Being a Trans Person in Iran, an Overlooked and Misunderstood Minority

Words and Photography by Fatimah Hossaini

Edited by Sharif Safi

In 1986, Sayeed Rohullah Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader, issued a fatwa, a religious edict, allowing a transgender woman, Mariam Khatoon Malek Araa, to have the first legally-sanctioned sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in the Islamic Republic.

“That fatwa built a legal basis for other transgender people and paved the way for them to undergo SRS … It was a huge breakthrough that allows transgender people in Iran to reassign their sex under the umbrella of law and Islamic jurisprudence,” claims Muhammad Mehdi Karimi Niya, a religious scholar who has written about the issue of transgender people and Islam extensively.

Though Khomeini’s edict has allowed for hundreds of transgender people to undergo SRS at relatively low costs, the overall situation for transgender people in Iran has not seen much improvement over the last 35 years.

Behnam Ohadi, a psychologist and sexologist, says that in recent years, even the words of Khomeini have not been enough to quell the criticisms and opposition of sex reassignment surgeries.

“There are several movements formed against transgender people… They believe that when Imam Khomeini issued the fatwa, he had been influenced by the psychologists who had conspired to get him to make the declaration.”

Adding to the misconceptions and stigmas against SRS is that in Iran many lesbian and gay people are encouraged to get SRS rather than let them live as a homosexual based on their biological sex. It has both caused the number of SRS procedures to skyrocket and reinforced the discrimination against transgender people.

Despite the difficulties, thousands of transgender people across Iran are pushing ahead and trying to live their life.

Saman Nikpey (“Saba”) was born in 1994, in Tehran. He is a trans man who has fought a wide range of social taboos and barriers in his life.

“I was in secondary school when I started noticing that I am different from other girls. My feelings, behaviours and interests were different from the rest of the girls around me. Gradually, I started noticing that men don’t attract me, and I was more interested in girls. I didn’t know and couldn’t understand why I feel this way.”

He adds that he couldn’t share his feelings with anyone; neither at his school nor with his family.

“I couldn’t share it at my school, because I was afraid they would kick me out. Despite having an educated family, I couldn’t dare to talk to my parents for years. I had to keep my feelings to myself. It was eating away at me,” he adds.

Saman hid his gender and didn’t talk about his feelings for years. During his second year of undergraduate study, he decided to be honest with himself and started researching and reading about gender identity online.

“I couldn’t bear it anymore. I wanted to know whether I am a girl, a boy, or a gay.”

He adds, “after weeks of reading, I finally found out that I am transgender. When I learned about sex reassignment surgery (SRS), I was so happy. I immediately talked about it with my parents. My parents strongly objected. It took me four years of insisting on convincing them to at least take me to a medical counsellor. Whatever the counsellor would say about my gender, I would accept.”

In their very first session, the counsellor confirmed that he was indeed a transgender person. His father leaves the counsellor’s office with anger and still doesn’t approve of the SRS.

After a few more years of insisting, Saman convinces his parents and gets his SRS approval from a medical professional. “It broke my parents, but it was what I wanted. I had to do it.”

The next step is to finish the very long official paperwork to get approval for the surgery. Saman’s SRS has to move up through the courts so that a judge can come to a decision. The judge then asks for confirmation of the legal, medical commission, ending with the court’s official approval.

“After 27 years, finally, I could overcome all the challenges, and now I am waiting to go under surgery in a few months. SRS contains many surgeries, but to renew my documents and identity card, two surgeries are compulsory at this stage: chest masculinization and hysterectomy.

The most difficult surgery among all is the scrotoplasty and metoidioplasty, which take a lot of time and are expensive. In Iran, only a few public hospitals cover the costs of such surgeries with insurance. Otherwise, people have to personally pay for such kinds of surgeries which cost a fortune.”

Saman says that such surgeries aren’t compulsory in other countries to get your new documents and IDs. He insists that he doesn’t want to get the surgery to get his new documents. He is doing it because he wants to have a more masculine body finally.

Saman now injects testosterone to grow a beard and voice masculinization. He is yet to undergo the hysterectomy. The injections have increased the density of his blood and weakened his body.

“Luckily, I have good parents who now support me. There have been parents who have killed their children rather than agreeing to an SRS.”

“I have a girlfriend now. Also, emotionally I feel so better now,” Saman says.

“However, when I walk on the streets with my girlfriend, sometimes people harass me because I am still physically weaker than other men,” he continues. “Here, the law won’t approve SRS for anyone under the age of 20, because they think anyone younger than that age isn’t adult enough. However, I believe that this age should be lowered to 13 or 14 because it’s the age that a person can reach sexual maturity.”

Maral Muhammadi (“Arash”), was born in 1997, in Ahwaz, Iran. Four years ago, she moved to Tehran.

When Maral was in school, she used to have girlish behaviour and loved to wear female clothing despite being a male by birth. The other students would bully her because of her different interests and feminine behaviour.

” At night, I would put makeup on me and dress like the other little girls. My father would punish me, telling me to behave like a man. I didn’t know how to explain to him that inside I am a girl. I am not a man.”

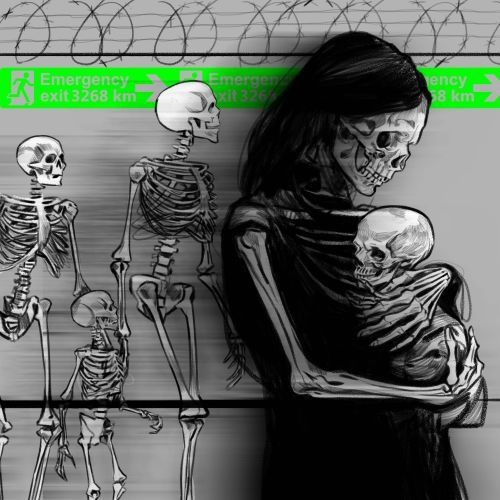

Maral now lives with her aunt – after being evicted from her home years back. She tells about her challenges finding a job and working as a transgender person. “I am now working as a telephone operator in a local restaurant. I could get this job because it doesn’t require me to be visible to the customers and the public – it is very difficult to get another job than this if you are a trans. Plus, transgender people are so underpaid by their employers.”

Maral says that she didn’t have feelings for girls since adulthood, and she could find the boys more attractive, despite being a male by birth. “Because of being a transgender person now, whenever I enter any relationship with boys, it doesn’t last long. After some time, when I get attached to them, they leave me. It breaks my heart. It’s obvious they don’t like me because I am a transwoman.”

Maral so severely wants to go under sex reassignment surgery to feel her real gender identity, but she says she doesn’t have the money. None of her friends or family is willing to support her.

“I am troubled by both the police and the public. I have been put behind bars many times. The police ask why I wear women’s clothing when I am a man. Other times they ask why I don’t wear a hijab if I am a girl? I’m stuck in a situation where I don’t know whether to play a girl or a boy in society. People here don’t have an exact definition of what it means to be transgender. When I walk on the streets, people would harass me and film me. It is the story of my everyday life.”

Maral says she doesn’t have anywhere to go when she feels like spending time outside. There is only one park in Tehran that transgender people can go to safely. Some transgender people go there to make some money through prostitution out of desperation.

“It is really hard for trans people to find jobs. They see prostitution as a way to make money. I can’t live such a lifestyle though. I am fortunate to have found a job that pays $70 per month, and I am quite happy with it.”

Omid Arta Banaee (“Mahdees”) was born in Tehran in 1994. Omid used to wear men’s clothing since childhood. He loved to play football and other games with boys. Omid didn’t show much interest in the games other girls in their neighbourhood played.

“I didn’t know why I had to act like a girl when inside I felt like a boy. I even prayed at night with the hope that when I wake up tomorrow, my genitals are changed, and I am no longer a girl.”

By the time he starts to grow breasts at 13, Omid’s frustration grows. He had always imagined himself to have a masculine body, and yet his breasts betrayed that image.

Omid went so far as to bound his breasts. In his last year of school, Omid moves in with his grandmother to study in a private school. At this point he cannot hide his desire to be a man any longer. His behaviour starts to draw the attention of the school. Eventually, his teachers place a separate chair for him to distance him from the girls in the class.

The school eventually sets a rule for Omid, forbidding him from talking to the girls because he doesn’t act and behave like the other girls. When he graduates, the school introduces Omid to a psychologist.

“I initially couldn’t express myself clearly to the psychologist, but later I decided to talk frankly about my feelings. I told him that I like girls and that I’ve never been attracted to the boys.”

The doctor asks Omid if he knows what transgender people are, Omid says no. The doctor goes on to reassure Omid that there are surgeries for people like him.

“When I read about it, I was so happy that I am not alone with this feeling and most importantly, there is a solution.”

The doctor tells Omid that he will have a difficult journey in Iran, and advises him to head to another country that would accept transgender people.

When Omid assesses his situation, he decides to move to Yokohama, Japan.He already had a basic understanding of Japanese, and his uncle lived in Japan.

Omid only lasts four months in Japan due to the difficulties of that country and because he was admitted to a well-known university in Iran. Looking back on that decision, Omid says he wishes he had come back to Iran.

Omid attends the university donning a masculine appearance. It only leads to more harassment. “After a year, I had to withdraw. I couldn’t bear the harassment.”

Even with all these hardships, Omid still couldn’t bring himself to get the SRS. He says he was still confused and feared that it could all be an “illusion.”

But all that changed during his sister’s wedding when his mother forced him to go to a beauty salon, get made up and put on a dress and high heels.

“When I looked at myself in the mirror, I hated myself. It was a strange and difficult feeling. I cried so much that I ruined my makeup. That was when I realized that it’s not an illusion; I am not a girl.”

After that, Omid has a frank conversation with his family, telling them not to insist that he continue to dress as a female. His parents resist and threaten him with eviction.

“My father and brother had businesses and could help me with the expenses of my surgery, but they told me that now if I am a man, I should go out and make money myself for my surgery”.

Realizing his family wouldn’t support him, Omid took on odd jobs at metro stations and factories to help finance his SRS. Even after he managed to save up the money, Omid’s parents remained obstinate.

“They kept telling me that it’s fine for us if you wear menswear, but do not have the surgery.”

It was then that Omid fell in love with a supportive woman who saw him through all of his tough times with his family and even several suicide attempts.

That relationship becomes the catalyst for Omid to get the surgery. He wants to be with the woman he loves without complication.

It took two suicide attempts for his mother to convince Omid’s father to let him get the SRS. He had his hysterectomy in April 2017. Three months later, Omid also successfully undergoes his chest masculinization surgery.

Omid adds, “It was legally easier to do SRS until 2019, but after that, the government has put a lot of other paperwork in the process which makes it harder than before. Now, I have got all my new documents with my new name and identity as Omid Arta Banaee, and I am currently working in a store – having no more problems. However, being a transgender person here is never easy.”

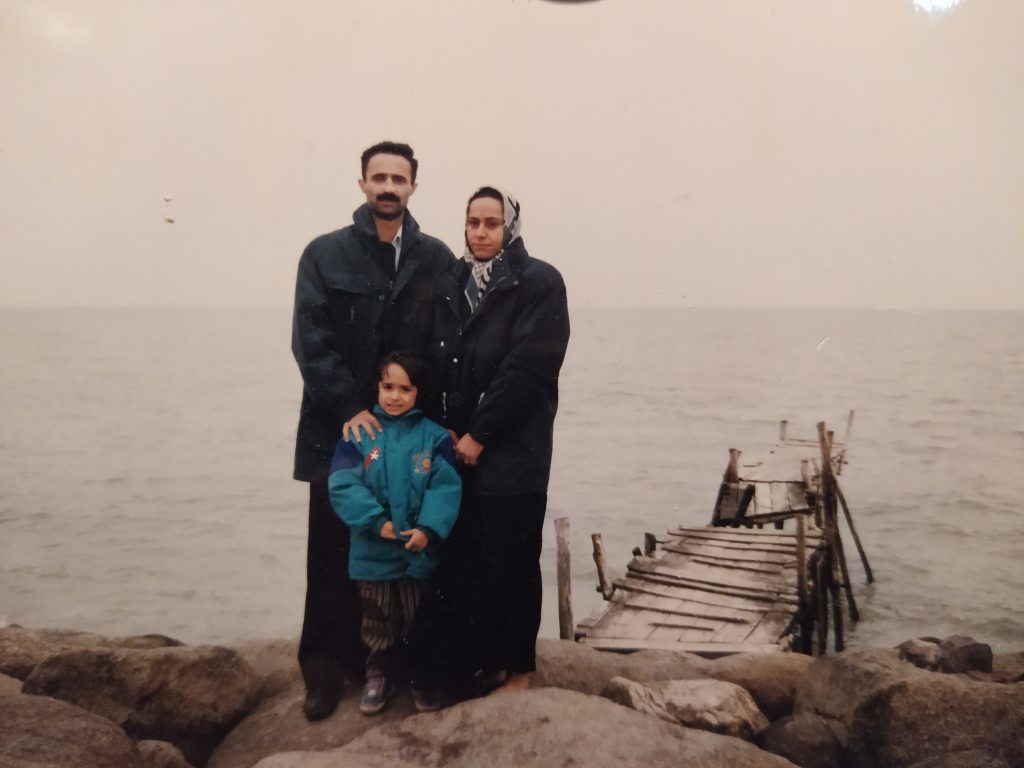

Muhammad Ali Taher Khani was born in 1975 in Tehran. By the time he was eight-years-old, Muhammad Ali already knew he was different from the girls who were his age.

“I always loved to play with boys despite being a girl. Even in our childish games, I used to play the role of a boy or a father. I loved to wear menswear, and used to speak like boys which frustrated my parents. When I gradually grew up, my sexual desires started annoying me. After years of struggle and separation from my family, the medical counsellor confirmed that I am a transgender at the age of 19. Back then, it was much harder to get the SRS approval from officials. After almost seven years, I received the approval to go under SRS. However, because of my breakup with my girlfriend, I caught depression, and I got into drugs. It took me another five years to recover and overcome drug addiction. Finally, when I was 31, I did hysterectomy as the first surgery of SRS.”

The expenses of Muhammad Ali’s surgery were covered by Imam Khomeini Hospital, a state-owned hospital, which was named after the supreme leader, Imam Khomeini, because Ali proposed the hospital to introduce four transgender people. The hospital could use their ovaries in their laboratories, but the doctors should perform their surgeries for free in return. Ali says it’s the least he could do for his fellow transgender people. When Muhammad Ali was 33, he did his mastectomy surgery after his first marriage with another transgender person.

Eight years ago, Muhammad Ali joined Mrs Mariam Khatoon Malek Araa’s association – precisely one year before Malek Araa’s demise.

“Mrs. Malek Araa had registered the Gender Identity Disorder Association in 1996, nearly ten years after Imam Khomeini issued a fatwa in 1986 – legalizing the sex reassignment surgery. She was the first person to have received the approval of sex reassignment surgery after the Iranian revolution. Before Mrs Malek Araa’s demise, she put me in charge of the association. After forming the board of directors – all of them transgender people – I officially took on the job as the association’s CEO. When I became in charge of the association, I changed its name from “Gender Identity Disorder” to the “Gender Identity Dysphoria.”

Muhammad Ali and his colleagues continue their activities in the building of municipality while back then the traffic and presence of transgender people there were very controversial. They started carrying out several initiatives, organizing different classes, cultural events and therapy sessions.

“We tried to provide any support and information for the transgender people in Iran through this association. However, after a while, we faced many challenges, mainly because of people and neighbours’ complaints about the lack of budget. Gradually, our members started losing their trust in the association. All these obstacles made us close the association, and I left it too four years ago because it even created so many challenges in my personal life. In Iran, sex reassignment surgery has been accentuated, but the life of transgender people post-surgery has been overlooked. Transgender people are hardly integrated into society, and they have no job, identity or social security.”

Muhammad Ali says that it’s essential for transgender people that they should prove themselves to society and use their capabilities at the first stages. They also should gain the support of their families because families do not have sufficient knowledge about transgender people in families and it causes a lot of problems. “The national media and other organizations working for protection and support of transgenders play an important role in social acceptance and integration of the transgenders into society. From time to time, there are suicide cases. False diagnosis, forcing homosexuals to go under sex reassignment surgery and gender inequality are a few reasons for the suicide cases in Iran.”