Dismissed as ‘poor thing,’ she gathered the largest rally in a decade. In Belarus, Lukashenko faces a female challenge

The Viasna human rights centre said at least 63,000 supporters of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya turned up for the rally, making it the most massive political demonstration in the past decade and recent Belarusian history.

The rally came as Belarus authorities accused top members of the opposition of collaborating with Russian private military contractors to orchestrate mass riots. Suspects in the case include jailed opposition blogger Siarhei Tsikhanouski, as well as Belarusian opposition politician Mikola Statkevich, who ran for president in 2010.

At the rally in Minsk, thousands demanded the release of all political prisoners. Presidential candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya dismissed the alleged mass riot plot as nonsense.

the magazine

By clicking „Sign up”, I give permission to receive newsletter Unblock sent by Outriders Sp. not-for-profit Sp. z o.o. and accept rules.

“My God, what revolution? We are peaceful people, and we want peaceful changes in our country. Why are the Belarusian authorities provoking their people?” she said at the rally, as the crowd chanted “Freedom!” and “We want change!”

“These rallies give me hope that change is possible,” says Vladislav Karapuzov, 22, who came to support Tsikhanouskaya, even though he initially wanted to vote for Valery Tsepkalo. He says that he is dissatisfied with Lukashenko’s “disrespectful attitude towards people and the state structure that is associated with only one person.”

Tsikhanouskaya pledged to free political prisoners, reverse authoritarian changes to the constitution made in 1996, and to run new, free elections within six months. Initially a stand-in for her husband, she joined forces with female representatives of Lukashenko’s other strongest rivals, former banker Viktar Babariko, currently in jail, and a former ambassador to the United States Valery Tsepkalo, founder of a high-tech business park, who was denied registration.

The three women – Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Maryia Kalesnikava and Veranika Tsepkalo – have been touring the country, gathering unprecedented crowds of supporters in every city and town they visit. Despite remote locations on the outskirts, thousands arrive to cheer the united opposition trio. People wave flags and balloons emblazoned with the opposition’s campaign symbols – a victory sign, a clenched fist, and a heart.

At the rally in Minsk, the three women brought stories from their personal lives to express their anger with the Belarusian government and Lukashenko.

Veranika Tsepkalo, the wife of Valery Tsepkalo, said that she “saw the real face of these authorities many years ago,” when her mother was detained in hospital, despite being diagnosed with cancer. She also reminded that her husband has fled to Moscow with their two children fearing he would be arrested and stripped of parental rights. She cried during her speech.

The crowds responded with the slogan “Shame!”

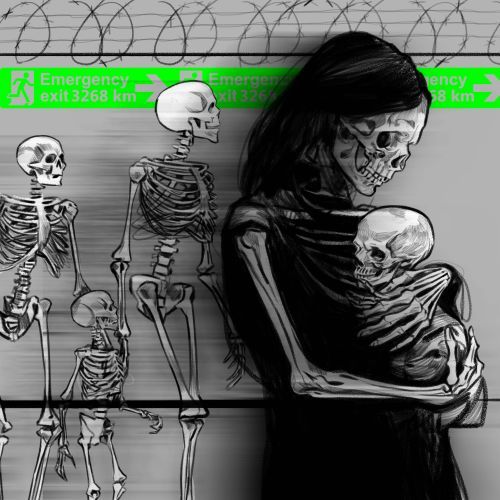

Tsikhanouskaya herself had to hide her two children in “one of the European countries” after she received anonymous threats that they would be taken away if she didn’t stop campaigning.

“Poor thing” as the main rival

It’s not only their personal stories that draw thousands to their rallies.

In the past weeks, Tsikhanouskaya’s rhetoric has become sharper and more critical.

In her speeches to crowds at rallies and her national television addresses, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya directly blames Lukashenko for poverty and mismanagement. Although she uses the elusive authorities, it is rather clear who she referred to.

She talks about independence as a priority and promises that Belarus will no longer be poor. Her image and words are all about offering a positive agenda. It is quite a difference compared to Lukashenko’s campaigning style, as he is constantly visiting military bases and talks about harvesting.

Having become the new face in Belarusian politics, Tsikhanouskaya managed to unite various groups of people: supporters of the three main male candidates, who were barred from running in the election; members of the traditional opposition groups; and those who never attended political protests before, but they feel they want change now.

Viktar Bulychau, 28, says he never saw “anything like this” in Viciebsk, a city of 360,000 people in northeast Belarus, not far from the Russian border. Last week, some 8,000 people participated in what he calls “one of the largest political protests” in his hometown. Initially a Babariko’s supporter, Bulychau says he will vote for Tsikhanouskaya in this election since his candidate was banned from the ballot and jailed.

“Lukashenko is not a good manager, and Belarus is poorly governed,” he says. “I have to work as a truck driver with a Lithuanian company because there are no well-paid jobs in my city. Why?”

Across the country, people are increasingly seeing the value in free and fair elections and the change of president.

“Even if this change would be for worse, I want to choose myself, and my vote is respected,” says Julia, 38, from Barysau, where up to 5,000 people showed up last week for a rally of Tsikhanouskaya. She asked not to give her last name, since she is afraid of being fired.

Tsikhanouskaya keeps repeating that she is not a politician and her main goal is to organise a new election with “strong candidates” who are now jailed. But at a rally in Homiel, when she joked that she simply wants to keep frying her cutlets, someone asked from the crowd, “Could you stay as president? It won’t be fair if you immediately leave the job.”

A female president “would collapse, poor thing,” Lukashenko recently said. The country, he added, “has not matured enough” to vote for a woman. And yet surprisingly, a stay-at-home mother-of-two has become his main rival. Dozens of thousands chanted her name at the rally in Minsk and across the country.

“At first, she was an ordinary housewife, but I think she might become a good politician,” says Elena Pavlovich, 32, an owner of a print shop in Barysau. She and her friends brought three portraits of the united trio and gave it to Tsikhanouskaya during the rally. “We wanted to support her as a woman, who is ready to sacrifice her old life for the sake of the country,” Pavlovich says.

A former member of Babariko’s initiative team, she will also vote for Tsikhanouskaya in the election next month. For Pavlovich, Lukashenko’s out-of-touch and “disrespectful” attitude on female leadership became the last straw.

Russian plot in Belarus

Right ahead of the massive rally in the Belarusian capital, the authorities have accused 33 Russian militants detained near Minsk of preparing a terrorist attack. Belarus state TV channels reported that the men are members of the Russian private military company Wagner, which has been tied to an ally of Vladimir Putin and has fought in armed conflict in Ukraine, Syria and countries in Africa.

The head of the country’s security council, Andrei Raukou, said investigators suspected as many as 200 Russian combatants had entered the country, with another two groups being allegedly formed outside the Russian cities of Pskov and Nevel. “We are searching for them,” said Raukou. “But it’s like a needle in a haystack.”

However, local human rights defenders raised concerns that a Russian alleged terrorist plot might be used to justify the further crackdown on the opposition. Since May, more than 1,000 people have been detained for taking part in protests across the country.

After the detention of Russian militants, the authorities said security measures would be increased at pre-election rallies. Tsikhanouskaya is the only candidate who gathers massive crowds. Some believed it might prevent her from further campaigning.

Lukashenko appears to be preparing for the likelihood of the protests that might follow his re-election as president. Minsk residents have recently had a rare opportunity to see BTRs, armoured personnel carriers, floating down the river. In the past two weeks, Lukashenko personally inspected several military brigades across the country. He again reminded the country’s armed forces that “modern wars are triggered by street protests”. While talking to the military unit of the internal troops in Minsk, he pledged to support the army. The video of the riot police training to disperse protests was aired on state TV.

“We will bring everyone to their senses when and where it is necessary. There will be no coups in the country. Or Maidan-like revolutions,” he promised earlier in June.

Tsikhanouskaya addressed the military at her latest rally in Minsk as well. “Belarusians who want a decent life are not criminals. Please do not go against your conscience, do not go against your people!” she said.

Belarusians have responded with solidarity and self-organisation to both threats and ineffectiveness of the government. They’ve collected more than $160,000 to pay off the fines imposed on those detained in recent months. They formed human chains of solidarity in nearly 20 cities across the country when Lukashenko’s most serious political opponent Viktar Babariko was arrested.

“People can’t get rid of this feeling of injustice, a feeling of struggle. It is inside them. They simply needed a trigger,” says Siamion Bukin, who came to support Siarhei Tsikhanouski during his recent trial on Monday.

Bukin is a Cirque du Soleil performer who came back to Belarus from Canada and the US because of the pandemic. He says that if “everything goes well” during the election, he wants to stay in Belarus.