After the USSR collapsed, there was literally nothing in Belarus, but only in terms of material goods. In terms of knowledge, people from the Soviet system and universities were able to create an IT industry, which in 30 years became equal to agriculture regarding its share in GDP. And then, a new political crisis broke out – the most serious in the history of independent Belarus.

How did Belarus enter the 90s – years of chaos after the collapse of the USSR?

“Children, let’s go to the store!” calls Aunt Nadzia, a woman in her thirties. The kids from the neighborhood go with her and disappear over the hill. They enter a large room with granite tiles on the floor and a small queue in the far corner. People are standing in line to buy sugar, which is sold at three kilograms maximum per person.

I stand in the line and stare at the concrete floor of the store. The floor of a large room is paved with huge tiles, and in the corner there is a queue for sugar, which we joined.

I am about four years old, and I did not come here with my mother, but with my neighbour aunt Nadzia. Aunt Nadzia needs to buy some sugar because it’s summer and it’s time to make some jams. But there is not enough sugar: it is sold only at three kilograms per hand, counting children. Therefore, I help her.

It was the situation with goods in Belarus in the early 90s – a shortage and endless queues.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

It’s summer around 1993 when inflation exceeds 1000%. Just two years ago, the empire – the Soviet Union – collapsed, and poverty reigned in its former republics. During these years, engineers and managers with Soviet education created what would be called an IT country three decades later.

At that time, personal computers had just appeared in Belarus. They already ceased to be something intended only for specialists and occupying several rooms.

“Belarus was the assembly shop of the USSR; there were technologies for the manufacture of electronic computers,” says Galina Lades, a professor at the Academy of Arts. “And those people who dealt with them easily switched to personal computers. The electronic computers in machine halls were much more complicated. Hence, people easily figured it out.” Lades began her career in the 70s at the Computing Center of the Institute of Mathematics at the Academy of Sciences in the Soviet Socialist Republic of Belarus.

Computers were not available to everyone, and the cheapest way was to build them from components. And people could do that. The sale and selection of computer hardware and equipment became a business; they were imported from Lithuania, Estonia, and other countries.

In the first half of the 90s, many companies were engaged in hardware, including five to 10 large ones, and there were authorized distributors. One of the first private, local enterprises to enter the computer hardware market was Panorama, already active in 1990. People often also recall a large company called Dainova, which appeared in 1991. The imported IBM it sold could cost about $200. And it was much more than an ordinary person who received a salary of about $10-30 could afford.

One of the giants, the Belhard company, appeared in 1994.

“So that you understand: the then salary in the country was around $10 per month. A laser printer cost $1,200,” recalled Igor Mamonenko, director and founder of the company, in a 2019 interview with onliner, a tech site.

“HP sold us laser printers for $1,000. For us, $10 was good money. Therefore, we counted like this: $1,000 + $10 and we sell it for $1,010,” he said.

Salaries seem small, but no one was surprised if they didn’t get paid for IT at all since there were other benefits. There was a story about how an employee got a job at Sigma-Service, and two months later, someone reminded him that he should receive a salary. And he asked: “Do I also get paid for it?” The reason was that some of the motherboards contained gold, unlike more modern ones, and it was possible to earn good money by writing them off.

A local publishing house, Nestor, also pitched in in the earlier years, says Olga Kiryushkina, ex editor-in-chief from the Nestor publishing house. “The Nestor enterprise has made an active contribution to the development of IT in Belarus. Having existed since May 1991, it was then engaged in the production of computer fonts, with a particular emphasis on the so-called national fonts of the peoples of the almost former USSR.

“Nestor released the first Moldovan, Turkmen, and Belarusian fonts. Also, in 1992, Nestor employees were the first in the former USSR to transfer daily publications from hot [metal] typesetting to computer typing.”

Still, as in Soviet times, a significant part of the sector was made up of state organizations and institutions. If in the USSR they received equipment as part of supplies from the state, now, they bought it from private companies.

State organizations had their projects, in particular, the first and only Belarusian antivirus VirusBlokAda (1997). University students had fun making viruses. According to rumors, for several years in a row viruses swept across Belarus at about the same time as the examination in antivirus protection took place at the Radio Engineering Institute.

In general, specialists from state organizations were slowly moving to private ones. Also, in the mid-90s, outsourced software development appeared.

Computerization and everyday life in the 2000s

People’s way of life gradually changed. It was already possible to receive news not only from the TV; Internet media began to develop; around 2000, a Belarusian email service appeared on the site Tut.by.

Some companies developed websites and sold hosting.

“In 2003, there were about three other hosting companies besides us,” says Margarita Stolzenberg-Semak, who then worked with clients at ActiveCloud.

“It was interesting work; I had to explain to clients what a domain name and hosting are, why they are needed, why they are paid monthly or annually.

“[The large portal] Tut.by was just becoming a news site at that time. It was the time of the forums, and Onliner.by had just appeared. Smartphones were far off, and only a small number of companies had websites. We were already talking about the fact that a corporate website is worth having, but it was still very far from a must-have.”

When hiring, employers requested a new requirement, which sounded like “computer skills.” It meant the ability to turn the machine on and off, enter text, and send emails. Up until 2000, according to Belhard’s estimates, about 400,000 people had learned to work with computers, in a population of almost 10 million.

In the following years, having a computer was still a luxury, but the youth literally besieged computer clubs. The most persistent ones learned to program by hacking games.

“The decline of computer clubs probably began in 2004. You can take the decrease in their number as an indicator of society’s computerization,” says Roman, a project manager. That year, he got his first job in IT.

“At home [people communicated and transmitted data through] local computer networks because the internet was terribly expensive and the dial-up was slow. It could be refilled by purchasing a refill card at a kiosk. Naturally, there was almost zero penetration of mobile access to the network.”

Until high-quality and cheap internet developed, access was organized by bundling through these self-made, illegal local computer networks. Whole communities formed around their creation and support. These networks sometimes later grew into commercial providers.

Passions raged. Keeping a local network server at home was an honorable mission, and one of the Minsk providers was known for literally slicing up illegal home networks with wire cutters.

When laying the networks, one had to be creative, especially if it was necessary to connect two high-rise buildings across a street where a tram ran down the middle. An archer was even invited to one of the Minsk micro-districts to throw the cable, and she did it by shooting an arrow.

Another trend was in the IT industry itself: the era when an IT specialist could program, build a server, and fix an iron was ending. Specializations, instead, emerged: networking and system administration, application programming, security, and so on.

The Emergence of the Hi-Tech Park

By 2005, “the IT industry was doing well and was ready for further growth,” says Gleb Rubanov, an IT consultant.

“There were a lot of outsourcing offices, and the recruitment of specialists there was active, but the requirements for competencies were serious. It was easier to start with no experience at all in companies working for the domestic market. However, graduates of specialized faculties (there were only three of them) usually immediately went to outsourcing. I personally started in 2005 with the 1C company, but a year later, I jumped to EPAM.”

EPAM received foreign investment in the mid-2000s, a boost of capital unusual at the time that allowed it to take off literally. Now it is one of the largest IT companies in the country and provides outsourcing. By 2019, the number of its employees in Belarus had grown to 10,000 people – the size of a small town.

But in the early part of the 21st century, there were almost no product companies that could play on the global market (such as today’s Wargaming, Viber, etc.). Nevertheless, some businesspeople were trying to create an industry organization that would make things easier for everyone.

“Why can’t we create a prototype of Silicon Valley here in the Republic of Belarus, so that people can self-actualize without leaving the country, and if they do, then not buy a one-way ticket?” co-founder Valery Tsapkala recalled a few years ago. In the news recently as a presidential candidate, he was a deputy foreign minister at the time.

“Of course, when I voiced the proposal in the government, they considered me a bit of a dreamer: ‘Do you even understand where you are? How are you even going to create a Silicon Valley here?’” he said.

But Tsapkala’s attempt was successful: in 2005, President Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s special decree created the Hi-Tech Park (HTP), and Tsapkala served as its head from 2005 to 2017.

At first, it was difficult to get into the HTP because the decree severely restricted the profile of eligible companies, preventing, for example, electronics developers from setting up shop there. But gradually, it became easier, and by October 2020, 969 resident companies and about 65,000 employees were registered in the Hi-Tech Park, according to data on the organization’s website). Product development companies are even among them, as the HTP administration emphasizes.

The HTP tax benefits served to reduce the outflow of specialists abroad. Employers were gradually able to pay high salaries and at the same time switch from cash payments in “envelopes” to legal ones without larger tax burdens. It took some time, however, and the “gray” way of doing things persisted for more than a year.

“It’s like drinking beer on the street and smoking inside a cafe or on the stairs at the entrance: until it was eradicated, no one had any questions because everyone has always done this,” a specialist who worked according to this scheme explains.

Startups on the Scene

One of the first product companies in Belarus was founded back in 2004 when everybody was still providing outsourcing: Taucraft and itsTargetprocess project management tool. But in general, before 2010, there was a quantitative growth in the field: money, connections, and knowledge were accumulating.

In parallel, a wave of IT startups swept through many places around the world, and companies that offered their own products and services began to appear in Belarus, as well. In 2012, some in the IT community started saying that “the trend toward a surge of startups has reached Belarus,” as noted on the IT-focused Habr website. In 2016, Tsapkala published a book about IT in Belarus, where he noted a “boom in startups” in the country. And he was far from the only one hoping that startups would transform Belarus’s state-dominated economy into one of innovation.

“I think that if IT is not regulated in Belarus, as it happens in Russia, then this area will continue to develop,” Yuri Melnichek, a well-known IT entrepreneur, venture capitalist, and programmer, said in 2016.

And so it happened. By the end of 2017, Belarus had made fundamental changes including the so-called IT decree (Decree No. 8 “On the Development of the Digital Economy”). Among other things, this document increased the benefits for companies from the HTP and expanded the list of eligible activities in which they could operate.

By 2018, the Belarusian IT sector boasted a large share of outsourcing companies (60.5 percent) with the rest engaged in product development, according to an estimate provided by analyst Alexandra Murphy, writing for the Minsk Dialogue Council on Foreign Relations. She credited the quality of the Soviet education as one of the reasons for the success of the industry. And in the 2019 rating of StartupBlink, which maps startup ecosystems, Belarus placed 55th out of 100 countries (more about the startup ecosystem of Belarus here).

Belarus was one of the first in the world to legalize cryptocurrencies in 2017, and blockchain enthusiasts hoped for a transformation of the economy. “Our rules, which do not exist in most countries, are not a bad step. We just need to wait for the blockchain economy to explode,” said Dmitry Matveev, a partner at Aleinikov & Partners, in 2018.

“With the change in legislation, in particular with the adoption of Decree No. 8, the government gave the green light to the development of a model [for developing products], and conditions for the startups’ development were created in the country,” said Anton Kulichkin, an investor and a member of the Angels Band business angel network in 2019.

By this time, the share of the industry in GDP became comparable to that of agriculture (two years ago, for example, IT accounted for 5.7 percent of Belarus’s GDP, while agriculture and forestry stood only slightly higher at 6.4 percent).

By 2018, in Belarus, there were probably more than a thousand startups at the idea stage, according to business angel Kirill Golub. And by 2020, local investors counted several hundred still at the beginning of the journey but already ready for investment. Among the largest and most famous now are Maps.me, the Viber messenger, the Flo application, and others such as MSQRD, PandaDoc, Kino-mo, FriendlyData, Banuba. Local universities, BSU and BSUIR, produce a flow of IT specialists, said Belhard’s Levin, but disputed the notion that a university education was a requirement to become a good programmer.

“I asked one of the EPAM founders about that 25 years ago, and he answered: ‘We do not need education, but knowledge.’ If a person has managed to learn himself, then, relatively speaking, they [employers] will not take into consideration a lack of knowledge in political science.”

Will It All End Because of Politics?

The natural development of the industry, however, has not gone according to plan.

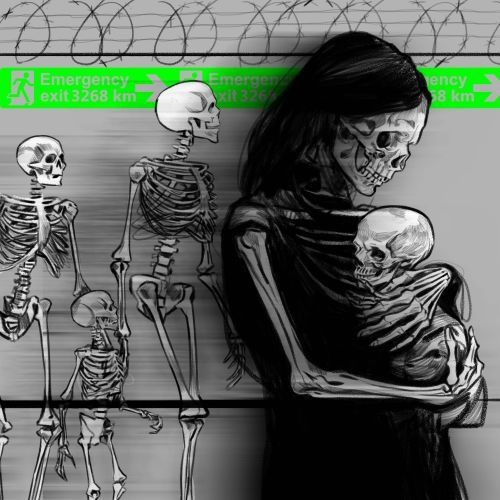

Back in the spring of 2020, here and there, groups of dissatisfied people gathered in anticipation of the fall presidential elections, some signing up to “initiative” groups backing this or that presidential candidate. By the fall, after widespread repression leading up to the vote, they were primed to take on the authorities. On 9 August, Lukashenka claimed a massive victory, and people took to the streets in dozens of cities. Huge protests had never happened in Belarus before, at these sizes and lasting this long. Usually, everything ended in a day or, at most, a month, but they continue today.

The impact on the IT community was immediate – the authorities disconnected the internet for three weekdays after protests broke out.

“Even a week after 9 August, I tried to do something at work, but in reality, instead of producing something, I endlessly explained to clients the plan to compensate for lost production in Belarus or listened to how they demand that all critical or not-so-important functions be taken out of the country,” Maksim Bogretsov, senior vice president of EPAM, wrote in August on his Facebook page.

IT specialists, who had always been considered apolitical, joined the demonstrations, including a rally outside the HTP offices.

According to various estimates, over 30,000 people have been arrested; the number of political prisoners is over 160; and more than 660 criminal cases have been initiated. Some IT companies’ employees returned from prison with serious injuries, saying they had been tortured. Those arrested were sometimes marked with paint in prison, with crosses to indicate they should be beaten harder.

Bogretsov took an indefinite leave from his main job and made the risky move to join the so-called Coordination Council that pledged to oversee the transfer of power from Lukashenka. At the same time, it was already known that council members were imprisoned, and the organization itself was recognized by the official authorities as a threat to their sovereignty.

In August, IT representatives signed two letters calling for an end to the violence. One letter was signed by over 3,000 CEOs, investors, and developers, while the other was signed by prominent IT businesspeople.

One of the top managers of EPAM participated in the development of a platform for alternative vote-counting, the Golos initiative, which made it possible to confirm that the elections were rigged.

IT specialists also created a website to search for detainees and those who had disappeared during the protests. They were tirelessly inventing ways to bring the internet back, as it was turned off every Sunday until mid-December. And they did some initial work on a free offline application called March to monitor the Ministry of Internal Affairs forces at rallies (before stopping when internet service no longer was a problem).

Businesses are trying to play their role: the PandaDoc startup made payments to employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs who resigned and received more than 600 applications in the first month alone. But under pressure and due to arrests of PandaDoc employees, the company stopped. Another startup, however, picked up its initiative. And ISsoft Solutions and Gurtam allocated $500,000 each to help victims during the protests.

During the ongoing protests, you can see anyone on the lists of detainees, including IT executives. In the autumn, a popular joke among IT specialists was: “I ran away from the police on Sunday with one DevOps engineer on Niamiha [a downtown location in Minsk]. Bro, find me! I have a job for you.” And this situation is very easy to imagine.

After issuing decrees to build up the sector and championing the growth of the tech community, Lukashenka hardly expected such a turn, one would assume. And the impact of the economy should be significant.

“If the current state of affairs persists, there is no trust on the part of customers and investors,” Tsapkala, the co-founder of HTP and former presidential candidate, said in September.

Tatiana Marinich, the founder of the BELBIZ group of companies and the Imaguru startup hub, estimated the industry’s daily losses at $100,000 in the fall.

And the official reaction? The HTP reported that everything was fine and new residents had arrived, and the tax authorities said that IT revenues were growing.

Meanwhile, one after another, stories appear about the readiness of IT specialists and their companies to relocate, and the media have reported that dozens of companies are, in fact, leaving.

“We need to get out – this is the mood around IT,” says Stefan Korf, a senior developer from Minsk. “An employee whom we had high hopes for in our company left, and friends are also leaving. Can I count a dozen people? I think so.”