at Zhodino, preventing their receiving bags for the next week. As a result, detainees may spend days without warm clothes, a change of underwear, or hygiene products and cannot even get the medicines they need.

Official Position

The authorities deny that torture and ill-treatment of arrested people have been and continue to be used in detention centers. Many people who filed official allegations of torture have been prosecuted for participation or organization of riots.

When star basketball player Yelena Levchenko said she spent 13 days in Akrestsin Street sleeping on metal slats with no bed linen, the authorities accused her of exaggerating. Other complaints of abuse typically go unanswered.

To date, not a single criminal case has been opened in Belarus against those accused of beatings and torture of detainees.