Lukashenko may be announced the winner. But his victory won’t last long

The outcome won’t be any different. But the people of Belarus have already shown they want change.

In the past weeks and months, Belarus has seen some of the most unusual scenes in its history.

Kilometres-long lines of people waiting to leave signatures in support of their candidates. Thousands gathered in provincial towns, where protests never happened before. It culminated in a massive rally in Minsk that drew a crowd of more than 60,000, the largest since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The people of Belarus chant, sing and shout one word: “Change!”

But President Aleksandr Lukashenko, who has ruled since 1994, has a different plan.

“We will not give this country to anyone,” he promised early June.

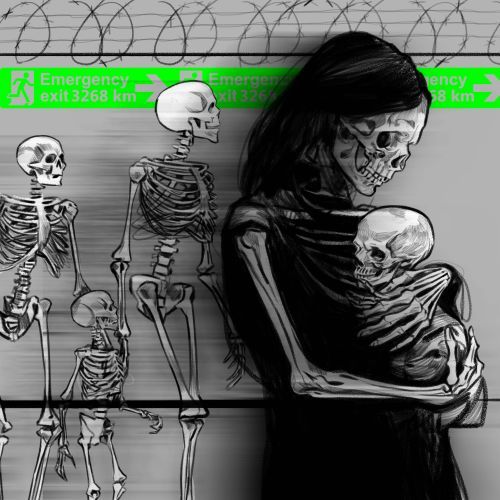

And he keeps fulfilling this promise. In the past weeks and months, Belarus has also seen some of the most outrageous and yet familiar scenes. Plainclothes police officers choking unarmed men. A female cyclist who has her hand broken as a result of a brutal detention. Journalists beaten and arrested while reporting on air. Independent observers expelled from polling stations and detained.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

At a polling station in Partyzanski district in Minsk, Maria Nesterova, an independent observer, has to monitor the turnout from behind the fence, as she is not allowed in a school building where the voting takes place. She said that one of the observers at the same polling station was detained yesterday and is currently being held at a detention centre. More than 50 observers were detained across the country.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, a reluctant candidate who was pushed into politics after her blogger husband Siarhei was arrested in May, already voted herself. Hundreds of people greeted her at a polling station in Minsk. They chanted, “Sveta! Sveta!”

In Belarus, a former English teacher and a housewife, became the face of an otherwise faceless protest. Tsikhanouskaya’s challenge is being supported by the two “fighting girlfriends” – Veranika Tsepkalo, the wife of former presidential hopeful Valery Tsepkalo, and Maryia Kalesnikava, a representative of the imprisoned hopeful Viktar Babaryka.

Tsikhanouskaya had to leave her home fearing prosecution, and previously sent her children abroad. Veranika Tsepkalo fled Belarus. Maryia Kalesnikava was briefly detained, though soon released.

Lukashenko is seeking a sixth term in office with the same autocratic methods he has used in the past. But the reality has already changed.

An unlikely challenger

As much as Lukashenko tries to show that these are “unhappy women” who are steered by someone else, the trio has amassed largest opposition election rallies across Belarus.

“Why can’t we decide for ourselves what our city should be like and what our country should be like?” Tsikhanouskaya addressed the crowd of an estimated 20,000 in Brest on 2 August.

“We were patient. We were silent. We were scared. But we are not scared anymore!” she said. The crowd chanted, “Well done!”

She tells the people of Belarus that she loves them. And they seem to love her back. In Brest, they waited for hours, despite the hot weather. In Vaukavysk, they stood in the pouring rain. In Baranavichy, Tsikhanouskaya was greeted with bread and salt, a popular welcome ceremony in Belarus. In Grodno, someone brought an icon as a gift. People take selfies with the trio, bring self-made portraits of the trio, and put children in their arms. Wherever the women appear, Belarusians greet them as their heroes.

In a neat irony, the last time when Belarusians showed their admiration to an opposition politician was in 1994, when a young and energetic candidate emerged. His name was Aleksandr Lukashenko.

These days, crowds are chanting the name of an unexperienced and accidental candidate, who – similarly to Lukashenko in 1994 – has become a rising political star. Despite the incumbent’s claims that Belarus is not “mature enough” for a female leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya has become his main political rival.

“Belarusians are waking up. They are ready to speak out,” told me Emilia Haurus, a teacher at the Belarusian language course in Hrodna, a city in western Belarus.

She is not naive, though. “Brutal repressions will follow. Yet I have a small hope that the situation will eventually change. There’s a joke that when Lukashenko is gone, Belarusians will drink all the champagne in the country,” she said.

“Tsikhanouskaya is my candidate, and I will vote for her,” told me Vladimir, an army paratrooper from Brest, who did not give his last name. On the day of Tsikhanouskaya’s rally in Brest, he celebrated Airborne Forces Day, a professional military holiday of airborne troops. I saw at least a dozen of paratroopers who came to the rally, wearing military insignia and waving their flags.

Vladimir said that he is tired of hearing “constant lies” from the authorities and on state television. “26 years is enough, and we need someone new,” he said, referring to Lukashenko’s more than a quarter-century rule.

“Before this summer, I was apolitical. Now I think that people have the right to speak out, to express their opinions, to be free,” said Aliaksandra Dubina, a hand-weaver of folk costumes from Brest. She said the rally of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya was the first political demonstration she ever attended.

A widespread movement

The people I met in recent weeks across Belarus name different reasons for their discontent. The government’s bungled response to the coronavirus pandemic, Lukashenko’s ignorance, weakening economy, low salaries, and this general tiredness of the same person ruling the country for decades. But the main takeaway for me is that people see value in, well, democracy. They want their rights to be respected, their votes counted, and their opinions heard.

“It’s not normal that people are scared of being fired and jailed. This is not how things should be done nowadays,” told me Siarhei Malibozhka, a musician who attended Tsikhanouskaya’s rally in Slonim.

“I saw a lot of electoral campaigns in Belarus, and I know how the authorities rig an election. But I am not scared anymore. My salary is 300 Belarusian rubles, why should I be scared?” he said.

This year, widespread and grassroots mobilisation has unfolded to the extent never seen before. It started in March, with some 1,500 volunteers who came to the rescue of Belarus’s healthcare system during the coronavirus pandemic. Civil society was more effective than the state, and many Belarusians will remember it.

For more than two years, Brest residents have been rallying against the construction of a battery plant. Despite detentions and fines, it is perhaps the longest-ever protest in Belarus. In what is usually called citizen participation, a local community united to defend their right to the city.

This summer brought more examples of solidarity, peaceful defiance and self-organisation. When two sound engineers, Kirill Galanov and Vladislav Sokolovsky, were sentenced to ten days in jail for playing the song “I want changes” by Viktor Tsoi at a government concert this Thursday, people collected more than $30,000 for them.

In an attempt to express solidarity with the jailed DJs, motorists self-organised to play the same song on the main streets of Minsk. When the main road was blocked by the police, cyclists joined. Brutal arrests followed.

I remember December 2010, when tens of thousands protesters were dispersed by riot police in Minsk, after the election results were announced. Hundreds were detained, presidential candidates jailed. Many fled the country, fearing repressions. The opposition was left leaderless. The country’s politics seemed deserted. But a few months later, the new wave of protests, the so-called clapping revolution followed, organised by new faces in opposition.

In a suspenseful game of nerves, the people of Belarus played by the rules. President Aleksandr Lukashenko did not. Despite the result of the election, Belarusians have already shown that they want changes, even when the Viktor Tsoi’s song is turned off.