Prague startup employs homeless people as tour guides and wants to change society

Despite being often regarded as poverty tourism, the social enterprise Pragulic employs homeless people to show the Czech capital through their eyes – and gets them needed help.

He emerges from a rear entrance of Praha-Smíchov, a railway station located well outside the city centre. By most measures, he is nondescript: a middle-age man in dark trousers and a fleece sweatshirt with a pin button fastened to it. “I am on the right track,” the button reads. In the next four hours, this man with a wide, rakish smile and a soft voice will give me a rather unconventional tour of Prague, showing a hidden side of the city, the one that is far away from any usual sightseeing affairs.

His name is Robert Pochop. He works for Pragulic, a Czech social enterprise that offers alternative tours given by homeless guides. It was launched in 2012 by three fellow students after they were awarded a €1,500 social entrepreneurship grant.

Tereza Jurečková, co-founder, tells me that in the beginning, their aim was clear: to provide employment to homeless people, or those in precarious social situations. Now the mission is broader: they want to tackle stereotypes and increase empathy for the homeless. Education is a way to achieve a bigger change, Jurečková believes.

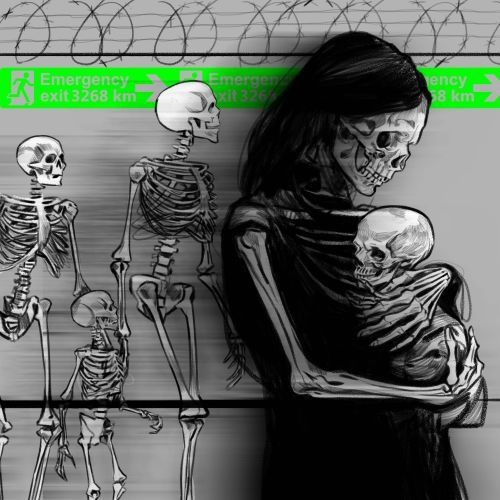

Similar homeless tours exist in major European cities, such as Barcelona, Amsterdam, Athens, Vienna. In London, Unseen Tours specifically weaves the life experiences of its homeless guides into trips to big-ticket attractions and neighbourhoods like Soho and Covent Garden. In Berlin, apart from homeless guides, there are also refugees and migrants, who share their personal experience of moving to a new city.

These homeless tours raise many of the same questions that excursions into the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the townships of Johannesburg or the garbage dumps of Mexico do. Where’s the line between voyeurism and understanding? What about the exploitative aspect of such poverty tourism? Does it really help?

Robert, my Pragulic guide, is addressing those questions as we are taking a walk in a forest park called Cibulka. We communicate in both English and Russian, and he switches back and forth between the two languages. He mentions that he also speaks Italian in addition to his native Czech.

Robert became homeless 15 years ago after his grandfather’s house was sold. Prior to that, he used to work in construction and as a warehouse worker at Amazon. But as he turned 52, he says he can’t easily find a well-paid job. Tours with Pragulic is Robert’s only source of income. What he currently earns is not enough to rent an apartment. That is why he currently sleeps on a sofa in his brother’s flat. But his work as a guide is more than just money, he says. “I feel valued and appreciated. When I can talk to people, share my story, it is the best medicine I can get.”

In order to design his tour, he visited a local library to get more information about the park, which is considered to be one of the few surviving examples of Prague’s late Baroque epoch. Besides, Cibulka is where Robert often sleeps in summers.

From homelessness to stable accommodation

Přemysl Kramerius from the Salvation Army, an international charity organisation with its branch in Prague, is giving an outlined list of the many reasons of homelessness.

“This can be alcohol, drugs, divorce, unemployment, abuse, bullying at school, the lack of family support,” he says. “But there’s no one specific cause. It’s often a series of events in someone’s life that leads to homelessness.”

For Petr, it was heroin and methamphetamine. We meet at his small office, where he works as a receptionist for Pragulic, which is another work opportunity that the social enterprise provides. He is 50, but says Pragulic is his first legal employment.

It’s not like Petr never worked. As a teenager of the late communist era, he used to sell everything from jeans and electronics to foreign currency. Then he started selling drugs and became a drug addict himself. Around three years ago, when he lost his leg due to infection, he started a drug replacement therapy. It is also when his therapist told him about Pragulic, and he decided to give it a try. It took at least a year to design a tour – Petr is also a guide despite having one leg – until he started working.

“I had many hard moments, breakdowns, when I could disappear for days because of my addiction. Pragulic would wait till I am clean, and we would start it over again,” he says and looks at me. “Do you know any other employer who would have this much patience?” he asks.

After each tour, guides receive tips from tourists and earn a fixed amount of 350 Czech Republic koruna (€13) from Pragulic. For as little as it seems, Jurečková explains, Pragulic also helps with accommodation: pays deposit or several months in advance, sometimes without expecting the money back. This deposit is crucial for someone sleeping rough: the lack of this money often prevents a homeless person from getting accommodation. Pragulic also offers legal advice, psychological counselling or free haircuts.

“We offer something like employee’s benefits,” Jurečková adds. “If they need a mobile phone and a laptop, we provide both. Besides, we teach them computer, communication and presentation skills. And often all the basic living skills, such as how to deal with money or take care of themselves.”

Now that the enterprise has become well-known, local businesses joined. One food chain store provides vouchers to guides, which they can use to get a free meal. Pragulic collaborates with schools and other organisations abroad, where its team give presentations about homelessness and how to run a social enterprise. It provides a public wardrobe where people can donate their clothes. In another example, the city authorities hired Pragulic employees to pick up trash on streets.

As well as walking tours, Pragulic offers a team-building experience that is mainly aimed at managers and employees of corporations, and a homeless challenge that involves spending 24 hours with one of its guides surviving on the streets.

How we define homelessness

There are among 23,900 homeless people living in the Czech Republic, according to last year’s government’s report. At first glance, the country is doing well, when compared to neighbouring Germany and Slovakia where the percentage of homeless is higher.

“It depends how we define homelessness,” says Martin Šimáček, director of the Institute for Social Inclusion, a think tank that focuses on social policies towards socially excluded localities, poverty and discrimination. Between 2009 and 2015, he was employed as director of the Agency for Social Inclusion at the Czech government, a state body established to combat social exclusion.

There are various definitions of homelessness, depending on a country and social conditions. But apart from rough-sleeping, which is the most common one, some definitions focus on the absence of a certain minimum quality of housing and a loss of a sense of social belonging. Šimáček estimates that there are more than 30,000 people living in the so-called dormitories in the Czech Republic, which is essentially cheap and often overcrowded accommodation. They might have a roof above their heads, but their living conditions are less than adequate, which is “a sort of homelessness,” Šimáček says. If we include unhygienic temporary accommodation, it will double the government’s figure on homelessness.

Non-governmental organisations and charities are the main social support providers for vulnerable people in the Czech Republic. Gabriela Sčotková from the charity Naděje (Hope) that provides shelters and other services to the homeless, elderly and people with disabilities, explains in an email that there is an urgent need for national social housing law. Without it, there is no legal regulation supporting the social housing sector. Housing policies are locally designated at municipal level with minimal input from regional authorities.

“Collaboration with the local authorities is challenging,” she writes. Naděje has to deal with representatives of every single district of Prague where the charity provides social services. “Some are doing more, some less,” she writes. Also, since there are municipal and regional elections every four years in the Czech Republic, she explains further, every four years her organisation has to start all over again with a newly elected government.

The unemployment rate currently holds at record low. In most regions across the Czech Republic, it’s not difficult to find work. The problem is that many people can’t make a living from that work. At present, there are 863,000 Czechs – out of a population of 10.6 million – affected by debt collection. They may ultimately lose their homes as well. Even small debts like unpaid fines or utility bills can grow into sums many can never repay.

A more targeted help

As a result of their indebtedness, people turn to the shadow economy. It happened to one of the former Pragulic guides, who currently works off the books in construction to evade aggressive debt collectors. Jurečková explains that as long as his debts are not eased, he will not be able to move on, work officially and earn decent money to support his family.

Pragulic currently employs nine people. Some of them joined in the past few years like Petr. Others have been working for a longer time, such as Karim who’s been with Pragulic from the very beginning. A former sex worker and drug user, he now appears on local TV talking about his experience of being homeless.

Jurečková is trying to be cautious though. “We enjoy hearing success stories of former homeless people who got back on their feet,” she tells me. “Although it now looks stable and our guides are doing a great job, I want to emphasise that any person can easily drop out at any moment,” she says. They are at risk of becoming homeless again, either because of addictions, debts or any other reason.

In one case, a person suffered from severe depression and eventually dropped out, despite receiving psychological help. In another case, Jurečková and her team have to seek a living place for a guide every time he is kicked out from rented accommodation. “He doesn’t really know how to take care of himself and his apartment. But he works hard and educates thousands and thousands of people about homelessness,” she explains.

Initially guides were recruited via the DivaDno theatre that worked with the homeless. Now these are usually social services that recommend a prospective employee, or Pragulic finds them directly on the street. The latter happened to Ivana, who’s been homeless since her teenage years, having grown up in an abusive family. She was rough sleeping outside Prague’s main railway station when Jurečková found her. Ivana now works as a guide and has stable accommodation.

Pragulic establishes a long-lasting, meaningful relationship with its guides and forms a sort of community. Those who have been employed for a longer period help new workers to get their papers sorted. The social business is sustainable and raises profits, which are reinvested into the support services. Pragulic has opened its branch in Ostrava and has ambitions to expand into other cities in the Czech Republic.

What it wasn’t able to track yet is that broader mission of increasing the social awareness about homelessness and empathy mentioned in the beginning of this story. With more than 70,000 customers to date, Pragulic plans to measure its impact. In the next few months, it wants to implement metrics that it created with the help of global social enterprise enabler Ashoka. It will essentially be a feedback form for customers to check how and whether their attitudes towards the homeless changed before and after each tour.