The house collapsed and sank in a pond in Mysłowice-Wesoła because of the mining plant and its activity. “I don’t want the same to happen to mine house,” says Alicja Zdziechiewicz, who lives in a nearby Imielin, where the Ziemowit mine wants to mine coal. The inhabitants of Mysłowice protest against the decision of the ECI company to build a mining plant there and the expansion of the Sobieski mining plant planned by Tauron. The city of Rybnik does not want the mine either. And the neighbours living near the Polesie National Park are afraid of both the expansion of the Bogdanka mine and plans of a new mining plant signalled by the Australians. However, in Nowa Ruda in Lower Silesia, the new mine would be more than welcome. The problem is that the plans to build new mining plants are mainly theoretical, and it has not changed for years, as opposed to the expansion of the existing ones.

The Polish government announced phasing out hard coal as an energy source by 2049. The latest mining plant which started running in Poland was the Budryk mine in Ornontowice in the 1990s. Today, a new coal mine is built by Jastrzębska Spółka Węglowa. However, only coking coal needed for steel production will be extracted there (by the way, such a mine is also planned in the “carbon neutral” UK). Coking coal is on the EU’s list of strategic raw materials, while steam coal is in retreat.

In Poland, there are plans to build private hard coal mines – both steam and coking coal mines-and plans to expand existing hard coal mines. At least in theory. And what do the potential neighbours of all these investments think? We visited Upper and Lower Silesia and the Lublin region – where the new mines are planned to be built and where the expansion of the existing ones is planned. We talked with residents and local government officials; we saw the places of potential investments and their neighbourhoods. We also examined the potential disadvantages and advantages of new mines.

Mysłowice

Kosztowy district. ECI, a developer from Warsaw, wants to build the Brzezinka mine here. Sobieski mine, which belongs to Tauron Polska Energia SA and now operates in Jaworzno, also expands its infrastructure. Posters are hanging on many houses with a firm “no” to constructing the new mine. There is also a Facebook group gathering people who are against the mining plant.

In November 2020, the Ministry of Climate and Environment issued a license for Brzezinka copartnership to extract hard coal from the Brzezinka 3 deposit in Mysłowice. “It is another crucial step on the way to the exploitation of this deposit. We are in the middle of the road because the development of a mining plant is a complex process – says Piotr Talarek, the management board advisor of Brzezinka copartnership. – According to the schedule, the design work and construction of the Brzezinka 3 mining plant will be carried out for no more than nine years, and the coal extraction will start no later than in 2029. We estimate that the plant will produce up to 3 million tons of coal annually,” he adds.

The inhabitants of Mysłowice realize what the mining plant nearby their city means. The place is defaced by the ruins of the closed Mysłowice mine, Wesoła mine is still working, and mining damage can be easily found, whether it is a cracked building or a bumpy road.

“No one has talked about the new mining plant in Mysłowice. Plots were sold to developers, and it turns out that there were also talks with the investor,” explains Andrzej Szłapa, who built a house in the vicinity of a potential mine. “Yes, there are deposits of coal here, but even the former Katowicki Holding Węglowy – now a part of Polska Grupa Górnicza – and the owner of the Mysłowice-Wesoła mine, has given up on its mining plans here”, he says.

“The hydrogeological situation in this area is dramatic, so Katowicki Holding Węglowy, taking it under consideration, withdrew from the project,” explains another Mysłowice resident, Piotr Oślizło, a construction expert. “Before World War I, shallow exploitation was carried out in this area, there were voids that no one filled, so if someone starts mining on 700-1000 m, the water will start to migrate,” he explains. The voids from exploitation are filled with a mixture of water and sand. It protects the ground surface from subsidence more than the process of controlled collapsing, which means filling voids with rocks underground.

Therefore extraction in this area means risking soil leaching, land subsidence and property collapse.

In the Wesoła district, everyone knows the house that has collapsed and is stuck today in a large pond where you can fish. As a result of the Mysłowice-Wesoła mine exploitation, land subsidence and surface water appeared there. That is how the pond was created, and the building collapsed.

The urban development plan was about to be changed, but nothing was done about it. A few years ago, over 600 residents signed a petition objecting the coal mine project,” says Gabriela Saternus, a councillor of the Kosztowy district in Mysłowice. That part of the city is a Silesian “Bermuda Triangle”. It is not only about the Brzezinka 3 mine, but also about the Brzezinka 1 field – i.e. the expansion of the Sobieski coal mine in Jaworzno belonging to Tauron Wydobycie S.A. (the company did not reply to our questions) and the effects of the expansion of the Piast-Ziemowit coal mine of Polska Grupa Górnicza. It will first affect the neighbouring Imielin and then Mysłowice.

“In the design, Tauron did not consider the water main, although it has existed for over 30 years. They were given maps with no waterworks,” explains Małgorzata Manowska, a geologist from the Faculty of Earth Sciences at the University of Silesia. According to her, the exploitation of Brzezinka 1 (Tauron) and Brzezinka 3 (ECI) will lead to the collapsing of surrounding houses because neither of them has foundations protecting against underground exploitation. The nearby highway may also be damaged.

“Since 2012, the authorities of Mysłowice have been negotiating the construction of the coal mine. For me, the city must develop economically, and the launch of a modern coal mine will certainly contribute to this. Moreover, about 25 million zlotys will annually boost the city’s budget from all kinds of local fees. When it comes to the disadvantages, well, it is the residents’ fear of mining damage, and I understand it,” says Dariusz Wójtowicz, the mayor of Mysłowice. “Today, however, the greater threat to Mysłowice is the already existing plants. They extract the coal using the method, which causes great degradation of the natural environment. The new regulations do not allow that extraction method anymore, and I will do my best to keep the residents safe. We are planning to hold a referendum, and right now, this problem is being dealt with by our lawyers,” he admits.

“What’s my opinion on the president of Mysłowice’s idea to organize a referendum on the construction of the mine? Frankly speaking, we were stunned. We analyze that rather general declaration, and we will convey our formal stance. In recent weeks, we have been observing statements from a small group of Mysłowice residents who express their concerns. In our opinion, these fears are unfounded because the mining plant will be almost impalpable to the environment and the buildings on the surface,” argues Piotr Talarek. “The company’s representatives have engaged in the dialogue with the inhabitants of Mysłowice practically since 2012, as part of the so-called voluntary consultations. We wanted to establish a completely new standard of agreements based on transparency and openness, to present the investment and to discuss it.” Residents admit that the consultations took place, but they add their arguments were not taken into account. “Well, there were a lot of questions at the meetings, but the company’s representatives explained that they were unable to answer them in detail,” explains Manowska.

Imielin

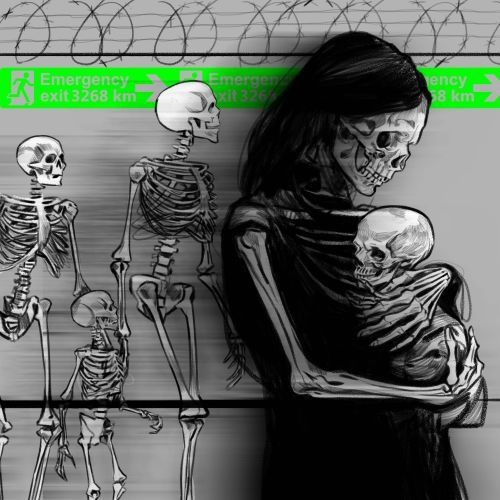

“We are just afraid our homes will collapse,” says Alicja Zdziechiewicz, who lives in Imielin near Mysłowice. She is a teacher and an activist of the Zielony Imielin association, which has been protesting against the expansion of the Piast-Ziemowit mine of Polska Grupa Górnicza for years. The residents here can breathe a sigh of relief, at least for now, because the General Directorate for Environmental Protection has repealed the lower court’s decision, which was favourable to PGG’s plans. Will the company fight for new coal deposits? Especially in plans to close Polish steam coal mines by 2049, currently negotiated by the government with the trade unions? It is not known.

Polska Grupa Górnicza did not respond to Outriders’ questions regarding the expansion of the mine. Considering the agreement between the government and miners on the closure of mines, negotiated on April 22 2021 – after long six months of talks – returning to the plan of expanding the mine with the Imielin deposit seems unlikely.

“When we built our houses, we were assured that there would be no mining operation in the area, so we did not need to apply the same security features as real estate built on mining areas. We built houses, but the mining plans have changed,” explains Zdziechiewicz. And that’s not all when it comes to mining damage.

“Mining activity in Imielin could damage the underground drinking water reservoir,” says Anna Meres from Greenpeace Polska. “During exploitation, the so-called cone of depression is created, and within a radius of several kilometres, groundwater disappears, and the soil is drained. In addition, empty corridors underground collapse, and the ground surface settles. Basins are a catchment area for surface waters, so huge areas are flooded. The water pumped out of the mine containing heavy metals ends up in the rivers and poses a threat to aquatic ecosystems.

Tomasz Wrona from the Nasza Ziemia association confirms that mining damage related to the potential expansion of the Imielin coal mine will also affect the aforementioned Kosztowy district in Mysłowice. “The Kosztowy district is a direct neighbour of Imielin with a forest between them. The Imielin-Północ coalfield, which is to be built, ends in the centre of our district,” he explains.

Plans to build a Paruszowiec private mine in Rybnik, about 60 km from Mysłowice, also seem unrealistic. The Bapro company from Dąbrowa Górnicza wanted to exploit the deposits there. In January, a court in Gliwice blocked the investor’s plans favouring an urban development plan that does not allow the coal mine to be built. It suited city authorities and residents, who were against the investments. According to the rybnik.com.pl, the Silesian voivode asked for an annulment of the sentence, and the case will go to trial again.

The plans for exploiting the Orzesze deposit by Silesian Coal, a company belonging to the German group HMS Bergbau, have also been known for years. For that purpose, Silesian Coal wanted to use the infrastructure of the Krupiński mine, but it was closed in 2017. The British investor Tama Resources intended to buy and reactivate it, but it failed.

Lower Silesia

However, not everywhere the potential neighbours of the mines are against new mining plants. In Nowa Ruda in Lower Silesia, people long for coal mines. And there have been none of them for over 20 years there. Therefore, the municipality residents joyfully welcomed the Australian Balamara Resources Limited company. The Australians announced the new coking coal mine construction in the areas of formerly existing mines.

Yet, for three years, a private investor has not received an explicit declaration from the state authorities about whether it can try its chances or not – the license application was submitted in the second half of 2018. Outriders unofficially determined that the Australians are considering legal proceedings and a complaint about administrative inactivity. Everybody remembers that Nowa Ruda was famous for coal back in the days.

Both the coal mine and the power plant were operating in the nearby Ludwikowice Kłodzkie. Today, only the devastated ruins of both plants remain. Residents recall the times of a mining splendour. “The mining was in full swing; everyone was working,” some people living in Ludwikowice say while sipping beer, more interested in our drone than in the conversation about the coal mines. One of them tried to catch the drone; the other recalled how quickly and without a plan the surrounding mining plants were closed.

In nearby Wałbrzych, hardly anyone believes in plans to build new mines. Retired miners believe that no one will get a concession for coal extraction here because there are also deposits of copper ore in this region, “being kept for KGHM”. For the time being, Polska Miedź mines in another part of the region: in the Lubin, Rudna and Polkowice-Sieroszowice mines. “After all, copper is a much more desirable and future-oriented material, so it is hard to believe someone gets a license to exploit coal if you can make better money on something else,” that’s what we can hear in Wałbrzych. The people here are more focused on history and maintaining tradition. The extension of the Old Mine exhibition, a museum facility that has been operating for several years, is about to cost 30 mln zlotys. Part of the building will be preserved as a ruined building, and another – apart from the underground route available today (in non-lockdown times) – will be open to tourists. It is a former coal processing plant. The Old Mine looks to funds from the Just Transition funding sources – EU funds for post-mining regions. Poland may get several billion zlotys.

Lublin region

We are in Wojciechów, where runs the border of the Poleski National Park buffer zone. Maciej Mroczek, a beef cattle breeder, has over a hundred cows here. His neighbours breed dairy cows. Maciej and his wife settled here 20 years ago – it is far from the Bogdanka mine in Lublin and not far from the Poleski National Park, existing since 1990. They thought, since it was a place without an asphalt road, no one would think about investments. Today it turns out that they were wrong. “When Balamara started drilling for the Karolina mine, we knew that something was wrong because these deposits were documented in the 1980s. But I thought that since there is a marl here (relatively plastic, soft sedimentary rock – editor’s note) .), nobody will seriously think about mining coal. Later it turned out that one of the main sidewalks would run sort of through the centre of my yard,” says Mroczek.

Andrzej Zibrow, the Polish representative of Balamara company (the same that wants to build the mine in Nowa Ruda), admits that in November 2020, Polish authorities approved the geological documentation of the Karolina mine in the Sawin 1 field in Polesie. The company has the exclusivity for three years in over 130 square kilometres plus the confirmation of coking coal deposit in the documentation needed for steel production.

Outriders checked that on April 15 and 16, 2021, Balamara’s authorities held a teleconference with Polesian local government officials on constructing a new mining plant. “The investor has submitted an application to adjust the study and spatial development plan for mining areas, and it is being analyzed,” admits Zbigniew Raźniewski, deputy mayor of the Sawin municipality, talking to Outriders. He notices, however, that it is not known when decisions will be made, and it is difficult to talk about details. He adds that the new investment is an opportunity for development for the commune. And it’s not just about jobs. “We have large investment needs, basic ones. We have waterworks in only three villages out of 19, the sewage system is only in Sawin, and we still have many gravel roads,” he enumerates.

“At the same time, it is still unclear whether the mine would be built. Is it going to be Sawin or Hańsk municipality,” says Anna Meres from Greenpeace Polska.

“Tourism will end, and it’s just started to develop here. Who will come to that usually quiet and peaceful Polesie, or buy plots of land here if the trains and trucks full of coal go back and forth in the area?” – asks Elżbieta Krassowska, who runs an agritourism business in Pieszowola in the Sosnowica municipality.

Balamara’s project is not the only problem for Polesie residents. And it is not even because – as it seems – the plans of Prairie Mining, another Australian company, are gone. It wanted to build the Jan Karski Mine in the Lublin region and reactivate Dębieńsko in Silesia (and then intended to sell it to Jastrzębska Spółka Węglowa). When the plans failed, the company sued the Polish state for 10 billion zlotys in international arbitration; the case is still open). The problem is that the Bogdanka mine also wants to develop. It should be closed in 2049 because of phasing out coal production, but if it starts to mine coking coal, it has a chance to operate longer.

“According to our strategy, we want to use coking coal deposits, which is to be mined from 2026,” admits Artur Wasil, the president of Lubelski Węgiel Bogdanka. He reassures, however, that the mine will bypass the Poleski National Park. “We do not have a license to operate near the park. The local community recognizes our efforts to minimize the effects of mining activities that have been undertaken for years. We try to be a good neighbour,” he adds.

Plans for the construction or expansion of mines in the Lublin region are a problem for people and unique flora and fauna.

“The most serious threat posed by mining plans is a change of water conditions in the environment. It can be said with high probability that as a result of the construction of the Karolina mine, the peatlands of Bagno Bubnów and Bagno Staw, located in the Polesie National Park, will either dry out or be flooded. In both cases, they will turn from a carbon store, which permanently binds carbon dioxide, into a source of greenhouse gases. The dried peat oxidizes to carbon dioxide, and the flooded peatland emits methane, a much stronger greenhouse gas. It is worth noting that carbon dioxide emissions from drained peatlands are as much as 10 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions in Poland. Healthy peatlands store water better than any artificial reservoir; they prevent flooding and reduce the effects of drought. Arguments about the harmful mines that convince the inhabitants in Silesia will not necessarily work in the case of Polesie. It is a sparsely populated area, so few will feel the effects of subsidence, which is an unavoidable consequence of coal mining. Unfortunately, the argument about the need to protect biodiversity is probably inefficient, and nature is the most valuable one here, says Piotr Chibowski, PhD student at the Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw. “Few probably know what an aquatic warbler is. It is a rare, endangered species of migratory bird, and 4% of its world population lives in Bagno Bubnów and Bagno Staw. It is just one of many pieces of evidence that this area is truly unique in terms of nature. Wetlands, including peatlands, are the most intensively damaged ecosystems in the world. It is a big test for the nature protection system in Poland because the most important national and international forms of its protection are under threat. The irreversible destruction of parts of the Poleski National Park could be a reason for its official decrease. And the European Union will rightly charge us for insufficient protection of Natura 2000 sites,” he adds.

“We coexist with the Bogdanka mine because it was built before us; we also have fewer concerns about its plans, although the effects of its exploitation may also be harmful to us,” says Jarosław Szymański, the head of the Poleski National Park. We meet in Urszulin, at the National Park management headquarters. He also talks to us about the endangered aquatic warbler, about the famous European pond turtles and cranes, which have found their breeding sites in Polesie. “You know, theoretically, we are moving away from coal,” he adds, summing up our conversation.